Conrad of our times

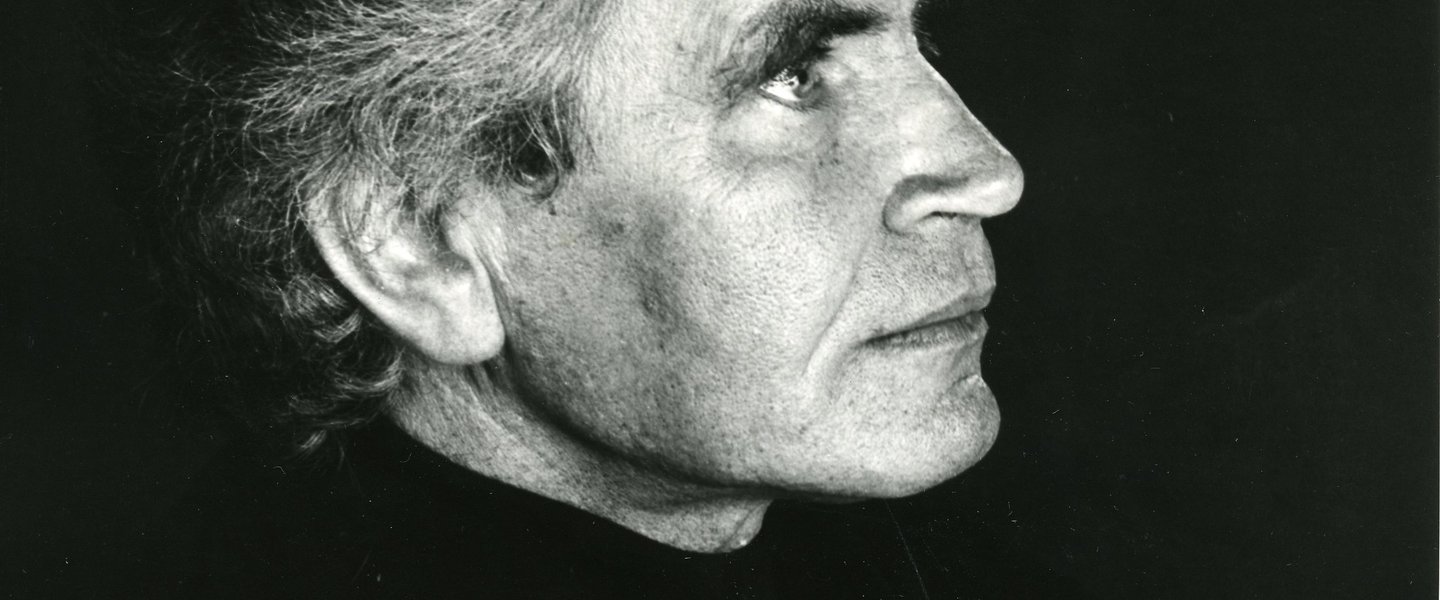

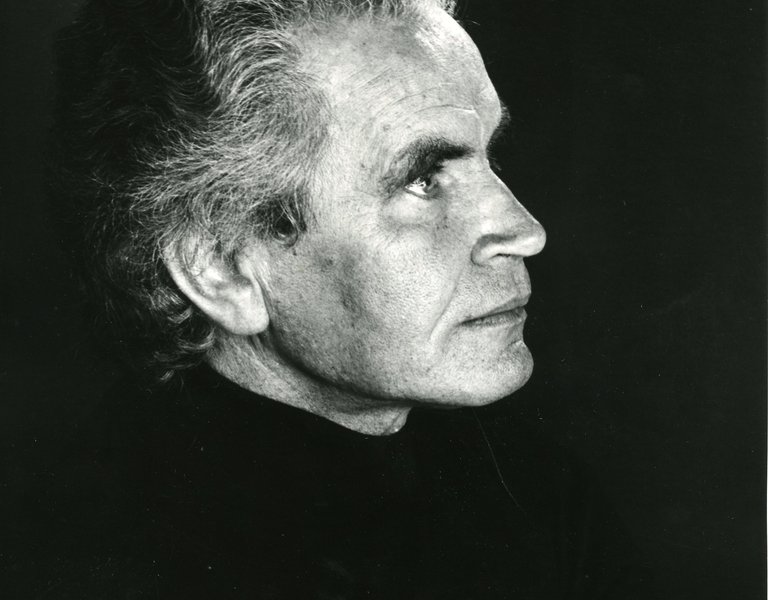

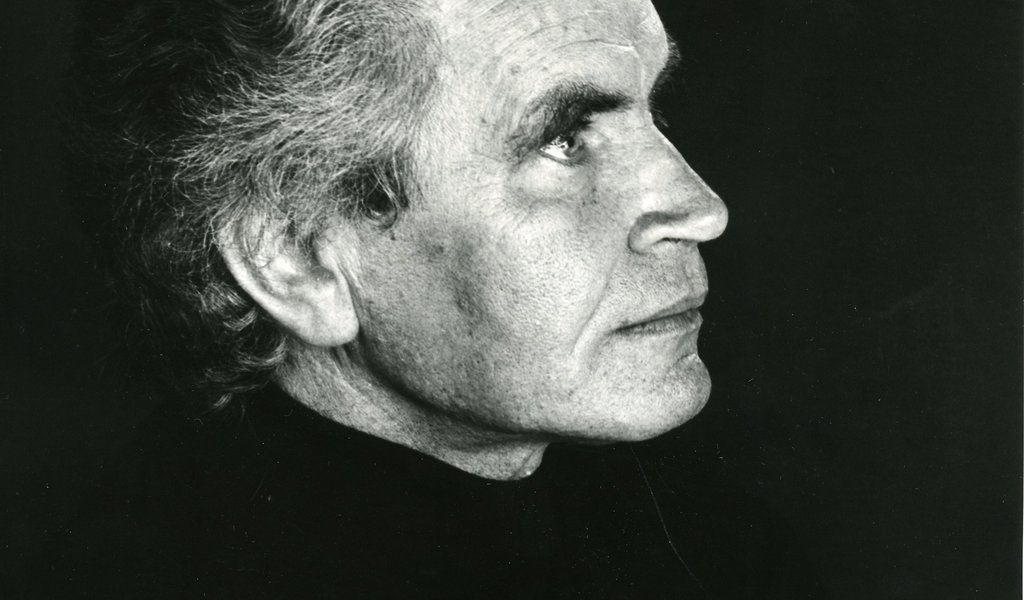

Representatives of the UK-based Jerzy Peterkiewicz Educational Foundation tell Poland.pl why the patron of their association is still important ten years after his death. Rosemary Hunt-Marciniak, Carol O'Brien and Alicja Moskal - literary translators and critics - knew the writer personally and despite the passage of years are still impressed by his work and his personality.

POLAND.PL: This year marks the 10th anniversary of the death of the writer and poet Jerzy Peterkiewicz. Last year we celebrated his 100th birthday, and yet despite a number of public events, it is hard to resist the feeling that he is still somewhat forgotten. Why should we remember him?

POLAND.PL: This year marks the 10th anniversary of the death of the writer and poet Jerzy Peterkiewicz. Last year we celebrated his 100th birthday, and yet despite a number of public events, it is hard to resist the feeling that he is still somewhat forgotten. Why should we remember him?

ROSEMARY HUNT-MARCINIAK, CAROL O'BRIEN, ALICJA MOSKAL: Jerzy Peterkiewicz was an original, creative force: a Polish poet, an English novelist, a sensitive translator, an acute critic, a brilliant teacher, a true European. He was a good writer in both Polish and English, and he was both a good poet and a good prose writer. He was also an accomplished draftsman.

His use of the English language – learnt only in his 20s – enabled him to give full voice to his imagination, and to vary his style, in his novels. His extensive reading of many literatures informed his literary criticism. He was precisely attuned to the rhythms and sounds of his native regional speech, and of standard Polish. His ear was finely tuned to the English language.

Descended from a rural community, before the German-Soviet aggression he managed to immerse himself in Warsaw city life, and eventually he found himself in exile in Britain. Which of these places was Peterkiewicz closest to, and which place did he consider to be ‘his’?

