The Horned Heart

He was a source of inspiration for the rock group Tool and a mentor to Leonardo DiCaprio. It is 30 years since the passing of the outstanding Polish sculptor and art theorist Stanisław Szukalski. His biographer, Prof. Lechosław Lameński from the Catholic University of Lublin, told Poland.pl why “Stach from Warta” has once again become fashionable in Poland and the United States.

Poland.pl: Who was "Stach from Warta"? Looking back, how do we evaluate his place in the history of Polish contemporary art?

Lechosław Lameński: Stanisław Szukalski was certainly one of the most outstanding Polish artists of the twentieth century. Today he is somewhat forgotten also because he practically spent his entire life in the United States, although paradoxically his greatest artistic achievements were accomplished during his short and some longer stays in Poland in the 1920s and 1930s. It was a time of magnificent exhibitions and even more magnificent plans that were never realized due to the great fancifulness and unrestrained temperament of their author. However, the long-forgotten Szukalski managed to make a comeback and from the 1970s once again became an artist, one about whom people talk about, whose exhibitions and work attract astronomically high prices at modern art auctions. I know that there are plans for large exhibitions dedicated to Stach from Warta in the National Museums in Krakow and Warsaw, and now his works can be seen at the exhibition of Late Polishness at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw.

What had a bigger impact on his artistic education - the Chicago Art Institute or his unfinished studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow?

What had a bigger impact on his artistic education - the Chicago Art Institute or his unfinished studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow?

I think that the school in Chicago and the key years 1913-1923 played the biggest role, during which he became a central figure of artistic Chicago. His strong personality and unconventional behaviour, along with his very interesting sculptures, helped him win the hearts of the American public. His four years of studies in Krakow gave him a serious practical foundation, which he used in later works, but the Chicago period was the most important, then was when his artistic views, including those associated with the affirmation of Polish art, were supposed to guide the art of the whole world.

The 1920s actually saw an incredible boom for Szukalski in the United States. “Vanity Fair” wrote that he was for sculpture what Dante Alighieri and Edgar Allan Poe were for literature …

He was an extremely charismatic figure, he had a gift for speaking, shocking people with his appearance, with his long hair, specially designed clothes. He was a strong personality, and at the same time he brought to Chicago a wave of European art showing that it was possible to create irresistible styles without paying attention to the critics. When he returned to the United States again in 1939, he was not able to repeat those successes - many changes and breakthroughs had since taken place in the modern art world, and in his art he remained true to his style but was undervalued by the critics. In the meantime, he was also very successful in Poland, and probably if it weren’t for the German and Soviet aggression of 1939, Poland would be filled with monuments designed by Szukalski and in Krakow, as a counterweight to the "fossilized" Academy of Fine Arts, there would be his “Twórcownia”, that is a studio for Szukalski and his students.

From the very beginning, Szukalski’s work and his attitude sparked controversy. Was it a question of his character or were his skirmishes premeditated? Or perhaps the result of the onset of mental illness, which had already been attributed to him at the time?

From the very beginning, Szukalski’s work and his attitude sparked controversy. Was it a question of his character or were his skirmishes premeditated? Or perhaps the result of the onset of mental illness, which had already been attributed to him at the time?

I think it was a combination of all three factors. He was undoubtedly a strong personality, consciously building around him an incredible artistic atmosphere, which, judging from reviews, was liked by some and disliked by others. He had a difficult and complicated character, he did not like interference and admonitions. When a Chicago critic unintentionally touched one of his works of art with his cane, Szukalski broke the cane and kicked him out of the apartment. And there is also the issue of mental illness, schizophrenia, which began to be identified in the 1930s, gaining momentum at the end of his life.

Stanislaw Szukalski left Poland just before the German aggression. What happened to him after that?

