Europe, Europe...

"You tell us: Europe. And whenever our milk goes sour, humpbacked dwarves crawl out and pee in the pots," Sławomir Mrożek wrote years ago in his characteristic humorous style. This does not mean that we quickly resigned from our European aspirations.

One thing somehow led to another, and a year after the fateful October 1956, the Warsaw Salon decided we must have the kind of “Europe” we deserve. “It looked promising,” writer Marek Hłasko recalled. “Jerzy Andrzejewski was the editor-in-chief, and Jerzy was in excellent form back then. We prepared the first issue and it probably was quite good, but at the Central Committee we were told that the Party saw no need to print a publication of this type at the present stage.”

One thing somehow led to another, and a year after the fateful October 1956, the Warsaw Salon decided we must have the kind of “Europe” we deserve. “It looked promising,” writer Marek Hłasko recalled. “Jerzy Andrzejewski was the editor-in-chief, and Jerzy was in excellent form back then. We prepared the first issue and it probably was quite good, but at the Central Committee we were told that the Party saw no need to print a publication of this type at the present stage.”

Several years ago, that still-born “Europa”, of which only a single trial issue ever appeared, was honoured. But a reprint attracted little attention. Now, a much earlier and far more interesting “Europa” is being remembered. A monthly by that name was issued in 1929-1930, edited by Stanisław Baczyński, known to the average member of the Polish intelligentsia merely as the father of poet Krzysztof Baczyński. Those slightly more clued in sometimes add that Krzysztof's parents were separated and the father was a literary critic with verging on communism.

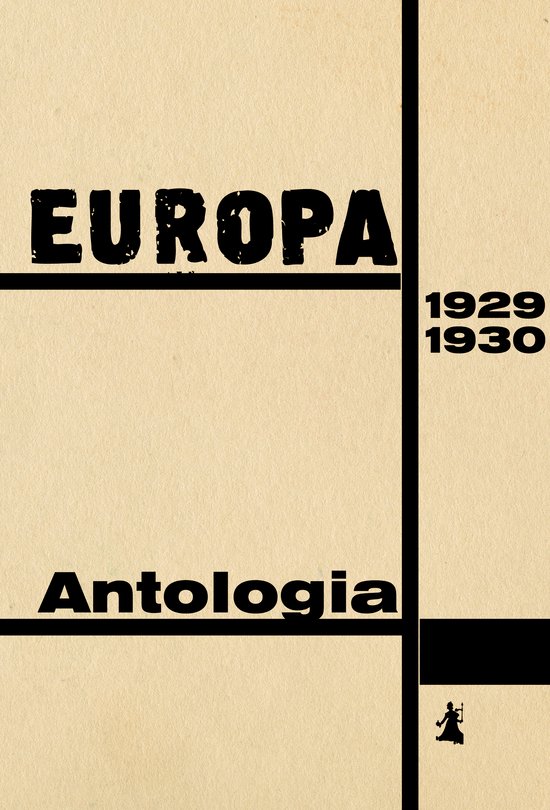

An anthology of “Europa” texts recently published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs illustrates what these views essentially consisted of. Its superb graphic format alludes to the 80 year-old publication. No, that's no error – the Ministry does publish books forming part of a series titled The European Unity Library.

“By subscribing to ‘Europa’ you support free and independent Polish thinking and contribute to the victory and development of the new Poland in Europe, trampled by hypocrisy and moral misery” – was the way the journal sought to attract readers. Texts from “Europe” were selected and edited by Professor Andrzej S. Kowalczyk. Baczyński's articles were the most important part of the journal which collapsed not for political but financial reasons. Another problem was that it simply could not find a place for itself on the publishing market, which was dominated by “Wiadomości Literackie” and “Prosto z Mostu”.

“As long as the editor-in-chief influenced things and was able to,” Kowalczyk wrote, “he emphasised respect for European standards, modernisation of the Polish consciousness and the creation of a new, democratic civic ethos.” As for Baczyński's alleged pro-communist leanings, I recommend his review of Bruno Jasieński's then en vogue book I Burn Paris. Baczyński tore it to shreds when he wrote: “God forbid stalks of grain ever sway in the wind on Place de la Concorde in Paris. That vision of Jasieński's simply proves that he understands neither the substance nor sense of modern civilisation, nor the goal of the ideology he apparently espouses.” The author of these words regarded himself as a socialist, although he did not treat that and other '-isms' with any great gravitas and he rejected communism outright.

Baczyński's friend Edmund Semil characterised him thus: “He spouted the unvarnished truth and was concerned about retaining his independence. But he was no outsider. His vitriolic remarks, uttered in the name of social justice, realism in literature and the writer's conscience, could humiliate many a soul. He did not enter into liaisons or clinch back-room deals with any one. He disregarded personal advantage, scorned all things sleazy and ridiculed both braggadocio and heroism. As a result, he was not well-liked by many”.

This was the “Europa” that he edited, in which Jalu Kurek presented or – in his own words – exposed a new position on poetry. It turned out that their group intended to: “Combat the clownish tragedy of a Tuwim, dabbling with erotic passion in words which he could neither command, nor defeat and to which he succumbed like a child; the indolence of a Lechoń, overcome by hope and enthusiasm, who amid all the flattery came to believe he was a star and ended up as a slacker; the snobbery of a Słonimski, afflicted by stale jokes and geriatric contentiousness diluting his absolutely last drop of lyricism; the boring phraseology of a Zegadłowicz bordering on graphomania, the incurable mania for writing; the female laments of an Iłłakiewiczówna who between litanies and rhymed name-related fortune-telling could not find a valid reason for writing; the parasitic Skamander literary group, the summer-holiday ideology of the “Czartak” group and the unclear inferior three-quarters of “Kwadryga”.

Avant-gardism, which for Kurek was the remedy for all the ills of Polish literature, was no key, or rather, skeleton key for “Europa”'s leading author, Karol Irzykowski (giving way to Stanisław Baczyński's, of course). In “Europa”’s programme text titled Godność (A Dignity), he wrote: “Literature is becoming a racetrack where everyone bets on their favourite. To facilitate the game, like poker chips, silly divisions and ranks have been thought up: talents, semi-talents, geniuses, etc. There is lip-smacking to signal delight or the well-known smirk of condemnation anticipating one's listeners solidarity. In the realm of arbitrary criticism, the Skamandrites are in the lead. Without any evidence, claiming their word of honour should suffice, they hand down conclusive verdicts. Verdicts are their obsession.”

Has anything changed since then? Yes indeed – the Skamandrites have all died out.

Author: Krzysztof Masłoń

Source: “Do Rzeczy”

The European Unity Library (Biblioteka Jedności Europejskiej), under the patronage of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, is being published in interesting times. The consolidation of Polish membership of the European Union, changes in the euro area, the expansion of the Union, demographic processes, seismic shifts on the geopolitical map and dozens of other factors make for a fascinating world and continent.

The books to appear in this series will be devoted to the identity of Europe, its borders, its civilizational heritage, and its future. Outstanding authors from various academic and cultural backgrounds have been invited to work with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the impressive results of their work are now reaching readers.

12.06.2017