Bronisław Piłsudski — the Marshall's brother and a pioneer of ethnography

Józef Piłsudski was the well-known politician and military leader, who made an enormous contribution to the restoration of Poland's independence. So it might seem strange that his grandnephew, and the last male descendant of this family line, should be … Japanese. That happened because of Józef’s older brother Bronisław, whose biography could be a scenario of many a film.

On his way to penal colony

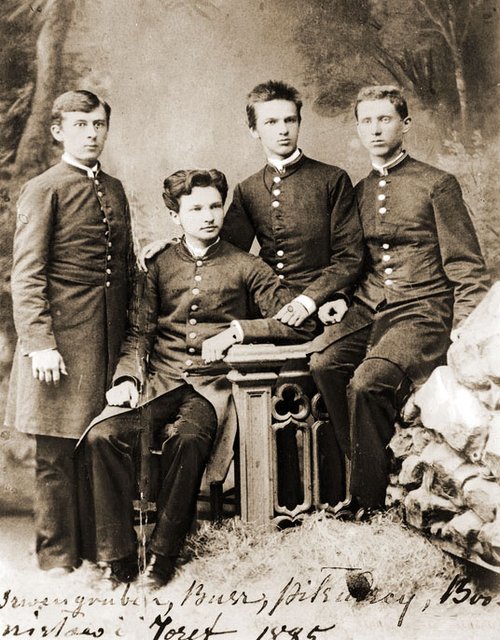

Bronisław Piłsudski was born on 2 November 1866 into a Polish noble family living in the Vilnius region, which at the time was part of the Russian Empire. After his mother's death, he left for Petersburg and continued his education at university. It was there that an incident took place that would change his life for ever. Even though his role in the assassination attempt on the Tsar Alexander III has not been fully explained until today, he was sentenced to death, at age 21, for his part in the conspiracy. After pardon, the sentence was commuted to 15 years of penal servitude on Sakhalin, a Russian island on the Pacific Ocean, seven thousand kilometres from home.

At the beginning of his term he used to clear the forest and work as a carpenter, but later on his education earned him lighter duties like working at a prison office or teaching Russian. In this period he developed an interest in the local tribes and their cultures, as well as publishing works on meteorology. After ten years he was released from serving the remaining sentence but with an order to settle down in the Russian Far East, which was standard practice towards exiles in tsarist Russia.

Ainu — research passion followed by love

Ainu — research passion followed by love

At first, Bronisław worked at the Vladivostok Museum, was a secretary of the Russian Geographic Society, and prepared an ethnographic exhibition at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900. But after some time, he returned to Sakhalin. Because of his ethnographic activities, he received a commission from the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences to explore the cultures of the Gilak, Orok, and Ainu, with whom he developed deeply personal ties. It was in the house of an Ainu chief that he met his future wife, Shinhinchou, who taught him the language of her people. The wedding came one year later, and the ceremony differed from European ideas and traditions, to say the least. All that Bronisław had to do was just look at the bride and then sit down to dinner with her. It was not only Shinhinchou's dress that did not resemble anything of the contemporary Western image of the bride — in line with local beauty ideals her body, including face, was covered with numerous tattoos.

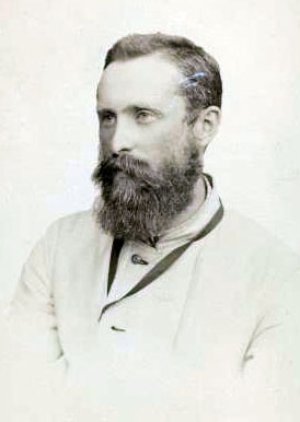

Bronisław Piłsudski did not treat the Ainu as a strange research object. He became one of their own and took to documenting the tribe's language and customs. He also tried to share his knowledge with them: he taught Ainu people how to work the land and salt fish and, later, arranged primary schools and vaccinations. He supported the tribe's cause in official matters, over time earning the nickname "the king of Ainu." In the course of his research, he developed extensive written documentation, took well over 300 photographs, and compiled a dictionary with ten thousand words from the Ainu language. Using Edison's phonograph, he recorded their tales, songs and prayers on wax and tin cylinders. He had two children with his wife: son Sukezo and daughter Kyo, the latter of whom Piłsudski never saw. In 1906, after 19 years in the Far East, he embarked on a journey from Japan to his native Polish lands.

