Only the truth is interesting

The centenary of regaining independence by Poland is also an opportunity to pay tribute to the 100th anniversary of independent Polish culture. One its most eminent representatives was no doubt Józef Mackiewicz – a Polish writer, reporter and political journalist. January 31 marks the 32nd anniversary of his death. On this occasion Poland.pl talks to Prof. Maciej Urbanowski, chairman of the Józef Mackiewicz Literary Prize.

POLAND.PL: Despite the passage of time, books by Józef Mackiewicz remain extremely popular. Further editions of his books and biographical entries are available. How would you explain this phenomenon? Why did Poles read - in exile and in the anti-communist underground publishing – and continue to still read the books of the 'fowler of Vilnius'?

POLAND.PL: Despite the passage of time, books by Józef Mackiewicz remain extremely popular. Further editions of his books and biographical entries are available. How would you explain this phenomenon? Why did Poles read - in exile and in the anti-communist underground publishing – and continue to still read the books of the 'fowler of Vilnius'?

PROF. MACIEJ URBANOWSKI: Simply put, we read books by Józef Mackiewicz, because he is a very prominent prose writer, an author of excellent, timeless novels and short stories, as well as journalism that is still thought provoking. Add to this his dramatic biography and we will better understand the reasons for the fascination with Mackiewicz, who still appears as an anathema writer and a great outsider of modern Polish literature. And still unknown, his works continue to be discovered. In recent years, the book Prawda w oczy nie kole (‘The Truth Does Not Hurt’) was discovered and published after many years although it was written during the war. We are also becoming acquainted with very interesting letters penned by the writer.

President Lech Kaczyński wrote that Józef Mackiewicz’s books taught ‘bitter wisdom: they helped understand the essence of the red enslavement, the ways in which the Soviet system perceived reality and broke the will of individual people and entire social groups’. Does Mackiewicz's ‘bitter wisdom’ still matter today? Can one talk of its universal reach?

President Lech Kaczyński wrote that Józef Mackiewicz’s books taught ‘bitter wisdom: they helped understand the essence of the red enslavement, the ways in which the Soviet system perceived reality and broke the will of individual people and entire social groups’. Does Mackiewicz's ‘bitter wisdom’ still matter today? Can one talk of its universal reach?

Communism was indeed the central biographical experience of Mackiewicz and, in fact, the central theme of his prose. What is communism, why it wins, what are the effects of this victory, how to overcome Communism - these are the issues that Mackiewicz perfectly studied with literary tools. And thus showing how communism captivates minds using the example of the fate of specific heroes, operating in a realistically, vividly created geographical, social, and historical space. It is worth recalling that Mackiewicz was an ornithologist by education, which may explain not only his beautiful descriptions of nature, but also the specific naturalism with which he looked at history and mankind. Therefore, he may not have succumbed to ideological illusions, he refuted various taboos, for example nationalistic or progressive ones. This was his 'bitter wisdom'. It did not get outdated, because in fact Mackiewicz still wrote about the freedom of the individual, defending this freedom, but also showing how we can be deprived of this freedom. For example, by means of lying, manipulating the truth, or referring to the interests of collective, inhuman ideologies. Or, finally, Mackiewicz's political realism, which Mackiewicz did not particularly like, even though he was not a believer in any form of romanticism. The writer also paid a high price for clinging on to these ‘bitter wisdoms’, staying true to his motto 'only the truth is interesting.' That price was emigration, loneliness, poverty...

Mackiewicz's fate is a peculiar symbol of the fate of Poles in the 20th century. He was a volunteer in the Polish-Bolshevik war in 1920, an important participant in the literary and political disputes of the Second Polish Republic, a member of the resistance during the 1939-1945 occupation and, finally, an émigré on the "West European pavement". All these stages of life can be felt in his writing.

Mackiewicz's fate is a peculiar symbol of the fate of Poles in the 20th century. He was a volunteer in the Polish-Bolshevik war in 1920, an important participant in the literary and political disputes of the Second Polish Republic, a member of the resistance during the 1939-1945 occupation and, finally, an émigré on the "West European pavement". All these stages of life can be felt in his writing.

