Everywhere is fun and interesting

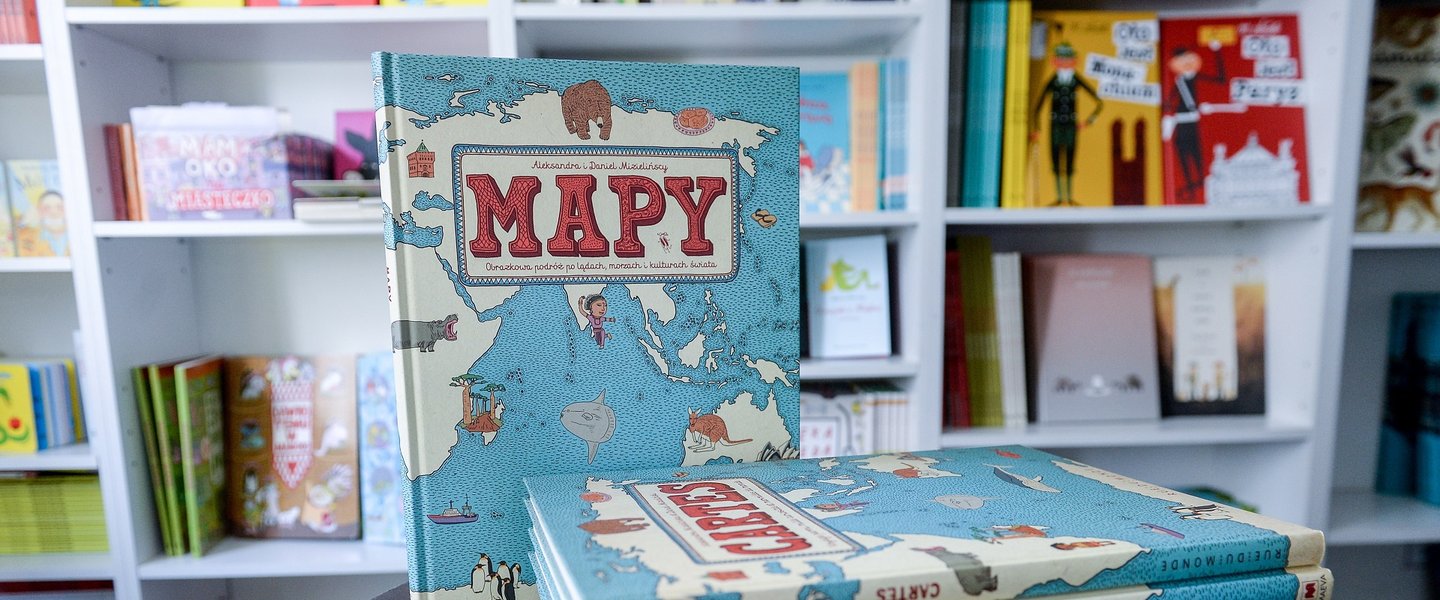

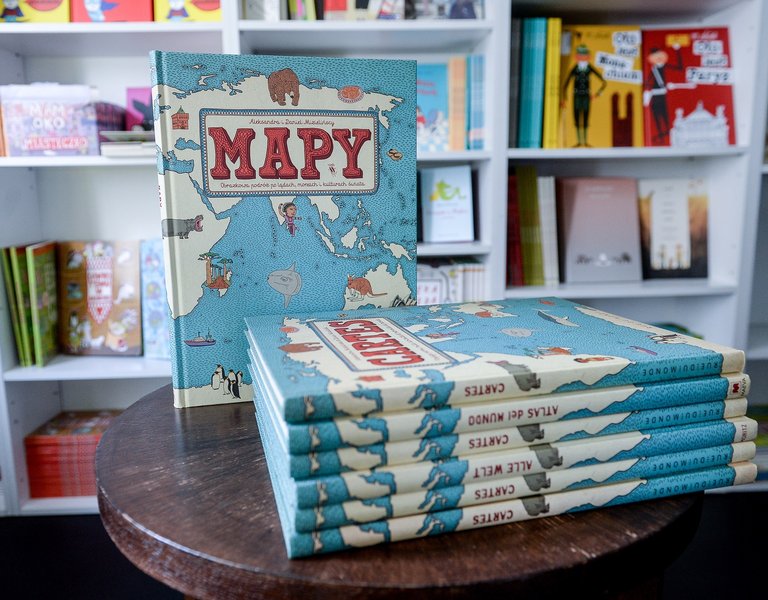

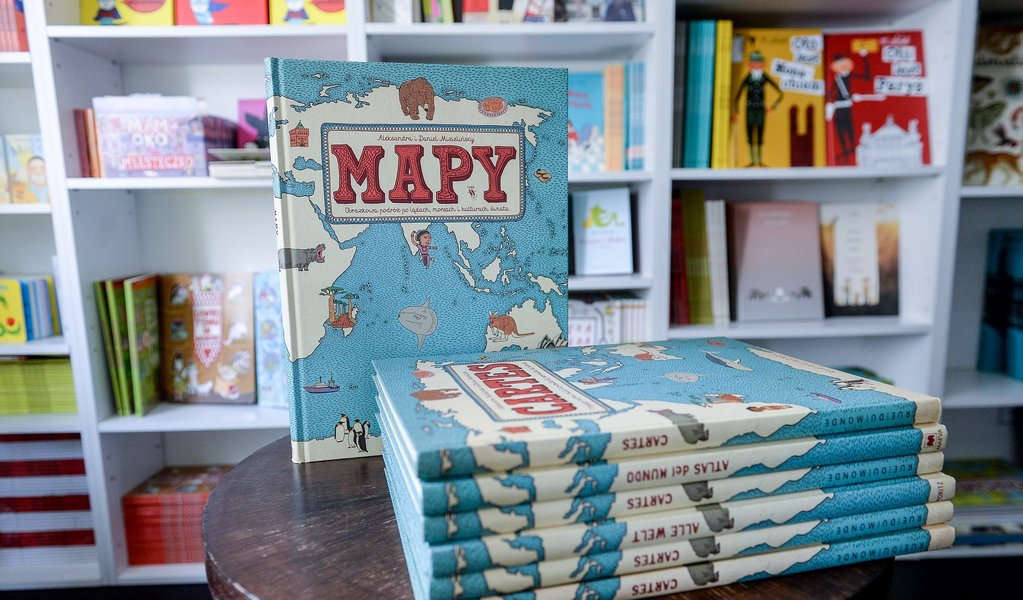

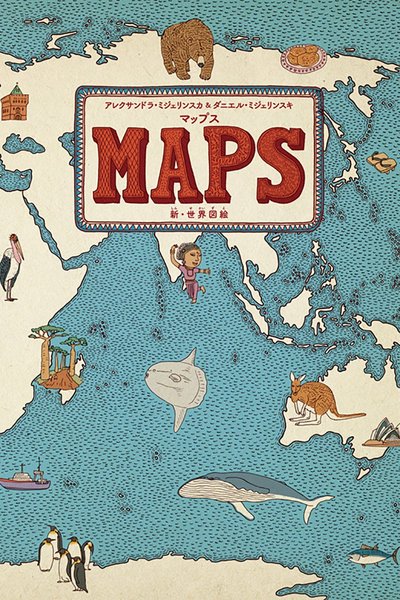

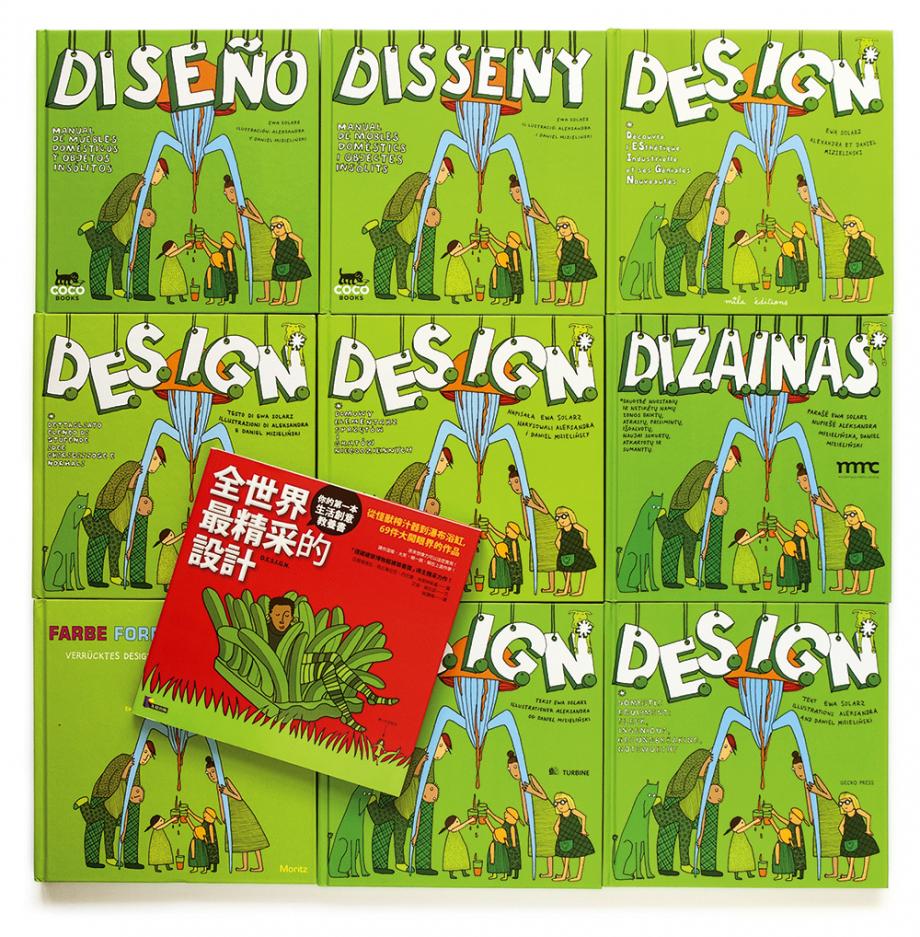

Prestigious, international awards. Millions of copies of books sold around the world and ... changing the format of shelves in bookstores. Aleksandra and Daniel Mizieliński have shown that books for children can literally conquer the world. We talk to Daniel Mizieliński about how the world translates into maps, and the Latin alphabet into kanji, why it is worth following Poland’s children's literature market and why programming is interesting for the artist. Together with his wife Aleksandra, Daniel Mizieliński has written and designed many beautiful projects – not only books, and not only for children.

