Poles in Europe’s doorway

Europe’s most egoistic nation, reckless adventurers trying to mire the West in dangerous rows with Russia, a reserve of reactionary Catholicism – this is how Poland and Poles are portrayed in the salons of the Old Continent. This, in turn, encourages Poland’s Euro-enthusiastic elite to embarrass their compatriots with reports of the low esteem with which locals in Berlin, Brussels and Paris hold their country in.

One would think that the results of the Brexit referendum should have cooled the enthusiasm of Polish advocates of Europe’s federalisation, but nothing of the sort has occurred. Following in the footsteps of their EU institution masters, Poland’s Euro-enthusiasts have actually stepped up their campaign against the “demons of Polish nationalism”. Contrary to intellectual tradition, which should be its principal legacy, it is concepts such as these that provide Polish politics with leverage.

The EU’s founding fathers were not only Konrad Adenauer, Jean Monnet, Robert Schuman and Alcide de Gaspari. There were also perhaps lesser known Poles who had given serious thought to the concept of European integration even before the 1951 Paris Treaty created the European Community of Coal and Steel.

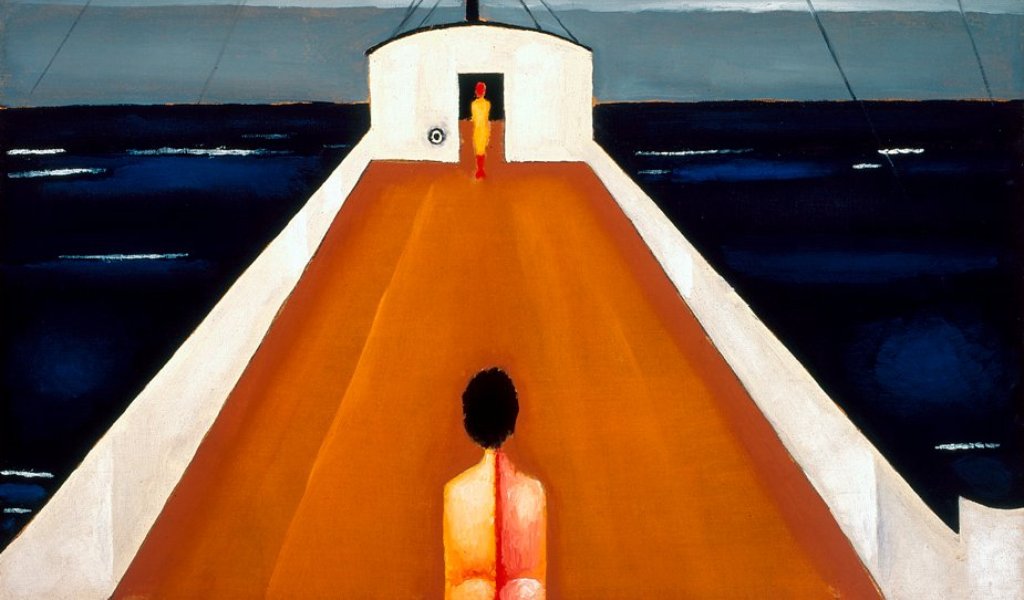

Their legacy is being promoted by Poland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which for nearly a decade has been publishing a series titled European Unity Library (Biblioteka Jedności Europejskiej), regardless of the political option in power. Particularly worthy of note are two anthologies: O jedność Europy (‘Towards a United Europe’) and Europejskie wizje polskich pisarzy w XX wieku (‘The European Visions of Polish 20th-Century Writers’).

Both books evoke a sentiment of déjà vu. The debates that took place during the 20-year interbellum, in the years of the Second World War and finally when the concept of European integration had assumed an institutional framework, remind one of today’s discussions held on the occasion of the recent British referendum.

A Polish squire’s concern

A Polish squire’s concern

Today the basic question regarding the European Union’s future is whether the organisation is to become a federal super-power or a confederation of sovereign states. Back in the interwar period such dilemmas did not exist, although various concepts of integration had begun to appear.

First of all, one should mention the Pan-European movement established in 1922. Its initiator was the Austrian aristocrat and diplomat Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi. The Pan-Europeans recognised the weakness of the League of Nations. On the one hand, they wanted to prevent a repeat of the nightmare of the Great War, on the other – to protect the continent from Soviet imperialism.

