Poland on the Mediterranean Sea

At a time when Euro-enthusiasm becomes an alternative to patriotism, it is worth recalling what our writers had to say about Polish Europeanism.

An anthology of relevant texts, edited by Professor Maciej Urbanowski and published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, offers an opportunity to do this. Let me draw the reader’s attention to the publisher because this fact alone means that European Visions of Polish 20th-Century Writers complements pro-European and pro-Union activities.

This is indeed true, but fortunately Urbanowski’s work has nothing to do with propaganda, and a careful reading of the texts that he has included in it written by authors of diverse orientations convincingly proves that nothing is obvious here. What are we supposed to do with the fact that we are all thrilled with Jan Sebastian Bach’s music, which we regard as Europe’s common heritage, but, as Jan Polkowski wrote in his poem Europa (‘Europe’) in 1987 “[…]we are mortal and above all mortal,/ organs pray for us,/ while we stand on a dry plain in soldier greatcoats/ surrounded by lice and metal scrap.”

Internationalism and nomadism

Internationalism and nomadism

From a historical perspective, one would have to agree with Antoni Słonimski, who in 1930 prophesized that a future chronicler would write the following: “The first lecture in the Pan-European Union in the capital of Poland was received with hostility. The audience hurled insults at the lecturer." The lecturer was Count Coudenhove-Kalergi, author of the then renowned work Pan-Europa, who advocated, as Adolf Nowaczyński wrote about him – “eternal peace, brotherhood of nations, a new order of the world, an era of harmony among nations and states." The count’s genealogy was impressive. His great-grandmother Tekla Górska was Polish, his grandmother was the famous Maria Kalergis-Muchanow, née Nesselrode, not only Norwid’s muse but also that of Napoleon II and Bismarck, a confidante of Brahms and Wagner, a student and eminent interpreter of Chopin. Bearing in mind that the count was also a grandson of a Greek, a son of a Japanese, an Austrian aristocrat and a citizen of Czechoslovakia, it is little wonder that Nowaczyński, whose sympathies lay in the national camp, detected in his pan-European ideas traces of “romantic nomadism”, “spiritual internationalism” and even “national deracination.”

On 8 March 1930 Mr Coudenhove-Kalergi, President of the Paneuropean Union, gave a lecture at the University of Warsaw which was described by Antoni Słonimski in these words: “The hall was filled with a select audience and university students. (...)When cher compte et président finally reached the lectern, when the splendidly dressed ladies from diplomacy and aristocracy greeted him with applause, when the wife of the French Ambassador eyed the handsome lecturer through her binoculars, and the officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs smoothed their ties, someone started screaming bluntly and very loudly: «Jews go away!», «Germans go away!», «Masons go away!», «Go to Russia!». A horrendous tumult, din and chaos reigned. A bunch of students from the youth section of the National Democratic Movement were creating a commotion for twenty minutes. Those young people who believed that Count Coudenhove-Kalergi was a Jew, demanded that he go to Russia. They kept on repeating this weird demand without being stopped by anybody. His Magnificence Rector of the University did not feel it right to defend his guest. He left the hall.”

To Paris through Odessa

Thus public opinion was as divided as our writers were over the issue of the future the United States of Europe (this is how the future European Community was generally called). It should be remembered that the regaining of independence in 1918 did not spur pan-European feelings.

Karol Ludwik Koniński was strongly against the vision of a united Europe which was equated with the abolishment of nation states and supported the idea of a federation of nations. Józef Wittlin discussed quite favourably Pierre Drieu la Rochelle's pan-European ideas (which led him to collaborate with the Third Reich) in “Wiadomości Literackie” weekly.

Polish writers were never short of exotic ideas, as demonstrated by Andrzej Szczypiorski’s articles in the end of the 1970s. The writer recalled grandiosely the last days of war, when – as he wrote – “the soldiers of the East and West were raising cries of a happy victorious alliance on the Elbe river. Frenchmen from Sachsenhausen were heading to Paris through Warsaw, Kiev and Odessa, and Soviet POWs from Loire were trailing themselves (sic) to their motherland through the North Sea, Norway, Sweden, and Finland. That spring there were no borders, just a common, European string of people making their way to freedom.” According to Szczypiorski, those emotions could be a basis for building “a new model of European existence – based on freedom, peace and security.”

The author of the poem Niedziela, godzina 21.10 (‘Sunday, 9.10 pm.’, 1967) blamed the West German revanchists for the fact that this did not happen. He offered comfort to readers, though, by saying that “in the year of the 50th anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution, the communist movement extends its hand in friendship to all of Europe, thus continuing a programme of coexistence, enriched with new elements."

The gist of artistry

The gist of artistry

Fortunately, in the 20th century there were also Polish writers who were genuinely enraptured by the concept of a united Europe. Stanisław Brzozowski recalled as early as in 1910 that “Europe is not an empty word” and in Legenda Młodej PoIski (‘The Legend of Young Poland’) he stigmatised the civilizational backwardness of Poland in comparison to the West and the anachronism of Polish literature and culture. As we know well, later on Witold Gombrowicz expressed quite a different opinion in his Journals. Poland’s attempts to catch up with Europe did not appeal to him in the slightest. However, this would happen after the WWII trauma, which made Europe so unbearable to some of our writers that they declared its demise, just as Jerzy Pietrkiewicz did. As for Andrzej Bobkowski, he packed his belongings and moved to Guatemala, seeing in Europe only old age and passivity.

