Bohdan Butenko: I am indirectly a pupil of Matejko and Mehoffer

I cannot do everything I like but I also cannot do something that I do not like. That's a big difference. I have made some compromises in my life, but it also depends on what we call a compromise - because if it’s about changing the format or font, then yes, it used to happen,” says the cartoonist Bohdan Butenko.

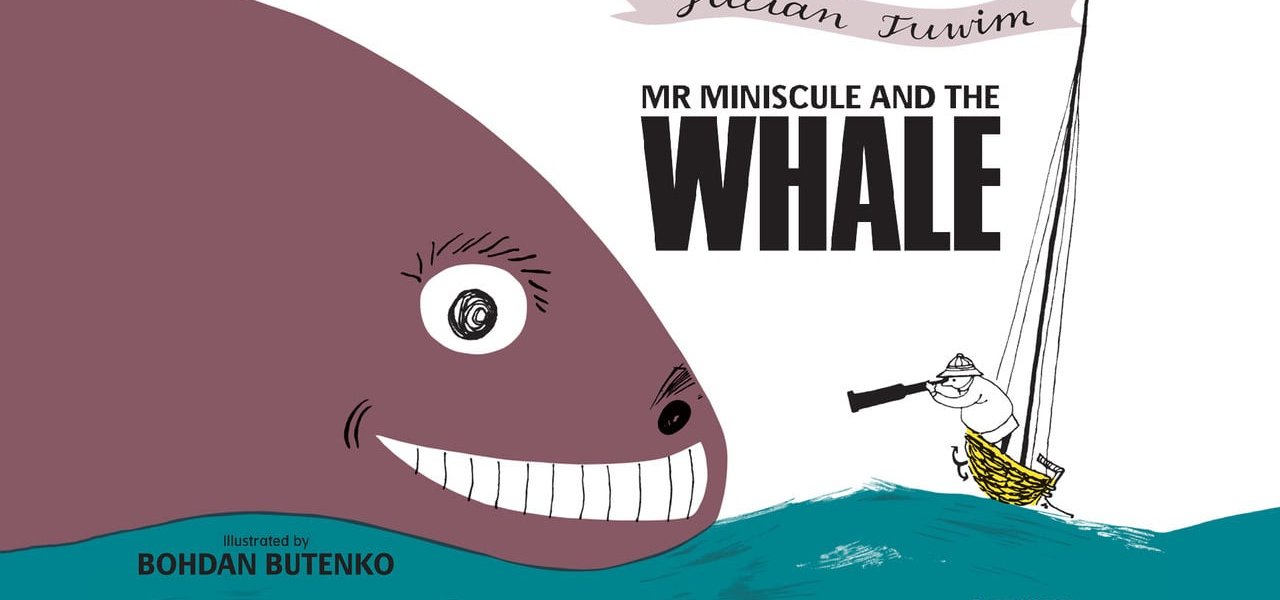

"Rzeczpospolita": During the British royal couple’s recent visit to Poland, their children received as a gift a book titled Mr Miniscule & the Whale by Julian Tuwim, illustrated by you. Were you happy?

"Rzeczpospolita": During the British royal couple’s recent visit to Poland, their children received as a gift a book titled Mr Miniscule & the Whale by Julian Tuwim, illustrated by you. Were you happy?

Bohdan Butenko: It was definitely nice. This book was my debut, so I am all the more pleased that people still appreciate it. It is known not only in Poland; it has been translated into several languages. Classics are still going strong.

You were a pupil of Jan Marcin Szancer, a famous illustrator of books for children and adults. Is it a burden or a privilege?

I think it is a privilege. I was lucky to meet him and to be his student, and then to graduate under his direction.

From an artistic point of view, it was a meeting of two different worlds – his subtle, delicate strokes and your black, thick lines.

I have said time and again – and it is still true – that I'm indirectly a pupil of Jan Matejko. Among Matejko’s pupils was Mehoffer, among Mehoffer’s – Szancer. I was a pupil of the latter. Could we say of any of them that he and his master were alike?

But we do not know whether their artistic relationships were easy...

Certainly not always. But when it comes to Szancer, he was an excellent professor in every respect, not only a man in his own right but also a thorough teacher who would encourage students to remain who they are, to explore and develop their own path. It was not so obvious; generally speaking, it is easier for a lecturer when students follow his way of thinking. At Szancer’s workshops some students were prone to follow the artist’s lead. But he was very kind and tried to encourage them to explore on their own. He would never cool their zest, just the opposite – he was always very supportive. When I told him that I also wanted to be a student of Professor Henryk Tomaszewski, he said "go ahead, but just make sure you do not drop out of my classes." And at that time, Tomaszewski was assisted by Jan Lenica.