Mackiewicz was born in 1902 in St. Petersburg, he died in 1985 in Munich, so he was a witness to actually the most important events of the 20th century. He did not live to see the tearing down of the Berlin Wall, which he probably would have been sceptical about. His writing contains autobiographical elements, although it is a hidden biography. On the one hand, Mackiewicz continues the pattern of great realism straight from the nineteenth century, on the other hand, he takes up topics that have affected his life. This is how it is in two of his great novels: The Free Left on the Polish-Bolshevik War, and the Road to Nowhere, about the Soviet occupation of the Vilnius region in 1939-1941. The heroes of these books resemble the author himself, who, however, suppresses the memoir character of these novels by introducing a number of other, interestingly built figures, but also, for example, authentic characters or recalling historical documents.

Mackiewicz is also called the 'witness of the twentieth century', someone who documented the crimes of 20th-century totalitarianism. He described, among others, the crime committed by Lithuanians on Poles and Jews in Ponary, he also took part in the exhumation of the corpses of Polish officers in Katyn, murdered by the Soviets. He later published reports from the war, including Ponary-Baza and Fumes over Katyn, about which Polish Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz wrote that 'as long as there is Polish literature, these two twentieth-century horrific records should be constantly returned to'.

Mackiewicz is also called the 'witness of the twentieth century', someone who documented the crimes of 20th-century totalitarianism. He described, among others, the crime committed by Lithuanians on Poles and Jews in Ponary, he also took part in the exhumation of the corpses of Polish officers in Katyn, murdered by the Soviets. He later published reports from the war, including Ponary-Baza and Fumes over Katyn, about which Polish Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz wrote that 'as long as there is Polish literature, these two twentieth-century horrific records should be constantly returned to'.

Yes, these are extremely important and unique testimonies in world literature, shocking and excellently written. It is worth recalling that Mackiewicz was a talented reporter and that his first important book was Bunt rojstów (‘The Rebellion of Roysts’) published in 1938, a description of a trip to the north-eastern borderlands of interwar Poland. A bitter description, critical, far from the official optimistic line, full of great descriptions and wise comments.  This is also the case with these testimonies depicting the communist and Nazi totalitarian crimes. In addition, Mackiewicz's political incongruity was such that, unlike many 20th-century European writers, he did not justify the crime of one form of totalitarian with the crimes of another, but was an enemy of both. On the other hand, he said that communism is more dangerous than Nazism in the sense that the second kills ‘only’ physically, while the other also kills spiritually, morally.

This is also the case with these testimonies depicting the communist and Nazi totalitarian crimes. In addition, Mackiewicz's political incongruity was such that, unlike many 20th-century European writers, he did not justify the crime of one form of totalitarian with the crimes of another, but was an enemy of both. On the other hand, he said that communism is more dangerous than Nazism in the sense that the second kills ‘only’ physically, while the other also kills spiritually, morally.

How is Józef Mackiewicz received abroad? The voice of the multicultural Eastern Borderlands (Kresy), a resident of Vilnius, Warsaw, London and Munich? Does Mackiewicz remain only a Polish writer, a local writer, or is he an important author of world literature?

I am afraid that the attention given to him abroad does not live up to the prominence of his writing. Some of his books have been translated into many languages, for example The Road to Nowhere is available in French, English, German, Hungarian, Lithuanian. Hungarians like to translate Józef Mackiewicz the most. It is hard to claim, however, that Mackiewicz is a writer widely known outside of Poland and for that matter a global writer. However, he covered issues that are far from local, he is a writer describing the key historical and existential experiences of a large part of Europeans in the 20th century.

It seems that anti-Communism in Europe is not only an underestimated phenomenon; it is simply not noticed by its critics. The fact that communism is spreading in Europe, as in France and Italy, right in front of the eyes of the observer, is challenging the ground on which this is happening. We say that pro-Communist moods are pitted into the ground... What? Of course, not communist ones. It is known, however, that every organism that develops under natural conditions (i.e. in a given case in a free system) generates the self-defence of tissues against diseases. In this way, the non-communist basis is transformed by a natural reaction to - anti-communism. There are many Communists, but there are undoubtedly more anti-Communists. One could risk the claim that Europe is now inhabited mainly by anti-Communists. They are therefore the greatest force in it. [...]