POLAND.PL: In one of your interviews, you said: "Ideas are overestimated in our culture, everyone has ideas; Maps are difficult to call a super-idea – they have always been part of culture, this kind of map too.” And yet you have achieved worldwide success. Was this expected or surprising?

POLAND.PL: In one of your interviews, you said: "Ideas are overestimated in our culture, everyone has ideas; Maps are difficult to call a super-idea – they have always been part of culture, this kind of map too.” And yet you have achieved worldwide success. Was this expected or surprising?

DANIEL MIZIELIŃSKI: Success is never expected. We knew we had something with commercial potential, but the speed definitely surprised us.

You also said that "Maps can be liked because they refer to many things to which we have a sentimental connection.” From this it would appear that the key to creating a global phenomenon is to recreate what we already know. And yet, you create books for children, or "fresh" recipients of culture. How should one treat such recipients in order to get them interested in a book?

We do not think about the fact that we are creating books for children. We do not create them differently than we would do for adults. Sometimes, when we work on a book such as, for example, Here We Are, where there is a difficult nomenclature and the knowledge of the basics of physics must be understood, we wonder how much we must explain words that go beyond the level of education of children towards whom the book is targeted. However, for 90% of parents, the contents of the book, like Art, which Sebastian Cichocki wrote, or Music, will be as new to them as it is for the children.