Did they influence you a lot?

They certainly did. One of my professors - but it was not Szancer - told us repeatedly that at school we should learn as much as we could and devote as much time as possible to studying. And then he would add, “but once you leave school, try to forget it as soon as possible.”

However, when looking at your work, Szancer must have understood that you would have trouble getting a diploma in the 1950s - a difficult time in Poland, when, according to the Socialist Realism doctrine, art had to reflect what was plainly visible and real.

Szancer understood more than that. It was 1955, a year which saw the World Festival of Youth and Students and a very important exhibition at the Arsenal. Though hardly remembered today, it was a sensation in those times, a turning point. When I was not allowed to present my diploma work in February 1955, the professor told me not to worry and to keep going. To be honest - I had not expected my work to be rejected, although the character of my drawings did depart from what was then the official line. But Szancer's attitude to me did not change. I kept coming to him and he would make corrections to my work, although formally I was no longer a student. It is quite remarkable that in June of the same year, after the political breakthrough, the same work – but now finished – received full marks from the very same professors who had previously rejected it.

But you probably felt compensated as a result of the very interesting job you took up immediately after graduating – the artistic editor of Nasza Księgarnia Publishing House. It must have been a distinction for such a young person.

It was partly a lucky coincidence. I had been noticed at the diploma work exhibition. And it must be added that my works were displayed in a special way – they did not hang on the walls like the others, but were arranged on a long table in the middle of the room. This is also curious. But before everything went so well, there were some technical issues. There was a custom that every student would bring his or her diploma work to the dean's office and try to make it look elegant. I wasn’t able to buy any Bristol board for my diploma work folder, as it was quite complicated to get materials for work back then. After a friend of mine finally helped me out with a piece of cardboard, I spent several days polishing the folder. It was beautiful. Then I went to the dean’s office to remove my works from the ordinary grey envelope I initially used and put them instead in the folder. But it turned out that the examination board was already debating. Although they had to take my works out of a grey envelope to look at them, eventually it all ended well for me as I avoided the stressful waiting for the result.

Not only the Bristol board was difficult to come by, but other materials too. Is this the reason why you painted only in black ink?

You are right, it wasn’t easy to get the materials needed in my profession. And that's why I was economical with my technique. But as soon as colour was available, I was happy to enrich my characters with it. For example Gapiszon (‘Scatterbrain‘) was initially black and white, but as soon as I was able to use colours in the “Miś” children’s magazine, I gladly took advantage of it.

“Miś”, “Świerszczyk”, and “Płomyczek” were magazines filled with your characters, shaping the imagination of several generations of children. Was it more about fun or deliberate education?

“Miś”, “Świerszczyk”, and “Płomyczek” were magazines filled with your characters, shaping the imagination of several generations of children. Was it more about fun or deliberate education?

The former was naturally connected with the latter. And to this day “Świerszczyk” has retained much of its graphic flair. I cannot comment on the texts and literature. It's not my specialty.

But you too write stories you later illustrate.

Here I would like to invoke the excellent French painter Georges Braque, who used to say that if he wanted to have a painting, he simply painted it. It is the same with me – when I have an idea for an illustration, but I lack the text, then I write it (myself).

For yourself or for children?

I need to write it for myself to be able to write for children. Sometimes I debunk fairy tales for children, as was the case with Snow White, which consists of four variations on some well-known fairy tales. This year Wesoły kaszkiecik (‘Merry Flat Cap’) was published, whose main character, the carefree Dyzio, tries to find the owner of a cap he found in the bushes, embarrassing the people he meets along the way.

After 1956 political tensions in Poland eased, but as an artistic editor of a publishing house, you may have encountered some trouble with publishing books by certain authors. Did censorship interfere in children's literature?

