Discovering Panufnik

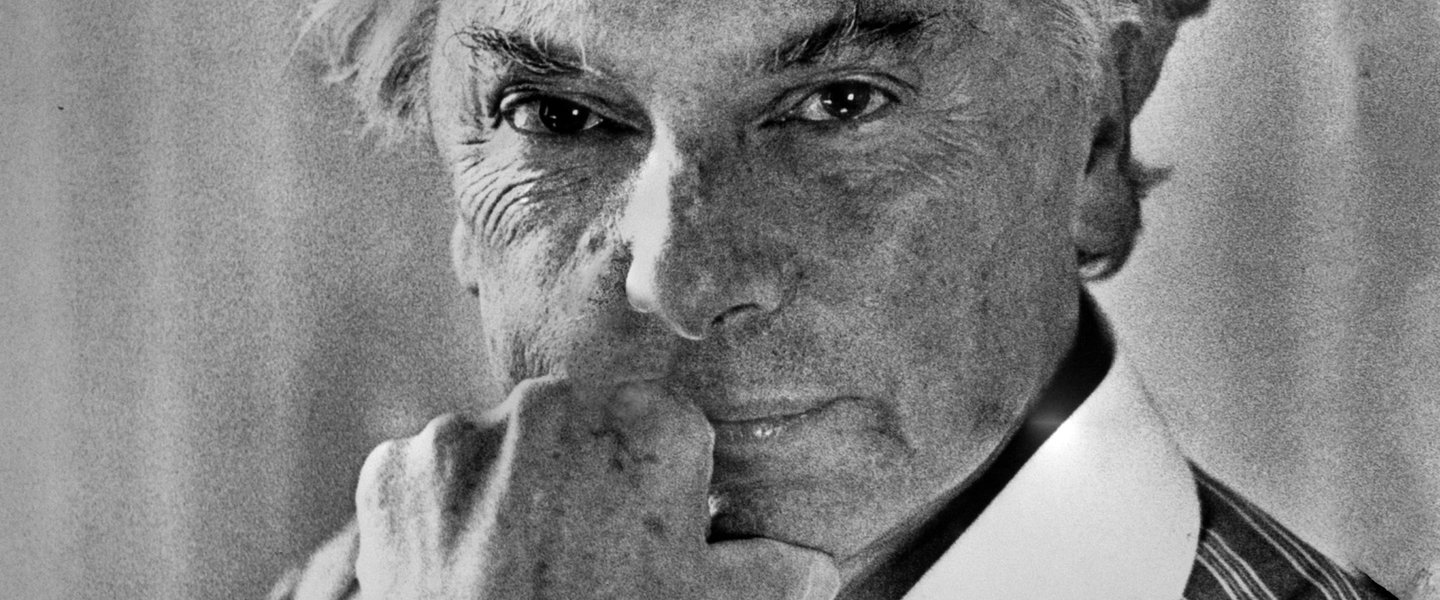

The Year of Andrzej Panufnik we are currently celebrating offers Polish listeners an opportunity to get to know a composer whom the communist regime treated as persona non grata since his defection to the UK in 1954.

“We, Warsaw children will fight for you, for every stone of yours, our City, we'll shed blood,” – the lyrics of the most popular song about the Warsaw Uprising immediately evoke its catchy, march-like tune. But few people realize that the melody was written by the Warsaw-born Andrzej Panufnik, one of Poland’s most outstanding composers, whose works often drew on the events of summer 1944.

The 100th birthday of Andrzej Panufnik is being marked both in Poland and Britain, where the composer spent most of his life. In his home country this is an opportunity to present his oeuvre to a wider audience. That’s because Andrzej Panufnik was unknown to Polish music lovers after 1954, the year he defected to the United Kingdom. The communist authorities made sure his records never reached listeners, it was forbidden for musicians to perform his pieces, and all references to the artist disappeared from books, encyclopaedias and official records. This was his punishment for betraying “the communist motherland.”

