Poland among leaders of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register

Poland can boast as many as fourteen valuable items on the Memory of the World Register, which gives our country a leading position in terms of the number of inscriptions. Among the listed heritage from Poland are the 21 Demands of Gdansk, a document from August 1980 that played a defining role in Poland’s regaining of freedom.

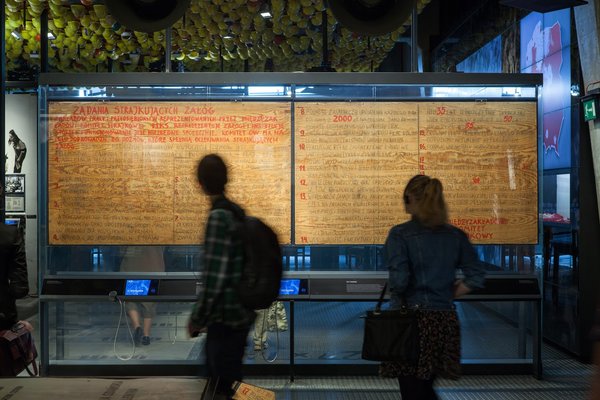

Each of the fourteen documents represents a different chapter of Polish history. The 21 Demands of Gdansk, written on a sheet of plywood and now kept at the National Maritime Museum in Gdansk, recount the Polish struggle against communism. “This is the most important symbolic document of has become known as August 1980, events that played a big role not only in Poland’s regaining of freedom, but also internationally, in overcoming the system of real socialism and the post-Yalta division of the world,” Tomasz Komorowski tells Polska.pl. Komorowski is a project coordinator at the Polish National Commission for UNESCO and belongs to the Polish National Memory of the World Committee. The Archive of Warsaw Reconstruction Office, kept at the State Archives of the Capital City of Warsaw, is in turn a source of information about the German occupation and the post-WWII reconstruction of Warsaw. The archive was inscribed on the Register in 2011 in recognition of its value as a documentary record of the destruction and subsequent rebuilding of Warsaw’s Old Town, something that came to be viewed as an international precedent.

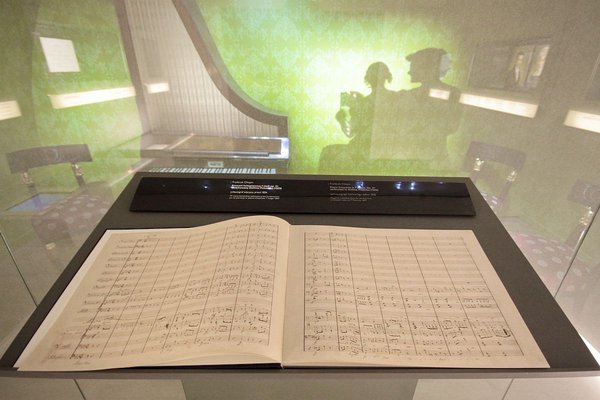

“Each of the Polish inscriptions is in some way especially interesting and important for appreciating the history of Poland, Polish society, and our place in Europe and world heritage,” says Tomasz Komorowski. It suffices to take a look at the first items on the Polish heritage list, which were entered in 1999: an autography (author’s manuscript) of De revolutionibus, Nicolaus Copernicus’ best known work kept by the Jagiellonian Library in Krakow; a unique collection of Fryderyk Chopin’s manuscripts housed at the National Library and the Fryderyk Chopin Institute; and the underground Warsaw Ghetto Archives (Ringelblum Archives) stored at the Jewish Historical Institute. Moreover, the Register features Codex Suprasliensis, an early 11th or even late 10th century collection of Christian Orthodox reading material for mass from Bulgaria, which includes the lives of saints and sermons of the Church Fathers. Written in the Cyrillic script, it is the oldest piece of documentary heritage kept in Poland to be inscribed on the Register. The Codex was originally discovered in the Basilian monastery of Supraśl in 1823. As Tomasz Komorowski points out, given its date of origin and volume, the book is one of the most valuable artifacts of the Old Church Slavonic language, and a major source for research on how Slavonic languages evolved in the early Middle Ages. As parts of the Codex are kept today in Poland (Zamojski collection of the National Library in Warsaw), Russia and Slovenia, it was submitted as a cross-border inscription.

With a total of 300 items, UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register features the most inscriptions from Germany (19). Poland has 14 items, followed by Great Britain and South Korea with 11 each. According to Tomasz Komorowski, the large number of Polish inscriptions is due to a high awareness of the importance of documentary heritage, and the need to preserve it. “Following the partitions and the Second World War in particular, Poland’s documentary heritage – archive materials, manuscripts, collections of books, photos, recordings, and films – suffered losses that are exceptional worldwide,” says Tomasz Komorowski. “Once you’ve experienced something like that, you are in a better position to understand how important it is to preserve and keep for future generations materials that enable you to study your collective and individual identity, and base your historical and cultural research on strong foundations,” adds Komorowski.

UNESCO inaugurated the Memory of the World programme in 1992 to improve the preservation of and access to documentary heritage the world over. Bringing together objects of special international importance, the Record is a means to that end. “This way the programme contributes to creating something that I think we could call ‘a memory of the world,’ i.e. a growing awareness of and familiarity with the historical experience of different societies and cultures, and their contribution to the common heritage of values and civilization achievements,” explains Tomasz Komorowski. The international Record is updated every two years at sessions of the programme’s International Advisory Committee.

AGATA NOWICKA

20.10.2015