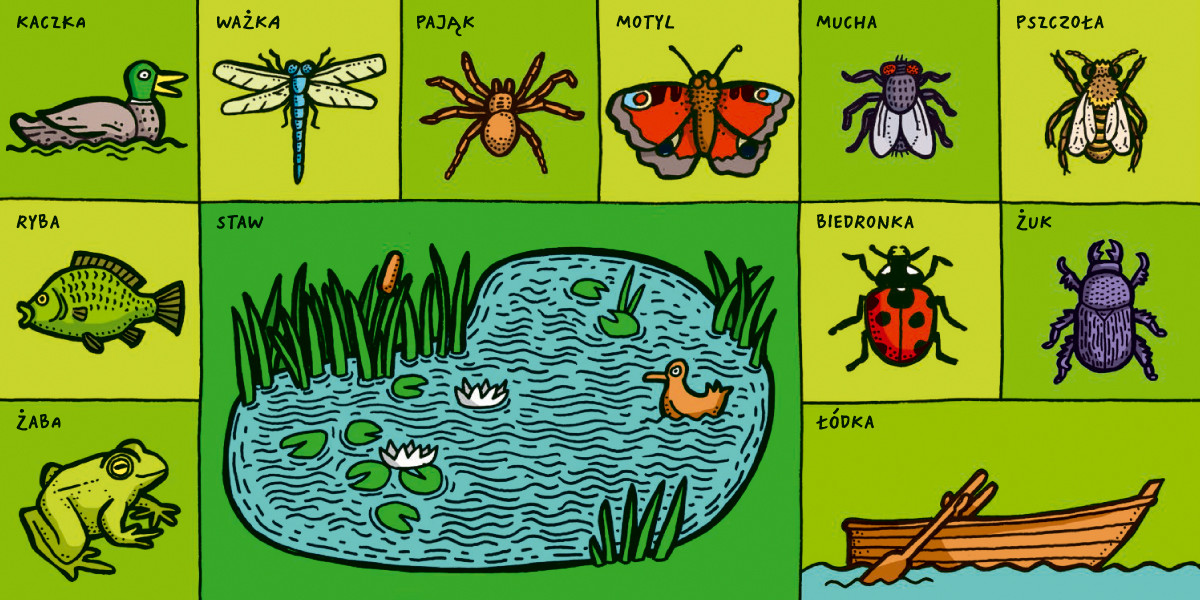

A book targeted at the youngest recipients is One Day – an illustrated dictionary, showing the times of the day in the life of a one year old child. How is such a book created if the perception of such a small child is completely different from that of an adult?

This is a book that we did during a break from large books – for some of them, we have 150 pages of research for one or two spreads, which shows how exhausting working on them is. We saw that there was a gap on the market – all similar picture books were deemed to be very poor, because they were based on pictures from generally accessible databases, in effect tacky, poorly produced images. And the need for such a publication is obvious - and at the stage of 10 months, when the child does not speak yet, but he/she is able to point to objects, and we are able to read to them and make sure it sticks; and later, when the child starts to pronounce syllables and can assign some names to objects.

I will not ask about where you get your inspiration from, because it seems that the whole world is your inspiration. But I do want to ask how is the choice made? In asking that, I have the best-selling Maps in mind: how does one choose 50 countries from almost 200? How do you choose these animals and not others? Or dishes?

I will not ask about where you get your inspiration from, because it seems that the whole world is your inspiration. But I do want to ask how is the choice made? In asking that, I have the best-selling Maps in mind: how does one choose 50 countries from almost 200? How do you choose these animals and not others? Or dishes?

The selection of countries is of course the most controversial. The truth is that this book would never have been created if we had not been subjective in choosing certain countries and not others. There is a lot of controversy around this choice today. As you can see, we, people, are already programmed so that the nationalist trend must resonate for us even in a book for children, which by design is supposed to show that everything is fun and interesting. For example, we received several hundred e-mails with questions about why Portugal is not available in the first version ... But it is already. We are actually working on this book every day, to this day, because we are constantly preparing foreign editions (Dutch and Icelandic versions at the moment) and we are gradually updating other editions, so the extended edition contains Portugal.