They also sought ways to offset the expansion of American capitalism, which constituted a challenge for European markets. They therefore hoped to create a community based on the equality and full sovereignty of states, whilst simultaneously envisaging a European Tribunal, Customs and Monetary Union and a European aviation police force.

The ideas of the Pan-Europeans were taken up by a socialist politician and many-time French prime minister Aristide Briand. In 1929, he submitted to the League of Nations a proposal to create a European federation bound together by a community of economic interests.

But it was not the Pan-Europeans that inspired the first integration projects on the Old Continent. When discussing the concepts of Coudenhove-Kalergi and Briand in 1929, the leader of the Polish section of the Pan-European Movement, lawyer Aleksander Lednicki, recalled: “The Romans and Napoleon had wanted to unite Europe by the sword, the Church – through the Catholic faith, [Richard] Cobden [British politician and economist, advocate of economic liberalism] – by means of free trade, [Giuseppe] Mazzini [one of the leaders of the Italian Insurrection that erupted during the Springtime of nations] – through revolution, and Marx and Lenin – through communism”.

In that context, Lednicki would have also mentioned 19th-century thinker Teodor Korwin-Szymanowski, whose manifesto L'Avenir économique, social & politique en Europe (‘Europe’s Future in the Economic, Social & Political Realm’) written in French and published in Paris in 1885, has also appeared in the Polish Foreign Ministry’s Library of European Unity series.

The Polish squire was concerned about the turbulent situation of the Old Continent. Feudalism was being displaced by capitalist modernity, and social classes – by nations. Rebellious masses were rising to the fore. Korwin-Szymanowski, who was not particularly interested in the Polish question, believed that, in order to spare Europe (from) the catastrophic effects of revolutionary ferment, its elites must find a way to prevent dramatic social conflicts.

What titular future then did the author envisage? An International Bank should be set up on the Old Continent and given “the exclusive right to issue money in cash and securities. The European currency would be the franc, since it would be the easiest to introduce being already in use in many European countries and rather easy to liquidate in relation to other European currencies.”

To whom would the International Bank belong and whence would it obtain its financial resources? Korwin-Szymanowski indicated that its owners would be capitalist shareholders to whom the International Fund would belong. The International Bank would possess capital obtained by auctioning off real estate belonging to governments (but not to monarchs or royal families) i.e. “estates, farmlands, woodlands, factories, natural resources, etc.” as well as “proceeds coming from certain taxes such as customs tariffs, industrial taxes, etc.” Korwin-Szymanowski effectively sketched a vision that, especially as regards a common currency and customs union, was a precursor of the integration project being implemented today by contemporary Eurocrats.

Restricting sovereignty

Restricting sovereignty

By comparison, in the period between the two World Wars, the concept of a united Europe would have raised doubts owing to the conflict of interests dividing individual states of the Old Continent. Lawyer Władysław Leopold Jaworski, linked to conservative circles in Galicia [the Austrian partition], approached the matter bluntly: “Doubters ask whether now again the selfish interests of powerful forces are not hiding behind the slogan of putting an end to war and the slogan of protecting Europe from American hegemony. They wonder whether such noble thoughts simply disguise the bait meant to attract the weaker in order to all the more easily exploit them? But the powerful are also plagued by doubts.”

Jaworski then moved on to specifics: “The Germans were unrestrained, and the day after signing Locarno [the 1925 Locarno Treaty], one of its most outstanding politicians stated that they would not forego lands taken from them by the Treaty of Versailles. (…) Today words were spoken in the French chamber affirming the view that Locarno is meaningless as far as our security is concerned. And yet we had to sign it so as not to entrench the opinion of Poland as disrupting peace. Statesmen conducting world politics must time and again calm nations by thinking up some idea, creating some institution or signing some pact. Each such development is accompanied by a vocal expressions of hope that precisely this is the means of salvation. When that means ceases to function, a new one must be resorted to. The result is an illusory world that exists until it is destroyed by a disease so severe that no remedy works any more. The United States of Europe is the one means raising hopes for a better tomorrow.”

That painfully realistic approach at first glance stands in marked contrast to the views of nearly 93-year-old today émigré historian Piotr Wandycz. In a paper delivered in London in 1949 at the inaugural meeting of the British District of the Union of Polish Federalists, he openly stated that the integration project cannot be limited solely to the economic sphere. According to Wandycz, such a restriction was contained in Briand’s memorandum, and that is why the French prime minister’s proposal was a fiasco.