Bobkowski could not come to terms with the Western part of Europe forgetting the Eastern one. He wrote that “one of the features of a profound culture is discretion, the ability to refrain from raising sensitive topics. The European culture reached its apex in this area. Representatives of Eastern Europe have to squeeze into European congresses almost by force; the West European press actually makes you believe that Europe ends with the territories where you can still find pieces of chewing gum spat out by American defenders and guardians (...)? A comfortable and cowardly pars pro toto has replaced the concept of Europe, and its very sense and contents melted in it so completely that even the cleverest of Europeans do not realize it.”

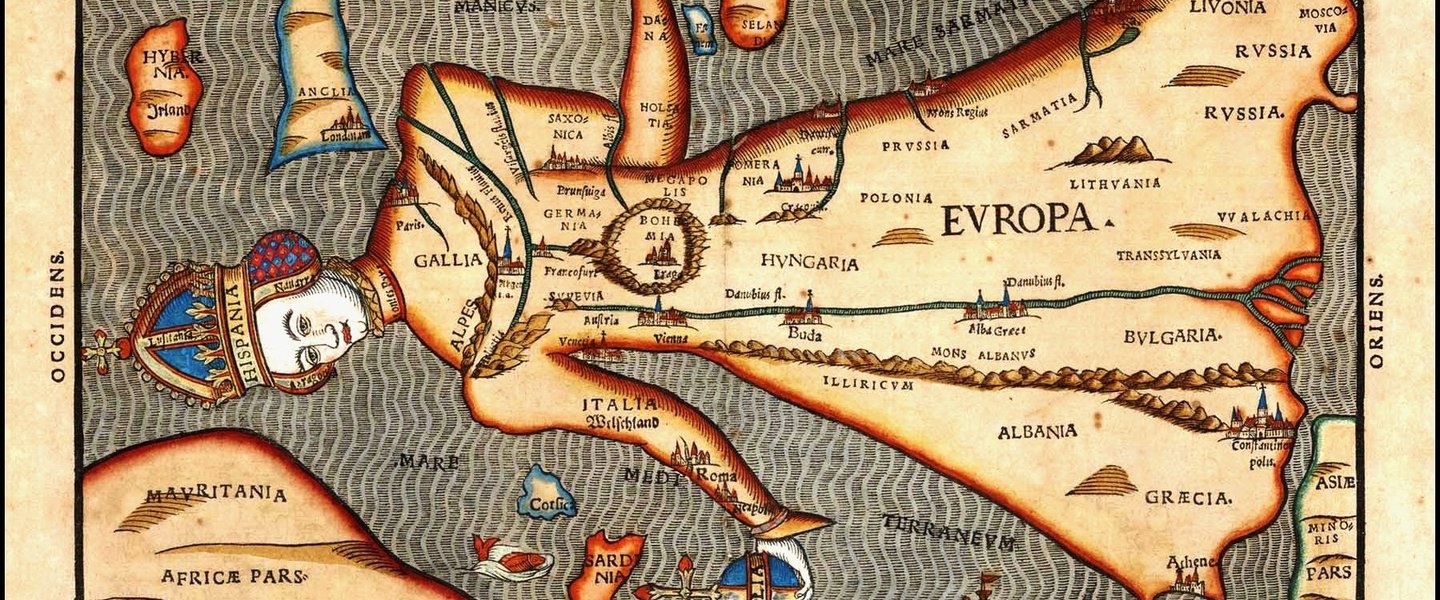

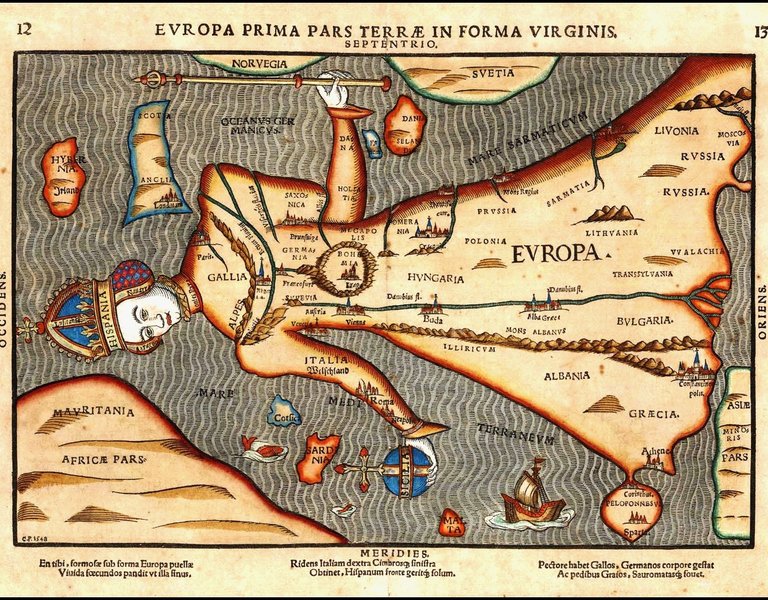

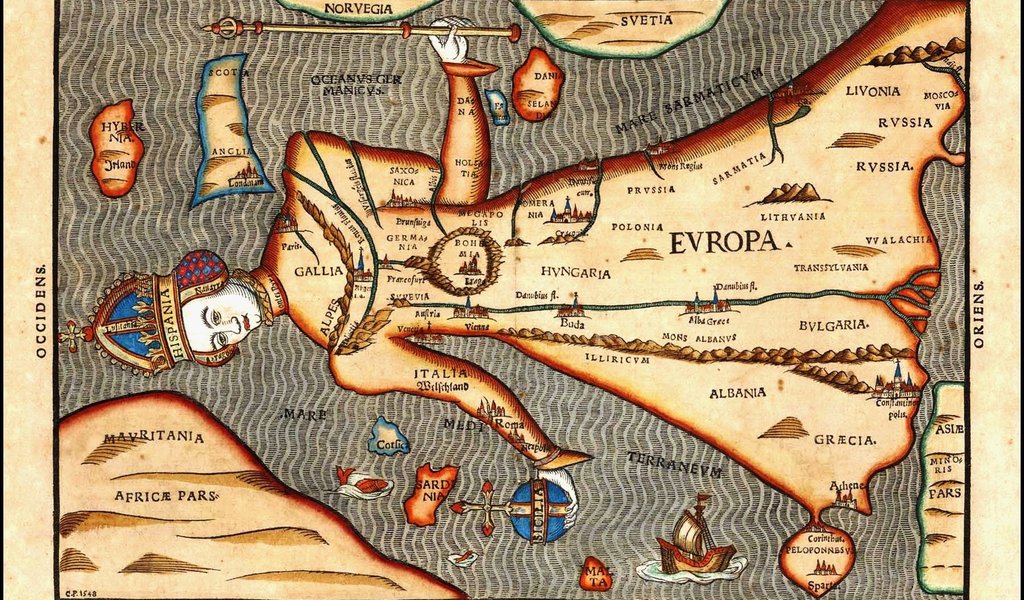

However, while some writers ran away from Europe, both symbolically and physically, others returned to it. This was especially the case with those who came to believe after Stalinist experiences that a pro-West orientation is the only sensible direction for Poland, which had been enslaved for no one knows how long and a salubrious gulp of fresh air for our culture was subjected to Bolshevisation. This is why Jan Parandowski would argue so persistently that in a spiritual sense Poland is situated by the Mediterranean, whereas Zygmunt Kubiak would seek and find Latins on the Vistula River. “Europeans” will emphasize the classicism of our culture and as far as possible, highlight the differences which distinguish us from the East, equated with Russia, the Soviets, or with Asia. It is worth recalling here a forgotten writer and critic who was killed in the Warsaw Rising, Włodzimierz Pietrzak. He managed to publish a text Miedzy Wschodem a Zachodem (‘Between West and East’) just before the outbreak of the war in which he claimed strongly: “Poland’s adherence to the Latin civilization should be an axiom.”