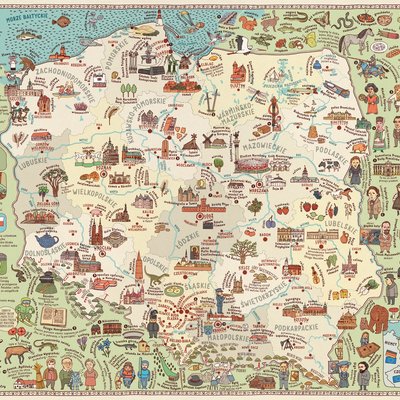

Our goal was not to set the final boundaries of the world. We used the following method: each country where the book is published uses the borders recognised by that country. As for the choice of other things - such as food, plants, animals – this is a very interesting process, although the guiding theme is not always the same. Sometimes we want certain elements to be repetitive, for example, the brown bear is used in several countries, and sometimes we present exceptional specimens. Not everyone has warmed to this - a publisher was irritated about why we chose to depict a mantis in his country…And it was a really impressive mantis.

Strength of associations ...

Yes. In such situations, we do not change our choices. When creating each map our starting point always consists of research, which makes up the lion's share of our work. First, we make a note of 200-300 elements that could potentially be found on the map: they fit the key, they can be presented well. We choose about fifty of them, we put them on the map. We make consultations when it comes to famous people. It is worth noting that these additional maps are currently being created for the needs of a specific edition. This gives us comfort because we have direct contact with a resident of a given country, so we can confirm our choices. Interestingly, often publishers suggest quite stereotypical characters that are completely uninspiring to children. There are not many captions in Maps – that's why the characteristics must be condensed and easily defined. If we simply write ‘politician’ on the side, then although this may be a very influential person, their activity can be completely understood by people from outside, not only for children but also adults.

Are your books created with foreign editions already in mind? You have already spoken about Maps, but when I look at your work, for example, the series about Mamoko, which seemed quite universal, in Mamoko the letters and Mamoko the numbers suggest that they were designed with the English or French market in mind. Am I right?

When we started working on Mamoko, we did not think about the fact that we could be published abroad. However, the two little books you are talking about were in fact made later. Letters was created in such a way that we wrote out the lists of words in 7 languages and the created drawings based on them. Thanks to this, it was enough to replace the numbers and the book could already function in a specific market. In Numbers, we did not have to change anything.

As for other titles – we do not make books with a specifically Polish or English children in mind. In fact, there are Polish elements in each of them – although we do not do anything by force, they just are there. But we do consider how we can make our work easier to implement from a technical and production perspective if it later ends up being translated.

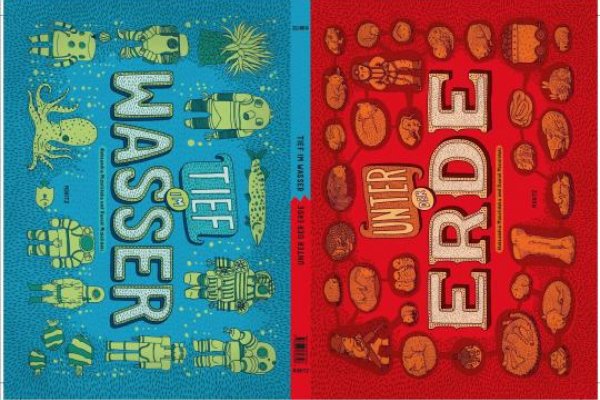

Our books are difficult to type set – that's why, for example in Underwater, Underground, we have already tried to simplify this aspect. We, of course, check and accept every page of each edition.

Do you design the fonts yourself?

Yes. And Maps, and all other books are published with our typefaces. In principle, we limit ourselves to our own type faces or the work of Michał Jarociński.

