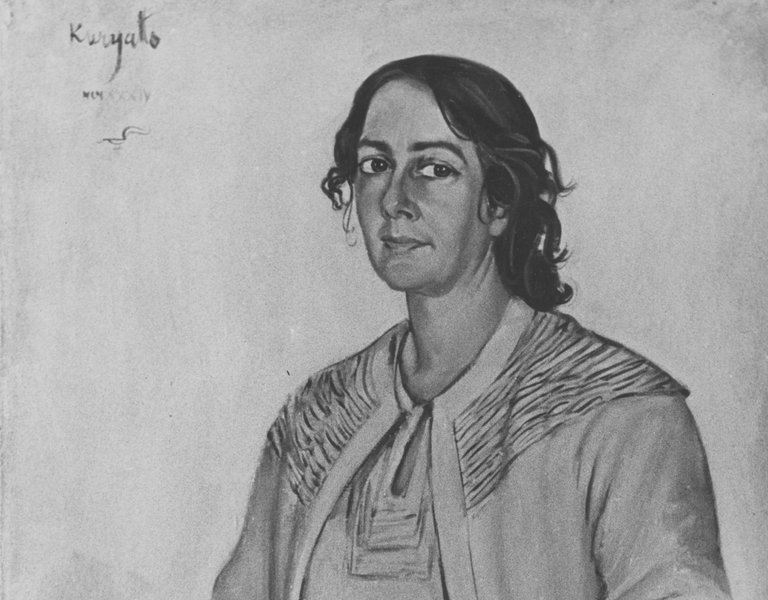

Zofia Kossak-Szczucka: An “anti-Semite” who saved Jews

During the war, Zofia Kossak-Szczucka saved hundreds of Jews, and after it ended refused to accept recognition of her literary achievements from the communist authorities. “I am a Catholic writer,” she proudly exclaimed.

“The world is viewing this crime, more horrible than anything else in the annals of mankind, and is silent,” Zofia Kossak-Szczucka wrote in an appeal to Western societies during the annihilation of Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto in August 1942.

“The slaughter of millions of defenceless people is taking place amid ominous general silence... That silence can no longer be tolerated... Whoever remains silent in the face of murder becomes the murderer's accomplice. Who does not condemn it, condones it,” she wrote.

The novelist, whose books have been translated into many languages, did not want to remain silent. During the war, she could not just stick to her literary efforts and the survival of her loved ones. Instead, she stood at the head of the Front for the Rebirth of Poland, a secret Catholic organisation. Soon thereafter, at the risk of her life, she co-founded an organisation whose purpose was to save and aid Jews (Żegota). She was sent to Auschwitz and did time at Warsaw's Pawiak prison with a death sentence hanging over her. After her release, she fought in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. When she returned to Poland in 1957 from an émigré's sojourn in England, she once again was unable to remain silent, although she was strongly urged to do so. Kossak-Szczucka, however, behaved as if she did not know what was what, as if she didn't know the rules of the game.

The comrades needed artists

The communist authorities tried to persuade the writer to write according to their rules. They did a great deal to have the writer, known for her uncompromising attitudes and attachment to religion, abandon thoughts of being the conscience of a Catholic nation. They wanted to see her amid the throng of writers applauding at Communist Party plena and sitting in the front rows at the regime's official assemblies. Even if they did not ardently praise the party like future Nobel laureates Czesław Miłosz and Wisława Szymborska and later sparred with communism (like Miłosz in The Captive Mind), they should at least combat Polish clericalism. Such services were rendered by Wisława Szymborska. “The first lady of Polish poetry” (together with Sławomir Mrożek and Jan Błoński) in 1953 added her signature to a manifesto signed by dozens of Kraków-based cultural representatives urging the communist authorities to bring forward the execution of imprisoned Kraków priests accused of “espionage and diversion for American money.”

Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, who came from the Kossak family of landowner painters, was unable to get involved in such declarations of servitude. “It's a known fact that honour is costly, and whoever has it must pay,” she wrote in a 1963 letter to friends. That was shortly after the rumpus she had raised after a newspaper falsely reported that she had attended a regime-sponsored writers’ meeting in Warsaw and had thrown her support behind the party. The following year she signed a protest against censorship (Letter of 34 in 1964).

The whole time the communists engaged in a subtle game with her. In 1945 she was forced to emigrate when given a choice of emigration or prison. She chose back-breaking work on an English farm. She did that for her husband Tadeusz Szatkowski. After leaving a German POW camp the pre-war Polish Army officer was suffering from depression. The couple and their two children lived on the peripheries of the highly politicised émigré circles and ran a small tenant sheep farm in Cornwall. It was decided after Stalin’s death that someone with such talent would be worth their weight in gold for the Party and their cooperation would lend credibility to the Party. The decision by Jakub Berman, the head of State Security Services, to banish the writer was therefore rescinded.