Of all the regions that Jerzy loved, his home region of Ziemia Dobrzynska was his deepest love, to which he returned in his thoughts as he grew old. He wrote about the region, visited it often, and his ashes were buried there at his request. In his middle years his involvement was with literary London, and in his early old age his passion for Andalusia almost obliterated other allegiances. He built a house in Spain, and found peace and consolation where the rhythms of life in the Spanish country side echoed those of Fabianki. But his deep devotion to Ziemia Dobrzynska was at the core of his being.

How did Peterkiewicz appear in the West?

He found his way to the West, as did many Polish exiles, by many and varied routes. He apparently was a correspondent for “Polska Zbrojna” when Polish intellectuals left Warsaw for Romania, and it was there that he wrote his first – and only Polish-language – novel Po chłopsku (‘A Peasant Way of Life’). He then found his way to London by various means.

Jerzy Peterkiewicz was the author of the beautiful Prayer to the Virgin of Skepe, a friend of Father Jan Twardowski, he translated poems by Karol Wojtyla (St. John Paul II) - can we call him a religious writer?

Peterkiewicz was a deeply religious man and he was a deeply serious poet. He wrote some religious poems, and translated others into English, but I would not call him a religious poet in the sense that John of the Cross, George Herbert or Gerard Manley Hopkins were clearly religious poets. He did not write religious poetry as did Jan Twardowski, or Bonifacy Miazek, and his devotion to Skepe is rather to a holy place. Jerzy Peterkiewicz’s seriousness about his own faith, however, infected all his work, including the poems he wrote, and certainly his translations of the poems of Pope John Paul II. But I still would not call him a religious poet.

The question of whether Europe is condemned to extinction is a civilization problem. Speaking of the possible fall of Europe, we are not thinking about its political subjugation to Asia or America, but rather about the full extraction of its culture, the diminishing attractiveness of multi-coloured regionalisms and cohesive universalism.