The list of your type faces is really very rich. How do you deal with translating these Latin typefaces into other alphabets?

This is a quite complicated process. Some of our fonts contain characters used in other languages, for example Cyrillic or Greek characters. But Chinese, Taiwanese, Japanese and Korean editions must be based on the choice of typefaces. Publishers suggest something to us – we try to make this choice reflect the weight differences of the fonts used in the original projects. We explain that what these typefaces are meant to be associate with, for example the handwriting that children learn at school.

Additionally – this book is designed to look dense If we suddenly translate it into Chinese, where instead of a dozen or so Latin characters, there are three square characters with a completely different structure, then this book begins to look completely different. In that case we have to arrange something differently, changing the typeface. And still the Chinese edition is lighter. The prototype in the Japanese edition was easier to create. In addition to kanji - Chinese characters that carry meanings for whole words, ideas or concepts - hiragana has also been used, applied to record sounds that are needed with regard to grammar or the entire text, if the text is intended for young children. There is also furigana - tiny hiragana characters, which are put on less-used kanji signs. This is done to avoid problems with their interpretation, and in the case of children's books they accompany every kanji.

Additionally – this book is designed to look dense If we suddenly translate it into Chinese, where instead of a dozen or so Latin characters, there are three square characters with a completely different structure, then this book begins to look completely different. In that case we have to arrange something differently, changing the typeface. And still the Chinese edition is lighter. The prototype in the Japanese edition was easier to create. In addition to kanji - Chinese characters that carry meanings for whole words, ideas or concepts - hiragana has also been used, applied to record sounds that are needed with regard to grammar or the entire text, if the text is intended for young children. There is also furigana - tiny hiragana characters, which are put on less-used kanji signs. This is done to avoid problems with their interpretation, and in the case of children's books they accompany every kanji.

We also had a large problem with the Georgian edition, because the local typographic culture is rather modest as a result of economic and historical reasons, and because these characters only appear there. That is why matching the typefaces to this edition has been going on for a very long time. Completely different characters are also used in the Thai edition.

We do not think about ourselves only as illustrators, but as creators of the whole book. We consider typography as a kind of illustration that gives character to the whole. Therefore, works on foreign editions are continuous puzzles. We do not adjust too much when it comes to content. When working on a project we always keep in the back of our minds the thought that the book will be widely published. We try not to take on topics that are very local.

And cultural differences? Do you think about them?

We are aware of them. But when I personally as a recipient am looking for a book from Korea, I do not want this Korea to be filtered by a Polish publisher. I want to receive what the author actually did. Therefore, we assume that people who reach for our books are curious about what is being created here in Poland. We do not make books only for Poles, but we ourselves come from Poland, we have been brought up in Poland, all our experience, all of our education and what we do originates here. And despite traveling, discovering and being interested in other places, we will not change who we are. To be sure, our books are influenced by the Polish children's literature genre. We want them to be like that. May the cultural differences remain. Although we try to be sensitive to them, do not insult anyone. It's important to us that our books really are for everyone. That everyone will find something for themselves in them.

Allow me to return to this "Polish" framework. I know that the map of Poland was created first. The choice of content, finally placed on this map, was more difficult or easier than on others?

Allow me to return to this "Polish" framework. I know that the map of Poland was created first. The choice of content, finally placed on this map, was more difficult or easier than on others?

It was both easy and difficult. Always creating the first spreads is the most difficult and we often come back to them to adapt to what the book has become. The map of Poland – in my opinion – is completely different from the others. Animals, trees and the objects on them are all drawn differently. It is only with the publication of the third edition - after the addition of Skłodowska-Curie, Szymborska and Lem - that the map contains everything it should have had in the first place. The analysis was easier in this case – although of course some information surprised us, because Poland, for historical reasons, is very regional and the borders of the former partitions still mark the sphere of influence. Poland and the United States – these spreads were the easiest for us, due to access to information. On the Internet one is able to find everything about the United States, and we've been there many times. Information on Poland – if only because we can search for information in Polish – is also easier to compile for us. The hardest part was for us to prepare maps of those countries in which there is relatively little tourism and about which not much information is widely available.