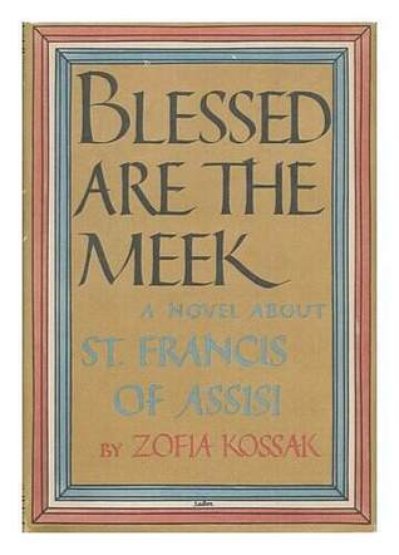

In the West, her novels made it onto the best-seller lists. Her 1937 novel Blessed Are the Meek was the Book of the Month in the United States. But in Poland all her writings were censored and were withdrawn from libraries and reading rooms. Her return to Poland unleashed great enthusiasm by her compatriots.

“You came at the right time. People are welcoming you, the land welcomes you, spring is in the air and the larks have returned. And here we have to roll up our sleeves and build at every turn, for there is such chaos in people's heads and in life,” a Kraków-based reader of Kossak-Szczucka wrote in a letter. She received hundreds of letters of welcome, and she herself expressed relief and joy at her return.

“We have always been like Pan Twardowski on the moon,” she wrote in one of her letters sent from England. “We are not threatened by disappointment. Good or bad – my country. I had been tormented by the awareness that our stay in Trossell was not in the service of Poland. Now we can serve.” She cut short the editorial admonitions of the London émigré weekly “Wiadomości” saying: “Everything that is Poland is good!”

I cannot accept this prize

The writer settled in the village of Górki Wielkie in the Beskid Mountain foothills, where she had lived with her family before the war. She busied herself with day-to-day affairs. Only ruins had remained of the Kossak family manor house burnt down in 1945. “The trees have grown like towers,” she wrote in one of her letters shortly after her return. “I wanted to kiss the threshold, but the entrance had overgrown with a blackthorn thicket.” Zofia and her husband Zygmunt lived in the former “gardener's cottage” of her family manor house, and each year had to ask the local council for a coal allotment to survive the winter.

Kossak-Szczucka tried to fight the censors who interfered even in her stories for children. She did not agree to censorship cuts in her volume Topsy & Lupus. When sharing her first impressions of Poland in correspondence with friends, she wrote: “We are still as if inebriated and confused in the whirlwind of welcoming. Two old savages, who hadn't had company in months, suddenly got transported into a cultured milieu and adulated. One can go mad.” But she did not go mad. She did not accept the First Degree State Prize awarded by the People's Authorities in June 1966 for her “outstanding achievements in the field of historical novels.” The award was not only an honorary distinction, but also included a sizeable monetary prize which could have easily enabled her to rebuild the family manor house. The award would have also made her a celebrity, fêted in the salons of communist Poland.

Following that incident, however, she had to reconcile herself to the thought that her literary work would get passed over in silence. In reply to the letter informing her of being awarded a prestigious prize, she wrote: “I cannot accept a prize from state authorities (…) that are hostile to what I hold sacred.” The prize “happened” to be awarded at the same time the icon of Our Lady of Częstochowa, on pilgrimage around the country as part of the Great Novena, was “arrested” (confiscated) by the regime. Observances of Poland's Christian Millennium were thus disrupted by events “insulting the cult of the Blessed Virgin, painfully wounding the hearts of Polish believers,” Kossak-Szczucka noted. “I am a Catholic writer who honours the Queen of Poland.” She dismissed the attempt to award the prize as a misunderstanding. Her books, withdrawn from book shops and libraries by the Stalinist authorities, once again found themselves on the index of forbidden works.

“If only other Catholics, tempted with prizes and distinctions, displayed such an attitude,” commented a clearly moved, Bishop Herbert Bednorz. Zofia Kossak's letter to the authorities was read out in churches all over Poland. When Primate Stefan Wyszyński read the letter at a meeting of the Episcopate, the hall burst into applause. Parish priests pasted copies of the letter at the entrance to their churches.

“...God would not demand it”

During the Nazi occupation years, the initiator of Żegota had displayed unbridled energy and resourcefulness in aiding Jews. She concealed them in her flat, sought out safe hiding places, smuggled them into convents and monasteries, provided them with falsified identity papers, supplied them with food and even dressed them.

She got hundreds of people involved in these activities. But during her lifetime she never received the title of Righteous Among Nations (it was bestowed posthumously in 1982). In the West, it was socialists and democrats who got the credit for Żegota.

She was arrested in September 1943 on a Warsaw street as ‘Frau Zofia Śliwińska’. There were Underground leaflets in her bag, but the Germans were unable to establish her true identity. She ended up in Pawiak prison and later in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where she came down with typhus. Before falling ill, she led common prayers and conducted literary chats. She also managed to get food and medication for the most needy. From Auschwitz, she got sent back to Pawiak prison for further interrogation, because eventually her true identity and links to the underground Home Army (AK) were discovered. She was able to leave only thanks to a huge amount of money raised by her underground friends. She described her stay at Auschwitz in the book Z otchłani (Out of the Abyss). Images of extermination were interwoven with reflections on the fortitude provided by faith, supernatural care in extreme conditions, the power of prayer by loved ones, the role of Angels and the tangibly felt presence there of Satan. Above her bunk in the barracks she scrawled in pencil: “In every moment of my life I believe, trust and love.”