Europe — a home not so sweet

He settled down in what is today southern Poland, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Prussian rule). However, embittered by the unenthusiastic responses to his work, he left for Vienna, then Switzerland, after the outbreak of the First World War. He joined the Polish National Committee organised by Roman Dmowski. In 1917, he moved to Paris, where, on 17 May 1918, half a year before Poland regained its independence, he drowned in the Seine. According to the French police it was a suicide.

Ironically, the return home from the Far East proved difficult and disappointing for Bronisław. Besides zero interest in his work, he also struggled with the lack of money to support himself. In spite of the wealth of experience as an ethnographer, he was refused jobs at universities when it turned out he had no degree. On top of that, the surviving notes reveal that Bronisław Piłsudski was suffering from depression and, in his late years, various types of mania. Allegedly, he would intrude on his neighbours in Paris at night and say he had to do something to save the Ainu from persecution. Even though he was profoundly attached to their culture and was enduring financial difficulties, he did not make up his mind to return to the Far East, in spite of receiving such a proposal from Russian researchers.

Ironically, the return home from the Far East proved difficult and disappointing for Bronisław. Besides zero interest in his work, he also struggled with the lack of money to support himself. In spite of the wealth of experience as an ethnographer, he was refused jobs at universities when it turned out he had no degree. On top of that, the surviving notes reveal that Bronisław Piłsudski was suffering from depression and, in his late years, various types of mania. Allegedly, he would intrude on his neighbours in Paris at night and say he had to do something to save the Ainu from persecution. Even though he was profoundly attached to their culture and was enduring financial difficulties, he did not make up his mind to return to the Far East, in spite of receiving such a proposal from Russian researchers.

Overshadowed by his brother

A man of an entirely different disposition than his brother Józef, Bronisław was introvert, focused, and not sharing the flair for all things military. In a letter from exile to his family, he wrote that he had to resign himself to his fate, while “Józef is destined for greater things” (Józef Piłsudski was also serving an exile sentence, but without penal servitude and in much “closer” Siberia). Also after his death he was forgotten. In the interwar period, his achievements were outshone by his brother Józef's statesman status, while after WWII, paradoxically, it was exactly why his name was blacklisted — communist authorities loathed everything that resembled the Second Polish Republic. Bronisław Piłsudski was rediscovered because of his recordings of the Ainu language. Admittedly, they were found as early as 1930 in his house in Zakopane, but back then they were unreadable. It was only in 1982 that Sapporo University was able to play them back using a laser technology. This discovery ushered in a renaissance of interest in the life and work of Bronisław Piłsudski. Research papers, films, and radio broadcasts about him followed. The city of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk and Hokkaido island have monuments to the famous ethnologist, while Poland has commemorated him with a postage stamp and a coin.

Japanese epilogue

Japanese epilogue

As befits a colourful biography, Bronisław Piłsudski's life story has an unusual epilogue. Kazuyoshi Kimura of Japan learnt only in his adult years that he is one-fourth Ainu and one-fourth Polish, which must have surprised him even more. He is Bronisław Piłsudski's grandson, i.e. Józef Piłsudski's grandnephew, and, even though he has a different surname, he really is the last male descendant of this family line. He was unaware of his roots because the Ainu were persecuted by the Japanese state from the late 19th c. over the following several dozen years. Although an ethnic minority estimated today at at least 24,000, they were not officially recognised in the 1950s. Mr Kimura's grandmother and father hid the truth about their family's roots from him for his own good. As regards the surname, Bronisław Piłsudski's widow and children did not take it because the Ainu just did not use surnames. The family were given the surname Kimura after being resettled to Hokkaido island. It was also belatedly that Józef Piłsudski's descendants learnt about their Japanese relatives but managed to get in touch with them years later.

Nowadays, efforts by the Ainu and materials collected by Bronisław Piłsudski have revived the memory of their customs and an act on protecting and promoting Ainu culture came into force in 1997. Ainu culture is featured on an exhibition, among others, at the Shiraoi Museum on Hokkaido.

Exhibitions about Bronisław Piłsudski and the Ainu currently on in Poland:

- 19.05.2018-11.11.2018 The World of Ainu. From the Time of Bronisław Piłsudski to Shigeru Kayano (Municipal Museum in Zory)

- 18.10.2018-20.01.2019 The Ainu, the Górals and Bronisław Piłsudski (The Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology, Krakow)

29.10.2018