Was the D.O.M.E.K. book supposed to be an answer to a certain architectural chaos that Poland is accused of?

It was our debut. We went to a publishing house with several books written and designed by us. The publisher suggested us to create a book about architecture. This was not the answer to what is happening in Poland, but to the gap in the market at the time. At the time, non-fiction for children did not exist, although we had a wonderful tradition. In the 1990s, this trend deteriorated - it was a terrible time for the children's book genre - and at the beginning of 2000, thinking about illustration staged a comeback and once again became something important. At that time, we did not know more about architecture than average students who graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts. However, we wanted to show that houses can be very different, have different functions, and the architecture as art is very diverse.

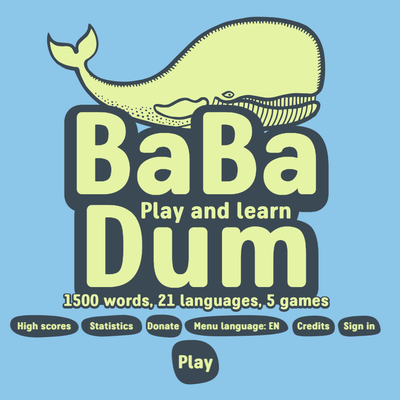

We are talking about books, but you do not only do books. Babadum.com, for example, is a platform with visually pleasing and fun games, thanks to which both children and adults can learn foreign languages. How did this project come about? And what do new technologies give to educational projects, such as this one?

For me, programming is the most interesting form of creative work, much more interesting than illustrating. Technology gives us unprecedented opportunities to reach hundreds of thousands of people in a day! We cannot react instantaneously to what the reader of the book is doing. And with Babadum we can act immediately. BaBaDum combines this joy with what we were after. One of our books was a picture dictionary with captions in 6 languages. BaBaDum evolved from this gradually.

For me, programming is the most interesting form of creative work, much more interesting than illustrating. Technology gives us unprecedented opportunities to reach hundreds of thousands of people in a day! We cannot react instantaneously to what the reader of the book is doing. And with Babadum we can act immediately. BaBaDum combines this joy with what we were after. One of our books was a picture dictionary with captions in 6 languages. BaBaDum evolved from this gradually.

What is annoying with regard to the creation of games is their fleetingness. Something we did 10 years ago does not work anymore. We would have to write it from scratch. Knowing more, we are now trying to create these projects so that they have a longer shelf life. By using web standards, you can do a lot. When teaching game design at the Academy, I am not able to relay the history in its full entirety. Some key games cannot be played as there is no way to do so.

The Pica Pic project [Pica Pic is a portal where you can play digitised hand games from the 90s – Poland.pl] was supposed to serve as the archive of old games – but we did it using now dead technology and now we would have to rewrite this page.

Games are not like music or books, where it is enough to change the medium. King’s The Shining will be read in the same way as it once was. It's different with technologies. Even when renewed games are known from the past, many things change in them so that modern players do not have to adapt to the realities of playing the game from many years ago. However, creating something in an unlimited world, neither with paper, nor anything, is a pleasure.

A huge number of awards ... a place on "The New York Times” book list - a list of the best books for children. Over a million copies sold in China ... Your achievements and you yourselves are the ambassadors of Poland in the world. Do you sometimes think about yourself in such categories?

I do not think so. Of course, it's great when you travel around the world and see your books in all sorts of places, but it did not happen all of a sudden. What is happening is associated with a huge amount of work and maybe because when I see our book somewhere in a bookshop at the end of the world, I immediately see things through a practical perspective: I am reminded of what we were facing, I check how it turned out. A type of quality control.