She saw what had escaped the attention of concentration-camp chroniclers such as Tadeusz Borowski, the author of Farewell to Maria, and what failed to capture the interest Zofia Nałkowska, visiting a German camp shortly after the war and describing this experience in her Medallions. Those writers had focused on naturalistic descriptions of the German oppressors' sadism and an analysis of the demise of humanity in conditions of human debasement, planned with mathematical precision. But she, an outspoken Polish noblewoman, could not remain silent about the workings of Divine Providence even there. She wrote: “If enduring the camp was beyond one's strength, God would not have demanded it, because He knows what we are capable of. So, if He demands it, this means it can be endured... I believe, my God, that nothing will come in my way that, over the ages, You haven't predestined and sentenced me to and adapted to my strength (…) More than anywhere else, in a camp 'yes' should be 'yes' and 'no' should be 'no'. For we must not only accept and endure this evil, but also combat it.”

In her memoirs, she stopped short of quoting gutter language. She did not dare cite the exact words that female prison guards used when addressing inmates. She perceived her mission of a “servant of the word” in an old-fashion way.

After she had published her Auschwitz recollections, she was attacked by Tadeusz Borowski who accused her of graphomania, mythomania and a disregard for facts. The book could not have appealed to Borowski for whom Auschwitz had been the chief argument for losing one's faith. “She fantasises in nearly every sentence,” he wrote in his review of her book. “But she makes every effort to embellish her narration with abundant literary accents, and with her pretentiousness makes a macabre impression on the random reader who, by chance, had also been at Auschwitz. The errors of the author range from the verbal realm and run-away interpretations of facts all the way to absurd historiosophical notions. (…) Returning to Madam Kossak, I would concisely classify Out of the Abyss as a bad and false book which above all is literarily poor.”

Cognition and understanding

As an émigré, Zofia Kossak wrote A Mother's Image (Oblicze Matki), presenting a brief history of Poland, in which she declared: “Cognition and understanding – those are two truly human and truly Christian words. All crimes come from hatred. Hatred is nourished by imagination and simplistic notions about the presumed characteristics of some alien community. Cognition destroys such imagination and shows someone else as they really are.” In this way, she justified her lack of any feelings of enmity or any grievances towards Germans, Jews and Ukrainians. Shortly before her death, Zofia Kossak said her underground activities and stay in a German death camp, which she had survived thanks to prayer, love and sympathy towards people, were a gift and her life's greatest victory. Just as Father Maksymilian Kolbe stepped out of a rank of emaciated figures in striped prison garb and filled with dignity told the astonished Germans that he wanted to die in place of a fellow-prisoner, stating “I am a Catholic priest!”, Zofia Kossak was able to publicly tell the communists: “I am a Catholic writer!”.

Dozens of years after her death, accusations of anti-Semitism resurfaced. They came from circles that had turned the memory of the Holocaust into a new type of ideology or religion.

“That book is a masterpiece of nationalism,” was how historian Professor Carla Tonini of Bologna, specialising in the history of Poland and Polish-Jewish relations, described it in an interview: “The character of the female prisoners depends on their nationality. All the Polish women are heroines portrayed as courageous, God-fearing, comradely and never losing hope. Ukrainian, German and Jewish women are villains. They display weak personalities and are inclined towards improper behaviour.” In her writings, Tonini has clearly emphasised that Zofia Kossak was an “anti-Semite”, but “a strange one”, because she rescued Jews. “Contradiction is part of human nature. Many of Kossak's biographers presented her as a perfect, almost saintly individual. But this portrayal of Kossak is dull and boring. As a matter of fact, she was a fascinating character, human being made of flesh and blood,” the professor added patronisingly. If someone has been stamped with the worst possible epithet, they may be caressed a bit.

Anyone who was critical of Jews – and Zofia Kossak was, even in her Protest, in which she fought for aid to the Israeli nation in the name of Christian civilisation and culture, love of fellow-man and humanity – by definition could not be a good person. Such a person's nature contains a defective secret, a hideous stain that corrupts and makes him not the way he should be. Just as no-one who found himself in the hell of Auschwitz could be human, according to Tadeusz Borowski. They immediately became a worse person. If they pretended it was otherwise, they were lying.

The Order of Love is different from and superior to every other kind. The essence of sanctity is not found in the political, social or economic realm, as Vittorio Messori reminded. “But the workings of saints – although they transcend time and aspire to eternity – also have consequences in history.”

“We met during the (Warsaw) Uprising entirely by chance,” said Władysław Bartoszewski, who had been her secretary in 1942-1943, referring to Zofia Kossak. We embraced. I asked where Witold and Anna (Zofia's children) were and she said they were in the Old Town. I felt foolish, because the situation there was already quite dire. 'Have you had any information from them?' I asked. She replied: 'No, but they are in good care.' I foolishly asked: 'Whose?' 'God's' came her reply.”

Source: “Rzeczpospolita”

30.03.2017