Turkish peregrinations

In Poland, Turkey has always been an object of interest as a country that’s exotic but relatively close geographically. Do holidaymakers on the Turkish Riviera realize that the tradition of Polish travels to Turkey goes back 600 years?

Until recently, Turkey has been a destination for mass tourism from Poland. The conflict with the Islamic State could change this. Even so, we should remember that in the past even wars could not cause a complete freeze in Polish-Turkish relations. Orzeł i półksiężyc ('The Eagle & the Crescent'), a collection of accounts written by Poles who travelled to Turkey over the past 600 years that was published by the foreign ministry, bears witness to the great significance this country has in our culture, and to the curiosity Turkey has sparked among our travellers.

Until recently, Turkey has been a destination for mass tourism from Poland. The conflict with the Islamic State could change this. Even so, we should remember that in the past even wars could not cause a complete freeze in Polish-Turkish relations. Orzeł i półksiężyc ('The Eagle & the Crescent'), a collection of accounts written by Poles who travelled to Turkey over the past 600 years that was published by the foreign ministry, bears witness to the great significance this country has in our culture, and to the curiosity Turkey has sparked among our travellers.

An envoy held captive and a dead gyrfalcon

Between the 1699 peace treaty of Karlowice and the period of partitions, Poland and Turkey enjoyed peaceful relations. However, diplomatic ties between the countries predated those events and were maintained even during bloody conflicts. In peacetime Poles would travel to Turkey as envoys and spies, pilgrims and explorers, and in search of… work.

Luck was not on the side of envoy Gregory the Armenian in 1415 as he was setting out with Jakub Skarbek from Gora for the court of Mehmed I Çelebi. It was the first Polish diplomatic mission known to have reached the Ottoman court. King Władysław Jagiełło had tasked Gregory with brokering a truce between the sultan and Sigismund of Luxemburg, the king of Hungary and Germany. The sultan was well disposed towards the envoys, and agreed to a truce with the Hungarians. “He even repeatedly invited them to a common feast,” Jan Długosz wrote in his chronicles. Everything was going well for our envoy, up to a point. According to Długosz, the diplomat was “detained as a scout and enemy, and put in prison” by the count of Temessena (today Timișoara) while on his way home through Hungary. King Władysław Jagiełło was “deeply angered by the dishonour visited upon his envoy Gregory”. After much effort, the envoy was finally released and returned to Poland.

Our kings would often send Armenians living in Poland as envoys on account of their knowledge of the Turkish language and customs. At a time when Süleyman the Magnificent, better known today as a hero of the popular TV series The Magnificent Century, was winning his great victories, an Armenian called Wasyl Wrona and Jan Ludwikowski were sent on a mission to the Turkish ruler. Their principal, the Great Chancellor of the Crown Krzysztof Szydłowiecki, gave them a very difficult assignment. While doing their best to prevent Turkey from turning against Poland, they were supposed to find out the state of preparations for the sultan’s next expedition to Christian Europe. The envoys left for Istanbul carrying lavish gifts, among them a gyrfalcon, the largest species of falcon, valued as a hunting bird. However, not all the presents made it to the imperial capital.

“We hasten to advise Your Grace that the gyrfalcon perished after we had reached the banks of the Danube. But we took it along, for we want to show it to Ibrahim Pasha,” they wrote in distress to their chancellor. Luckily, the envoys safely delivered a falcon, a hawk, a hunting dog, and a Moscow drum, used as a lure for birds. “We ought to advise Your Grace that the Turkish emperor is greatly occupied in hatching designs on Christian lands,” they warned Szydłowiecki in the same letter.

A pilgrim, a poet & a physician

First published in Polish in 1607, Pamiętniki z pielgrzymki do Ziemi Świętej ('Memoirs of a Pilgrimage to the Holy Land') by Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł known as “the Orphan” became the primary source of information about the Middle East for readers in that time. The son of a Calvinist, Radziwiłł converted to Catholicism in 1570. While seriously ill in 1575, he vowed to go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In 1582, he made his way to Jerusalem and Egypt, then under Turkish rule. In his memoirs, Radziwiłł paints a vivid picture of the Ottoman provinces, and the life of the local people. For example, he recounts his visit to Ehda, a village populated by Arab Maronites, where the local patriarch “ordained one monk to the priesthood… The Host is of the same shape as the Catholic one… The patriarch offered us a meal of eggs, olives and butter, for they never eat meat,” he writes at the end of his description of the visit to the village. It should be added that after a Mass celebrated by a Maronite priest, the patriarch agreed to a “Mass for the pilgrims, read after the Catholic fashion, in an alb and a patriarch’s chasuble.” The pilgrims were under constant threat from roving bandits and soldiers setting out for war. Luckily, they were accompanied by a group of janissaries (paid for by Radziwiłł), but that didn’t always help. “The Orphan” was impressed by Damascus, “a very populous… and marvellous city.” Christians were banned from horse riding in the big cities of Turkey, and local Muslims were far from friendly. “As common people are oddly ill-disposed towards the Christians, the janissaries took us between them and we walked by the horses. Once the commoners saw us, they took to shouting and booing, especially lads, prompting others to pour out from every street to catch a glimpse of us. And when we went between the stalls, into more populous streets, they would pelt things and spit at us. Had it not been for the janissaries, we would have been torn to pieces.”