But it happens that I see our books in the strangest of places. I once saw a well-known Youtuber telling viewers where she traveled as a child. And she was showing these places on our Maps! In such moments I actually feel: We have arrived! When I see our work in really surprising contexts for the book. Or when we see plagiarised copies. Another case in point is the fact that after we insisted on this format – which was strongly discouraged due to the size of standard bookcase shelves – these shelves in fact have been adapted in many places. The standard has been introduced in exactly this format, and probably every major European publisher now offers exactly this size of the book.

But it happens that I see our books in the strangest of places. I once saw a well-known Youtuber telling viewers where she traveled as a child. And she was showing these places on our Maps! In such moments I actually feel: We have arrived! When I see our work in really surprising contexts for the book. Or when we see plagiarised copies. Another case in point is the fact that after we insisted on this format – which was strongly discouraged due to the size of standard bookcase shelves – these shelves in fact have been adapted in many places. The standard has been introduced in exactly this format, and probably every major European publisher now offers exactly this size of the book.

We have discussed the Polish market of children's literature - how much has changed in recent years compared to the times when we were children. I am curious if there is something on the Polish market, which you yourself like to watch - alone or with children - and that you can recommend.

Sure! We've been collecting books and comics for years. There is a lot going on in the market. It is a bit worse with Polish comic books, but it is worth recommending the Fairytale at the End of the World, Magic Garden and Abandoned House. It was made by Marcin Podolec. This is one of the best things I've seen in a long time!

When it comes to books – we like basically everything that Dwie Siosty (Two Sisters) publish – I say this not because this is our publisher, but because it is largely our philosophy that coincides with their vision. It so happened that in Poland all good art colleges offering courses on book design, also cover children's books. The creators of the Polish poster school also did it. It is somehow in our blood. And yet despite this tradition, when it comes to text writing the success rate is more varied.

At the beginning of the 2000s, when there was nothing, there was full freedom. Now the market becoming more saturated, which also creates challenges. You can see that people some involuntarily take over certain characteristic features of what has been created so far – I do not mean strictly speaking imitation, because that is also there, but it is a different topic.

We see that there a strong aesthetic trend has emerged – which may even be a pity, because there are many techniques, such as more realistic illustrations, but also areas, such as this unfortunate comic book, which is completely undeveloped. And the potential is there! Maybe it's the fault of publishers and distributors of comics? Comic book publishers do not actually print picture books, and picture book publishers do not print comic books. Therefore, even in bookstores there is either one or the other, despite the fact that these two worlds are very similar. In the meantime, there are many people at the Academy who would like to do comics and do a great job making them.

These days non-fiction is popular and that is probably why so many things are being published that are not properly thought through, not fully conceptualised or discussed. They contain all the information there is and as a result do no encourage readers to discover a specific academic area.

These days non-fiction is popular and that is probably why so many things are being published that are not properly thought through, not fully conceptualised or discussed. They contain all the information there is and as a result do no encourage readers to discover a specific academic area.

There is a lot of interesting things happening in the fiction genre, much like in the activity books section, which have also become extremely popular. There are plenty of books for children, something that has been confirmed by the fact that there are queues to Polish stands at all international fairs. I hope that this diversity in the Polish book market will not end, although I must warn that I have the impression that some Polish big publishers have already focused only on what works – not even specific books, but certain formats. They pick and create alternatives. And there are a lot of authors that have a lot of ideas that they are able to develop, which is something we see in the competitions.

You travel a lot. Is there still a place that you want to go but haven’t yet had the opportunity to visit?

When we were in college and getting ready for the first trip, we wanted to choose between the United States and Japan. The US won and from that time we returned every year, also with small children, despite the obvious difficulties of such a long journey with little twins. However, we have not yet been to Japan or South Korea. We will definitely head out there when the children are older.

And finally the question we ask all of our Poland.pl interviewers: what do you like most about Poland?

This is what we recommended in Maps. We are currently working on another book, thanks to which we are discovering even more interesting cultural trails. It's difficult to choose one thing. When it comes to books – my favourite writer is Lem. As for illustrations: Butenko – what he did will be universal for a long time. What he did decades ago is now being discovered.

Poland.pl

22.06.2018