According to the historian, for the European integration project to succeed, states must agree to limit their sovereign rights, and economic integration must be followed by political integration. However, when reading the London paper, one gets the impression that Wandycz had envisaged the difficulties Europe would have to grapple with in the 21st century. In Wandycz’s words: “Federalism must encompass the broadest possible masses and prepare public opinion with which governments and political parties will have to reckon.” The Old Continent’s growing support for Euro-sceptical parties shows that did not take place.

Who is weakening the Old Continent?

Which forces presented and continue to present obstacles to European integration processes? In his 1963 book Polska i Nowa Europa (‘Poland & the New Europe’), a leading émigré commentator Aleksander Bregman referred to Charles de Gaulle as the principal villain. In launching the notion of a “Europe of states”, the French president effectively rejected the road to federation, and that in the author’s view ranked him among politicians weakening the Old Continent.

Simultaneously, he promoted the formula of “Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals”. He therefore extended his hand to the USSR: not so much to the then communist power, but rather to the non-communist Russia he imagined in the future. Bregman cited de Gaulle’s words: “regimes pass but nations remain”. According to the author, the French statesman was convinced that “the moment would come when that ‘rebelling daughter of Europe’ would return to the fold owing to the threat posed by China.”

But unlike de Gaulle, Bregman had no illusions about the Soviets. He cheered for Franco-German reconciliation and only regretted that, as a Soviet satellite, Poland could not take part in European integration. He realised a powerful Europe would have a far stronger position vis-à-vis the Kremlin and was convinced a divided and fragmented Europe served Soviet interests. He also felt a united Europe without Britain and devoid of US politico-military backing would become a “third force” between the Soviets and Anglo-Saxons capable of playing off the trans-oceanic power.

For that reason, Bregman wanted the United Kingdom to join the European Economic Community. He also sensed the anxiety felt by the British people over plans to create a European federation. At the same time, he bitterly realised that unlike Washington’s participation in global games, London showed little interest in the situation of Poland and other countries that found themselves in the eastern bloc.

That vision of the Old Continent’s erstwhile events calls to mind the situation we are currently witnessing. Is not the National Front under Marine Le Pen questioning the EU and Europe’s American presence whilst sending positive signals to Putin’s Russia a continuation of the de Gaulle legacy?

And didn’t the same tendencies observed in the United Kingdom 50 years ago re-emerge during the Brexit referendum? Has Russia finally changed its attitude towards Europe or does it want the European Union to be merely a toothless “third force” between Russia and the US?

One can paraphrase de Gaulle’s above-quoted words as: regimes collapse, but geopolitics remains in full swing. Jan Emil Skiwski was well aware of that. The émigré journalist was sentenced in absentia by the People’s Republic of Poland to life in prison for collaborating with the Third Reich. In 1943-1944, he was editor-in-chief of the Nazi propaganda gazette ‘Przełom’. As such, he had appealed to the Polish underground resistance movement to stop fighting German occupation forces, since it was the USSR that posed the greatest threat to the Polish nation.

One can paraphrase de Gaulle’s above-quoted words as: regimes collapse, but geopolitics remains in full swing. Jan Emil Skiwski was well aware of that. The émigré journalist was sentenced in absentia by the People’s Republic of Poland to life in prison for collaborating with the Third Reich. In 1943-1944, he was editor-in-chief of the Nazi propaganda gazette ‘Przełom’. As such, he had appealed to the Polish underground resistance movement to stop fighting German occupation forces, since it was the USSR that posed the greatest threat to the Polish nation.

After the Second World War, Skiwski openly voiced his support for a Polish-German alliance that would lay the groundwork for a future European federation. In an article titled Solidaryzm europejski (‘European Solidarity’), rejected by the Paris-based émigré journal “Kultura” and first published in 1999 by the periodical “Stańczyk”, he identified the Soviets and Anglo-Saxons as enemies of Poland. He regarded the USSR and USA as empires hostile to Christianity by virtue of being guided by the principles of materialism. He expressed the none-too-clear reservation that “America is a carrier or barbaric ideals whose only advantage over Soviet ones is that they are not pursued by means of mass murder and persecution.”