Of course. At times it was very painful. I worked many times with Wiktor Woroszylski, the author of the poetic anthology Nastolatki nie lubią wierszy (‘Teens Do Not Like Poems’), which was supposed to be published in 1968. But at that time, the author fell into disfavour with the authorities and his books, both for children and adults, were banned indiscriminately. Simply put, he was blacklisted. Consequently, the entire print run of Nastolatki nie lubią wierszy was to be destroyed. Which would have been a great loss, because Woroszylski’s anthology was great. I went to the printing house, I talked to the shift manager who happened to be a friend of mine. We decided that the first page should be reprinted, and the date of publication changed from 1968 to 1967. I made a big seven, which can still be seen today, because it does not match the rest of the digits – it is huge. And we also needed to bind the book. Luckily, in the bookbinding workshop we found a binding for a book of the same format, just a little bit thicker. We decided to use it. Today you can still see that the book’s “clothes” are too big. Obviously its distribution was later limited, but it did come out. A few years later, there were problems with Jan Brzechwa’s Pali się! (‘Fire!’), although there were no ideological objections to the author himself. The book was to be released in 1975, at a time when several huge fires of unknown origin broke out in Warsaw within a few days, ravaging the Central Department Store (later called “SMYK”) and destroying the Lazienkowski Bridge. The book remained in warehouse for about two years because of its large format and the cover lettering that was too conspicuous.

For many years you collaborated with Polish Television (TVP), creating stage designs for its programmes, not only those for children...

I had a good basis. I started my education at the State School of Visual Arts at Myśliwiecka Street, which was the second best art school after the Academy of Fine Arts (ASP). However, it was completely different from the Academy; it had such departments as graphics, book, poster, interior design, or scenography – a little bit of everything. My cooperation with television started with programmes about Scatterbrain, which were innovative at that time – the idea was to breathe new life into this character. Later I did various entertainment shows and even an opera with Gustaw Holoubek playing one of the leading parts.

So Gustaw Holoubek sang?

He did, in a way. It was Master Peter's Puppet Show by Manuel de Falla, an opera in one act based on an episode from Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, directed by Jan Kulma. It was 1958, the year Gustaw Holoubek made his debut on television. We had a performer for the role of Sancho Panza, but we were looking for someone tall and thin to play Don Quixote. We singled out two candidates, but they were both busy. A woman working at the artist engagement section remembered a young man who had just arrived from Krakow. We only asked her if he was skinny and tall. She nodded without blinking. That is how Holoubek was cast in the role of Don Quixote. The show went live, like everything else on television in those times.

What was the biggest surprise in your time at television?

My work for the Kabaret Starszych Panów (Old Gentlemen Cabaret). Cooperation with Przybora and Wasowski was a great thing. They would jump at all suggestions, they positively expected them. They liked gags such as taking out a 2-metre halberd from a 40-centimetre deep secretaire. It was a kind of creative game and a wonderful experience because from the very first reading, the programme grew; the actors, the director and the stage designer would put in their two pence worth, and the actors would eagerly accept it. And this was not obvious, since these ideas required the performers to be constantly ready for changes, for cooperation. Everything was evolving until the last moment. And then we would have three rehearsals with cameras, and that was it – the show went live.

When did you get tired of working for television?

It was not so much that I quit television; it was rather they who ended the relationship. I worked for them until martial law was announced. I did not want to make the children's programme Tik-Tak.

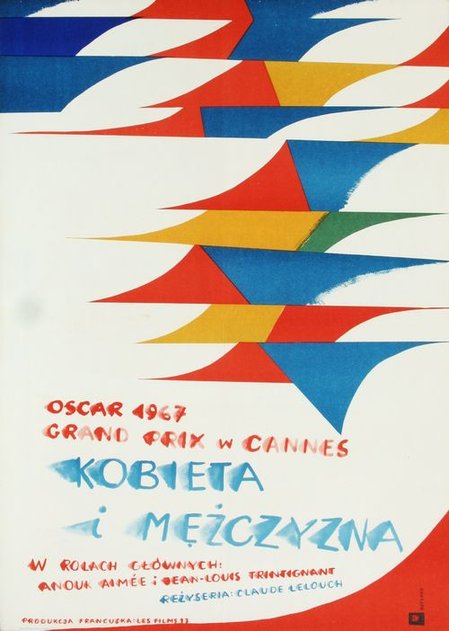

Posters are a separate field of your activity. They are very diverse – not just for children's movies, but also for adult ones, such as Lelouch's famous A Man & a Woman. There were also advertising posters. Is it true that in one of them, you encouraged people to eat codfish?