If Bolshevism threatened only one country in Europe, one could rely on the national patriotism of this one state. The error in today's calculation, however, is that Bolshevism threatens all Europeans. And that is why it is possible to oppose it only to the equivalent factor - human patriotism. After disputing a bit, let's give way to - European patriotism.

Józef Mackiewicz, A Trip to Europe, [in: Europejskie wizje polskich pisarzy w XX wieku ('The European Visions of Polish 20th Century Writers'), ed. M. Urbanowski, European Unity Library, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2011]

Some time ago you included his essay in a collection titled Europejskie wizje polskich pisarzy w XX wieku ('The European Visions of Polish 20th Century Writers') published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. How did Mackiewicz view the Old Continent, how did he see Poland's place in Europe?

In his famous self-description, Mackiewicz spoke about himself as follows: ‘profession - writer, nationality - anti-Communist, beliefs - counter-revolutionary, country of origin - Eastern Europe’. This says something about his vision of Europe, which was firmly rooted in the idea of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and therefore of a community in which nations, especially the small ones coexist with each other, respecting their locality and autonomy, without imposing their own values, especially religious and national ones, and at the same time, if necessary, acting jointly against potential external threats. Mackiewicz wanted Poles to respect the separateness of the nations of Central and Eastern Europe and to be able to support them in the fight against a communist threat, if necessary. It was also important for Mackiewicz to emphasize that communism is not synonymous with Russia. He actually had a similar attitude with regard to Germany.

The Józef Mackiewicz Prize has been awarded since 2002. What significance does it have for the popularization of new Polish literature? Perhaps it is worth considering also distinguishing foreign writers - those who have ties with Poland and for whom, as for Mackiewicz, ‘only the truth is interesting’?

The Józef Mackiewicz Prize has been awarded since 2002. What significance does it have for the popularization of new Polish literature? Perhaps it is worth considering also distinguishing foreign writers - those who have ties with Poland and for whom, as for Mackiewicz, ‘only the truth is interesting’?

The latter is an interesting idea that one should probably think about. For now, we do indeed present the award to Polish writers, especially prose writers who refer to Mackiewicz in their work, whether it's taking up his subjects, or continuing a certain aesthetics, or even taking a specific, nonconformist attitude towards the present or the past. I think that we point to important phenomena in new Polish literature and that we were able to honour interesting books as well as interesting writers. Let me remind you that our laureates include different artists such as Wojciech Albiński, Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz, Eustachy Rylski, Wojciech Wencel, Bronisław Wildstein and Szczepan Twardoch. Today, they are the biggest names in Polish literature.

Poland.pl

JÓZEF MACKIEWICZ LITERARY PRIZE

A Polish literary prize awarded since 2002, created to commemorate Józef Mackiewicz and his work. It is awarded annually, and the announcement of results and the awards ceremony distinguishing the laureates takes place on November 11, the Independence Day of Poland. The award is bestowed by the chapter which deals with literary works (novels, essays, poetry) and journalistic (including political) and scientific literary and critical literary dissertations written in Polish by living authors, published in the previous year and submitted by publishers to the competition.

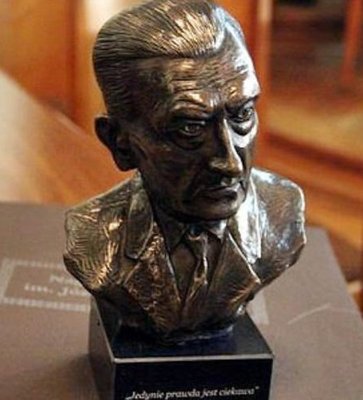

Nominations for the award are announced in the summer, usually constituting 10 books. From among these authors, the laureate of the prize is selected and receives 10,000 dollars and a gold medal with the portrait of the patron of the award and his literary credo: 'Jedynie prawda jest ciekawa' ('Only the truth is interesting').

30.01.2018