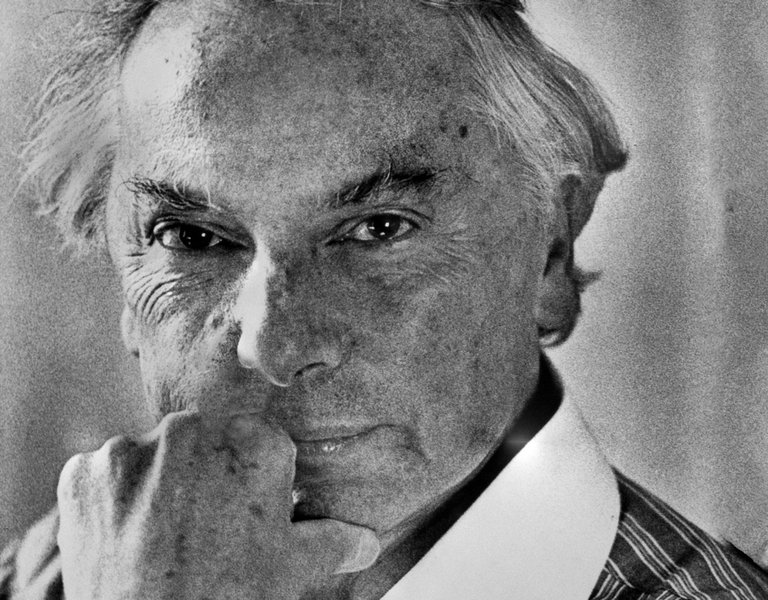

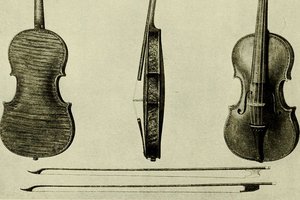

Born in Warsaw to Tadeusz, a violin-maker, and Mathilda Thones, a British-born violinist, Panufnik was a well-known figure in pre-WWII Warsaw. He authored hits performed by such celebrities as the Polish actor Adolf Dymsza. After graduating from the Warsaw Conservatory, Panufnik continued his studies at the Vienna Academy of Music, and went on to take private lessons in Paris and London. He returned to Poland shortly before World War Two broke out.

During the occupation Panufnik and his friend Witold Lutosławski, who would later become a world-class conductor in his own right, got by by giving concerts in the fashionable cafes of Warsaw: “Ziemiańska,” “Adria,” “U Aktorek,” and “Sztuka i Moda.” Their most successful piece was “’Paganini’ Variations” written by Lutosławski. Panufnik kept composing too – it was during the war that he finished “Tragic Overture,” whose score burnt in the uprising but was later restored from memory by the author. Panufnik’s brother, Mirosław, gave his life in the uprising; the composer managed to survive, having fled with his mother to the Warsaw suburb of Brwinów in July 1944.

After the war Panufnik became a leading representative of the young generation of composers. Pampered by the communist regime, he was also put under pressure. He was expected to write music that would tune in with the ideology of the new regime, i.e. conform to socialist realism and extol the new political system. Panufnik couldn’t come to terms with the new regime and would not allow anyone to tamper with his work. His relations with Lutosławski also cooled; we still don’t know exactly why.

Panufnik went from strength to strength. In 1946-47 he headed the re-established Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, and gave concerts abroad where he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, among others. Elected president of the Union of Polish Composers, he could meet composers of international renown.

But Panufnik was not comfortable with this political position, and would rebel against the official line imposed on art. His “Old Polish Suite,” “Nocturn” and “Sinfonia Rustica” were based on historical Polish music, which wasn’t to the regime’s liking.

In 1954 Panufnik ultimately decided to flee Poland. From Switzerland, where he had been invited as a composer, he asked for asylum in London. The London Times published his article about life behind the Iron Curtain. “This gentleman has disappeared,” was a saying about Panufnik that was making the rounds in Poland at the time.

The artist’s escape came as a shock to the Communist regime in Poland. Today we know that he was under security service surveillance for a number of years. It was only much later that the authorities calmed down, having realized that Panufnik was interested in artistic work rather than political activity. Before he came to lead some of Britain’s best orchestras, he conducted the City of Birmingham Symphonic Orchestra, among others.

His career flourished also thanks to his wife Camilla Jessel. Twenty years his junior, she was originally taken on by Panufnik to help him out with correspondence. The new Mrs Panufnik helped the musician overcome depression and encouraged him to walk his own path as a composer. The artist’s lack of enthusiasm for the avant-garde, which led to a conflict with the Communist authorities of Poland, also resulted in the BBC boycotting him for several years.

In the end, though, Panufnik came to be recognized by internationally celebrated conductors, such as Leopold Stokowski, who commissioned the “Universal Prayer,” Yehudi Menuhin (“Violin Concerto”) and Mścisław Rostropowicz (“Cello Concerto”). Panufnik was knighted by Queen Elisabeth II in 1991, and died the same year.

Panufnik’s children followed in their father’s footsteps. His world-renowned daughter Roxana Panufnik has been writing classical music, while the somewhat lesser known son Jeremy is a club music composer. In 2011, Jeremy made a film about his father entitled “My Father, the Iron Curtain and Me.” He wanted to confront Andrzej Panufnik’s legend and learn the truth about his life in Poland. The father would never discuss it with his son, and it was only from the mother, an Englishwoman who first came to Poland in 1991, that Jeremy heard about the composer’s home country.

“My father wouldn’t teach me Polish. I suppose he didn’t think we would need it one day. So I think of Poland as a fairy-tale land, a bit like my father’s studio with pinewood panelling and characteristic cutouts,” Jeremy (Jem) Panufnik says in the film.

To mark the composer’s centenary, the Institute of Music and Dance in cooperation with the Union of Polish Composers launched a special website dedicated to Panufnik’s oeuvre. The site features links to Ninateka, a music library of the National Audiovisual Institute.

On Ninateka.pl you can already listen to a premiere performance of “Two Composers, Four Hands,” a Roxana Panufnik composition dedicated to Witold Lutosławski and her father, as well as “’Paganini’ Variations” by Lutosławski.

KAROLINA KOWALSKA

27.09.2014