Have you seen such a poster? You are not likely to find it, because I never made it. But I made other posters for foodstuffs. For example, cheese. This year I had my first ever exhibition of posters in Lublin. Initially, there were supposed to be 30 at most, but it turned out that there are over 70 of them – from various fields, mostly movie, advertising and research posters. But I also designed a poster for Halka, the opera staged at the opening of the Grand Theatre in 1965.

Did you enjoy doing it?

Did you enjoy doing it?

If I hadn’t enjoyed doing it, I wouldn’t have accepted the work.

Does it mean that you only do what you like?

Once a journalist who was interviewing me said, “Now you can do anything you like.” I replied, “You are wrong. I cannot do anything I like but I cannot do what I don’t like either.” That's a big difference.

Have you never been forced to compromise during the 87 years of your life?

For sure there have been some compromises, but it also depends on what we call a compromise – because if it’s about changing the format or font, then yes, it used to happen.

But have there been any compromises regarding the authors you work with?

No. Edmund Niziurski, Jan Brzechwa, Adam Bahdaj were all great authors. For example, I often had trouble with Niziurski, because he would present me with three excellent ideas and I was faced with the difficult choice of which one to take, and which one to reject. And there was also Wanda Chotomska, with whom I work together on her debut book Tere-fere. She wrote texts that were great not only to read, but also to illustrate. Our cooperation was nicely concluded with her last book, Bobry mówią dzień dobry! (‘Beavers Say: Good Morning!’), for which I designed the artwork. Our collaboration was very successful.

But you also illustrated adult literature, for example a collection of poems about female names that you yourself wrote, titled Do wieńca wspomnień. The book is (for) adults-only.

Do you know of many recent fiction books for adults that contain illustrations? It used to be a normal thing before. Novels by Ignacy Kraszewski, Stefan Żeromski and Henryk Sienkiewicz were also published in illustrated versions. Jan Marcin Szancer also illustrated The Trilogy and Sir Thaddeus. Nobody considered it strange. Today it is a curiosity. Sometimes illustrations accompany poetry, but it is usually an ornament.

The evocative style of the characters you draw imposes itself very much on readers’ imagination. Too much so perhaps?

There are some funny stories about that. Konrad Nałęcki, who directed such youth movies as I ty zostaniesz Indianinem (‘You Too Can Become an Indian’) and Mniejszy szuka Dużego (‘Smaller Seeks the Big’) based on Wiktor Woroszylski's books, tried to cast actors according to my drawings. It was also the case with the series Unbelievable Adventures of Marek Piegus based on Edmund Niziurski's novel, directed by Mieczysław Waśkowski. Such were the readers’ expectations. But please remember that it is authors who created those suggestive characters – I only drew them.

Are books still important for young readers?

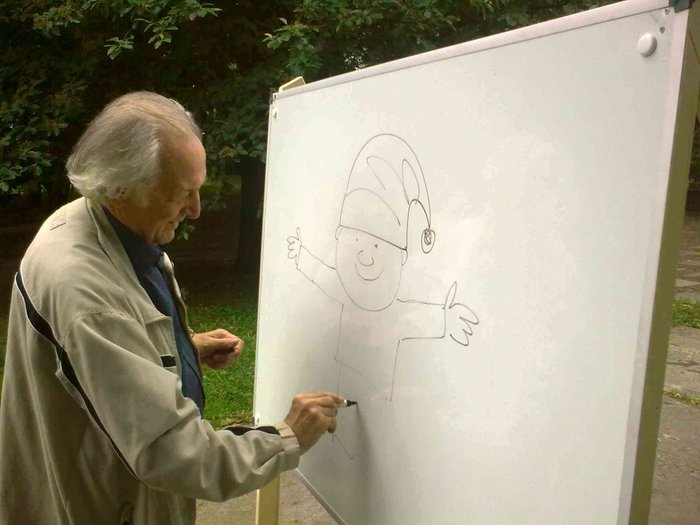

I hope that for some they are. Children's needs do not change. The fact that today they have mobile phones doesn’t prove anything. Small children are wonderful and they are the same everywhere. They are deprived of their natural sensitivity by their environment; their psychological independence, their way of thinking, associations and fantasy are taken away from them. Until they are deprived of it by the school, they are wonderful. Then it gets worse and worse. The younger the children, the more eager I am to meet with them. During one meeting you cannot teach anybody how to draw, but you can encourage, open and stimulate their imagination, so they follow their path. If out of the thirty children I meet, two or three will open up to their own imagination, that is a lot.

Source: “Rzeczpospolita”

07.09.2017