Unlike Bregman, Skiwski maintained that the US needed a united Europe only as a launching base against the Soviets. He contended that “such ad hoc consolidation could succeed in spite of Europe’s internal dissension. Fear of the Soviets could impose upon Europe superficial consolidation, leaving the embers of struggle hidden beneath the ash. And that state of affairs is advantageous to America, because it provides the key to the later shaping of Europe according to America’s, not our (European), needs and plans.”

Whereas one may disagree with Skiwski downplaying the differences between Russia and the US, he is right when he says the White House instrumentalises Europe. For quite some time now Poland has realised that Washington is not some good uncle defending the rights of nations and democracy but a power that uses lofty slogans to brutally promote its own interests. And it rarely ever repays the loyalty displayed by some remote Central European country.

As for a Polish-German alliance – perhaps it might stand a chance for success in a united Europe. Back in 1944, the philosopher and political scientist Feliks Gross, who was associated with the Polish Socialist Party, in his text Post-War Europe warned that such a model might enable Berlin to dominate the Old Continent. He suggested that only a consolidated Europe would be able to tame Germany.

If Gross turned out to be naïve, that was only because integration processes ran up against numerous obstacles of which the most important were the differences dividing the nations of Europe. Already in the inter-war period one heard the argument that nationalisms were straining Europe to the breaking point.

One may mention the French writer Julien Benda, the author of a well-known book titled Betrayal of the Clerks. He was described in the 1933 text Idea narodu europejskiego (‘The Idea of a European Nation’) by the Catholic thinker Karol Ludwik Koniński whose political sympathies leaned towards Poland’s National Democratic camp. He pointed out that, when disavowing the tribal mentality, Benda had affirmed the past of the Catholic Church as the institution that had united the Old Continent by means of Latin.

But in his conclusion Koniński exposed the pseudo-Christian character of the evidence Benda provided. The thinker explained that his evidence in an indeed Manichaeistic manner had placed specific nations in opposition to the Church, perceived as an abstraction. Koniński argued that the destruction of nations would also strike a blow at universal morality on which patriotism was based.

In his 1931 text titled Europa przeciw Ojczyznom (‘Europe against Homelands‘), the poet, writer and translator Józef Wittlin focused on the ideas of Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, another French writer. The intriguing thing was that this declared anti-Semite and enemy of rotten liberalism also condemned nationalism. He was later involved in collaboration with the Third Reich, only to subsequently become disenchanted when he realised Hitler had turned out to be a German nationalist rather than the builder of a European empire. After the victory of the anti-Nazi coalition, Drieu la Rochelle committed suicide.

It is understandable that the desire to purge Europe of nationalism stemmed from the will to prevent the slaughter and destruction of war. But if behind such intentions are attempts at social engineering and the domination of stronger states over weaker ones, as is now often the case, the results may be counterproductive.

Struggle for the new man

Struggle for the new man

Worth mentioning at this point is Karol Irzykowski’s 1925 work Paneuropa i hiperetyka (‘Pan-Europe & Hyper-Ethics‘). In it, the well-known literary critic picked to pieces the then young, barely 30-year-old Coudenhove-Kalergi. The titular hyper-ethics referred to the religion of the future advocated by the Austrian: a re-evaluated Christianity focusing on the return to nature and the pursuit of beauty rather than virtue.

Irzykowski patronisingly used Coudenhove-Kalergi’s young age to justify such views. But social engineering aimed at creating a new European, “liberated” from Christian “prejudice” and national “limitations”, is among the leading convictions of such fully mature contemporary politicians as Guy Verhofstadt and Daniel Cohn-Bendit.

The point is that such convictions are is clash with reality. Overcoming national “limitations” results in stronger nations dominating weaker ones. Amid the absence of Christian “prejudice”, axiological relativism comes to the fore. This in turn paves the way for forces capable of imposing on societies their perverse ideology (for instance “sexual and reproductive rights”) through the use of such persuasive slogans as “freedom” and “tolerance”.

As it clear to see, the battle for a united Europe has always also been a struggle over the concept of man. At present, that is perhaps the most important issue. Either a united Europe will be a Christian Europe of nations or it will cease to exist entirely.

Author: Filip Memches

Source: “Rzeczpospolita”

09.05.2017