Politically, Europe is tired and is now verifying its ambitions with regard to the bleak post-war reality; but Europe is not willing to give up its longstanding leadership role: this is especially evident today in the strenuous publishing activity in all countries affected by several years of occupation, even in those places where communist control prevented bolder statements [...]

In our civilization there is always a deep sense of the insensitivity of the world. Vanitas vanitatum. In our civilization there is always the love of death, but love as a longing for God. Yes: God's love through death! Do not confuse the love of death with the fear of death. One should not confuse the sadness of people, the awareness of the mystery of original sin, with the hopelessness of the materialist pessimists; one should not confuse the Catholic approval of existence with the animalistic vitality of existentialism.

The man of Western civilization changes, he often seems to live on the brink of the abyss: but at the same time the western man believes in the brains and the heart, the wonders of miracles, and in the habit of work; a person of Catholic culture believes in the truth of redemption and in the sanctifying grace. [...] the essence and strength of our civilization is the ability to regenerate, the ability to cope with crises and the ability to avoid catastrophes - even it is only by a hair’s breadth. In the fight against Satan we are winning - also a hair’s breadth from catastrophe. Moral victories are not easy or boastful victories. There is no fanfare on the battlefield of sin.

But the waves of the Deluge fall in time - and in time the bird with an olive branch flies by, proclaiming deliverance from destruction. A true Christian and a true European is the same thing. They both remember the trusting colours of a flaming rainbow.

Jerzy Peterkiewicz, Prawo do życia czy prawo do upadku? (‘The Right to Life or the Right to Fall?’), 1946

[in: Europejskie wizje polskich pisarzy w XX wieku (‘The European Visions of Polish 20th Century Writers’), ed. M. Urbanowski, European Unity Library, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2011]

The anthology published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs titled Europejskie wizje polskich pisarzy w XX wieku (‘European Visions of Polish Writers in the Twentieth Century’, 2011) included the poem Pogrzeb Europy (‘Burial of Europe’, 1945) and the essay entitled Prawo do życia czy prawo do upadku? (‘The Right to Life or the Right to Fall?’, 1946). How did Peterkiewicz perceive the condition of the Old Continent? What kind of role did he see for Poland?

He believed deeply in the unity of European culture, and felt himself to belong in Europe rather than belonging in any individual country – Poland, England or Spain. He was at home in them all and felt they belonged with each other. As far as the politics of the European Union is concerned, it is not sure what he thought of the current state of play. But he certainly felt Poland to be a part of Europe.

The 10th anniversary of Jerzy Peterkiewicz's death is connected with global celebrations of the Year of Conrad. Peterkiewicz is often called the "Conrad of our times" - did both writers only share a common experience of a Poles' fate in exile or maybe something else?

The 10th anniversary of Jerzy Peterkiewicz's death is connected with global celebrations of the Year of Conrad. Peterkiewicz is often called the "Conrad of our times" - did both writers only share a common experience of a Poles' fate in exile or maybe something else?

The most obvious similarity between Peterkiewicz and Conrad lies in their ability to write in exciting colloquial, imaginative English despite the language not having been his mother tongue. Conrad was a master story-teller with the gift of bringing to life, and drawing his readers into, strange, remote places and describing the often troubled people who inhabited them. Conrad did not speak English fluently, and must have relied on others to polish his texts for publication. Peterkiewicz spoke good English; he experimented with style, place and characters in his novels, but he also wrote critical works and much else in English, and in Polish, and was a poet.

Most of his post-war books, including memoires, first appeared in the English language, and only then - often much later – in Polish. How important was Jerzy Peterkiewicz for British literature?

The significance of Peterkiewicz’s writing for British literature lies in his ability, already mentioned, to write superb English prose: varied in style, colourful in expression and profound in content. While his anthology of English poetry in Polish revealed some of the wonders of English literature to Polish readers, so his translations of Polish poetry and prose of all periods, in particular of the works of Cyprian Norwid, and of Karol Wojtyla, opened a window on the richness of Polish literature.

Jerzy Peterkiewicz was also a skilled translator. He translated classics of Polish literature headed by Cyprian Kamil Norwid into English, while anthologies of English literature appeared in Polish. Was he primarily a poet of "authenticity", a subtle essayist, a serious writer, or perhaps a translator?

I think that he would have liked to be remembered above all as a Polish poet, and as a translator, bridging the gaps between two great literary cultures. He is also known as a subtle essayist and, moreover, as a communicator of ideas. His career began among writers drawing on their peasant backgrounds and he never rejected that element of his life, but in the many facets of his work he became a true man of letters.

Poland.pl

JERZY PETERKIEWICZ EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION

It was Jerzy Peterkiewicz’s dearest wish to leave a legacy for the benefit of those who. Like himself in his own early years, cannot afford to write or study as they wish.

The Foundation was therefore set up in his name in accordance with the conditions set down in his Will to “provide bursaries to further a knowledge, appreciation and understanding of Polish literature and other writing of artistic, historic, aesthetic and cultural value among young students and writers of Polish descent”.

06.10.2017