Sounds familiar? Radziwiłł marvels at many local customs. “Some pious men in those lands walk naked with their heads and beards shaven, in winter and summer alike. When I first saw such man in Damascus, I thought him a lunatic who had broken free of gaol.” He turned out to be a holly man who had renounced the world. “They wander through the city like beasts, helping themselves to whatever pleases them, be it bread or fruit for sale…” The pilgrim was particularly scandalized by Christian and Turkish stories of licentious holly men who allegedly “did it with fair ladies” in broad daylight. Vivid and well written, the memoirs of Krzysztof Radziwiłł the Orphan still make for fascinating reading.

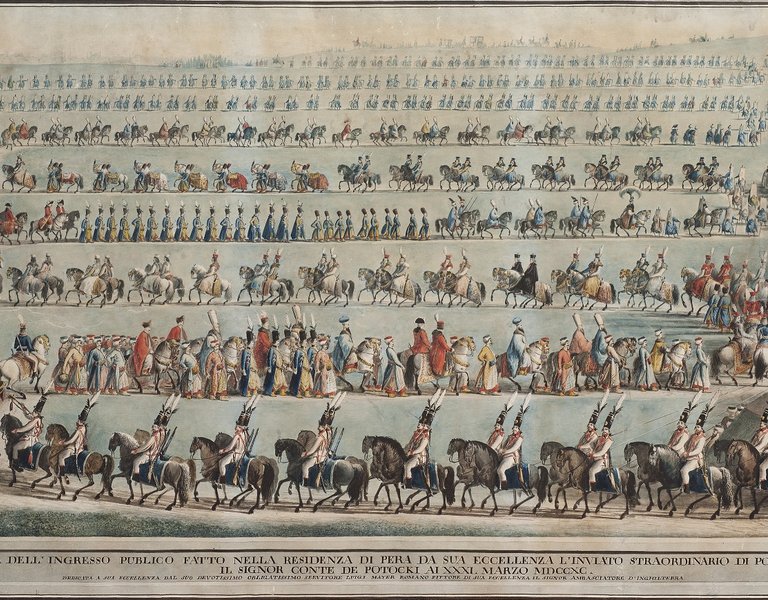

Samuel Twardowski, one of our most celebrated Baroque poets, went to Istanbul in 1622, as a secretary to Prince Krzysztof Zbaraski. Zbaraski’s mission was to negotiate a peace treaty following the Turkish retreat from Chocim in 1621. In his poem Przeważna legacyja Krzysztofa Zbaraskiego od Zygmunta III do Sułtana Mustafy ('The Important Legation of Krzysztof Zbaraski from Sigismund III to Sultan Mustafa', the poet not only reports on the difficult and at times dramatic negotiations, but also gives an insight into Turkish society and Islam. The latter he depicts as wrong and evil, the more so as the Muslims do not recognize Jesus’ divinity and do not believe in his death on the cross. He was struck by the slavishness of subjects towards the sultan. “The emperor is the sole master, the rest are slaves,” writes Twardowski, but adds that even a slave can earn high honours there, though often “…their downfall is but a step away, now robbed, now killed, all lost and vain.”

One hundred years after Twardowski, a Polish aristocrat called Salomea Pilsztyn née Rusiecka found herself in Istanbul. She must have been an exceptional and resourceful woman, having navigated her way through Turkey and its neighbouring Christian countries. She finished her memoirs, titled Proceder podróży i życia mego awantur ('My Life’s Travels & Adventures'), while in Istanbul in 1760. Aged 17, Salomea married Jakub Halpir, who set up his medical practice in Istanbul in the early 1730s. She learned medicine and ophthalmology from her husband, watched Turkish physicians at work, and studied folk medicine. Her story reads like a script for an action movie. Salomea’s husband won respect among Turkish elites. But that didn’t save him from prison after he was accused of causing the death of a wealthy patient. It was only thanks to his wife’s efforts, who bribed the right people, that his execution was stayed. In her memoirs, the self-appointed physician, whose good luck, intelligence, and keen sense of observation helped her cure several prominent figures, presents a colourful array of personalities she met in Istanbul and in other towns of Turkey. She also paints a compelling social picture of the elites and the hoi polloi. Her successes filled her rivals with envy, among them a pharmacist whom a certain pasha forced to give up his store on behalf of Salomea. “It was no small wonder that here, in Istanbul, where it hardly befits a woman to venture beyond her doorstep, I was allowed to sit in a pharmacy amongst such a multitude of people… For I was in great demand with people, what with my humane ways and best endeavours to perfect myself as a doctor and ophthalmologist. And thus people came to seek my medical advice…” Salomea recalled with pride. As a foreigner and a Catholic, she was able to stand her ground even before a sharia court, where she won a case against four Ottoman soldiers. Her son was one of the last residents of the Republic of Poland at the sultan’s court.

Author: Edward Kabiesz

Source: "Gość Niedzielny"

The European Unity Library (Biblioteka Jedności Europejskiej), under the patronage of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, is being published in interesting times. The consolidation of Polish membership of the European Union, changes in the euro area, the expansion of the Union, demographic processes, seismic shifts on the geopolitical map and dozens of other factors make for a fascinating world and continent.

The books to appear in this series will be devoted to the identity of Europe, its borders, its civilizational heritage, and its future. Outstanding authors from various academic and cultural backgrounds have been invited to work with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the impressive results of their work are now reaching readers.

26.09.2017