If one does not approve of Pietrzak’s connections with the Confederation of the Nation, then one should at least consider the words of John Paul II spoken in Santiago de Compostela back in 1982, when the Pope was dwelling over Europe and said in no unclear terms: “The history of shaping European nations develops in parallel to evangelisation, to an extent that Europe’s borders coincide with the permeating range of the Gospel. (...) Indeed, it is not possible to understand the European identity without Christianity. It is in Christianity that common roots are planted, from which the civilization of the Old Continent grew and matured, along with its culture, dynamism, and entrepreneurial spirit, (...) in one word, all that reflects its glory.”

It is absolutely natural that when we say “Europe” today, we ask straight away “What kind of Europe?” Czesław Miłosz, who defended Europe, wrote that it preserves the concept of sacredness and the tragic nature of existence, and while discovering history in its specific dimension, it differs both from America and Russia. Miłosz, who was pro-European also in his non-literary pronouncements, wrote an overwhelmingly bitter poem in 1953 Dziecię Europy (‘Child of Europe’), which remains utterly relevant, even though seemingly everything has changed. Europe has changed, we have changed, only this “child”, this “Inheritor of Gothic cathedrals, of baroque churches,” has not changed a bit.

Author: Krzysztof Masłoń

Source: “Rzeczpospolita”

The European Unity Library (Biblioteka Jedności Europejskiej), under the patronage of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, is being published in interesting times. The consolidation of Polish membership of the European Union, changes in the euro area, the expansion of the Union, demographic processes, seismic shifts on the geopolitical map and dozens of other factors make for a fascinating world and continent.

The books to appear in this series will be devoted to the identity of Europe, its borders, its civilizational heritage, and its future. Outstanding authors from various academic and cultural backgrounds have been invited to work with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the impressive results of their work are now reaching readers.

17.05.2017