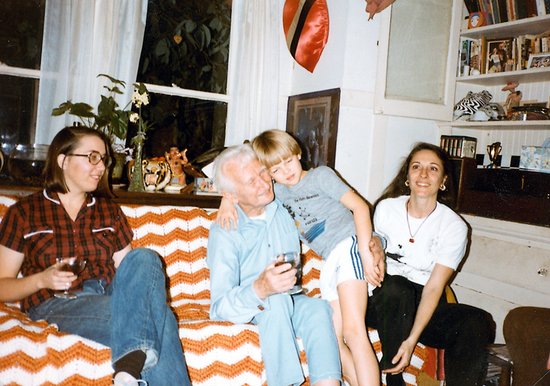

In my opinion, this was the least successful period in his life, perhaps because of the aforementioned schizophrenia, or perhaps because he took on non-art related projects, such as Protong's theories as linguistic and ethnographic studies, which led him to say that in the beginning, in prehistoric times, people spoke in one language and it was Polish (!). His works of art from this period are no longer as innovative and inspirational as the work created by Stach from Warta pre-1939. In addition, he lived in poverty while residing in California, he was employed in various professions, also related to the film industry, but greater money and comfort both remained elusive for him. He divorced his wife, and his difficult character practically led him to isolation, also in artistic life. It was not until the early 1970's that he came across Glenn Bray and Lena Zwalve, who founded the stalwart Szukalski Archive, and organized his first exhibitions after a long hiatus.

It is difficult to overlook the controversial themes of Szukalski’s life. His writings reveal evident anti-Semitic and anti-Christian undertones and fascination with Italian totalism. On the other hand, Norbert Strassberg – the son of a Jewish tailor from Lvov – was among his most important students and he considered John Paul II to be one of the greatest Polish heroes.

It is difficult to overlook the controversial themes of Szukalski’s life. His writings reveal evident anti-Semitic and anti-Christian undertones and fascination with Italian totalism. On the other hand, Norbert Strassberg – the son of a Jewish tailor from Lvov – was among his most important students and he considered John Paul II to be one of the greatest Polish heroes.

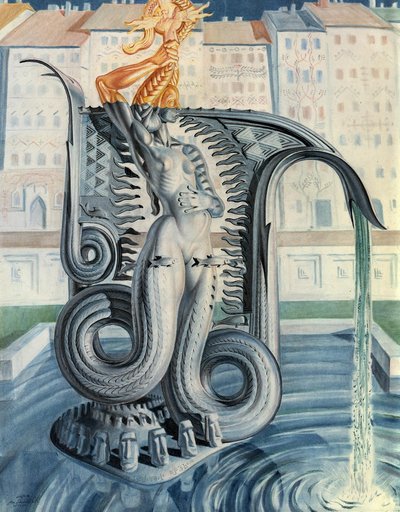

Stanisław Szukalski was a man full of contradictions. The anti-semitic themes of his works were largely testimony to the era, although they were probably also linked to relations with art critics, some of whom were of Jewish origin. But then again, Norbert Strassberg was his most beloved disciple. Szukalski personally visited Strassberg’s father in the Jewish quarter to ask permission for his son to join Szczep Rogate Serce (‘Horned Heart Tribe’), his artistic group. In turn, although he was critical of the work of the Catholic Church, he was extremely enthusiastic about John Paul II, to whom he even wrote a letter offering to carve a monument in his honour. Such a monument obviously was not – and could not – be created, his idea for the project was for the Holy Father to crush the head of a completely naked devilish hydra, covered with scales, with a peasants' flail in his hands ...

Not many people know that one American pupil of Szukalski was Leonardo DiCaprio, who, while preparing for the role in the Titanic was inspired by the artistic rebellion of his adopted "grandfather".

Whilst residing in California, Szukalski was a neighbour of George DiCaprio, Leonardo's father. And since both were artistically inclined, the latter drawing comics, the two men became friends, often visiting each other. Hence the close relations with Leonardo DiCaprio, who, together with his father - after the death of Stach from Warta - sponsored an exhibition of his works. Did this knowledge actually influence the shape of James Cameron's film – that’s hard to say.

Whilst residing in California, Szukalski was a neighbour of George DiCaprio, Leonardo's father. And since both were artistically inclined, the latter drawing comics, the two men became friends, often visiting each other. Hence the close relations with Leonardo DiCaprio, who, together with his father - after the death of Stach from Warta - sponsored an exhibition of his works. Did this knowledge actually influence the shape of James Cameron's film – that’s hard to say.

What remains today after Stanisław Szukalski? What is the significance of his legacy?

Stach of the Warta is increasingly better known, in Poland and in the world, but our attitude towards him is homogeneous. I think once a big exhibition in Krakow or Warsaw is organised, we will start talking about him differently, because he certainly deserves it. If we reject certain silly things, of which there are a few in his artistic views, then we will find many important and significant statements not only about art and its role in human life but also, for example, the need to unite Europe. He was an interesting and exciting creator; undoubtedly a bit crazy but also an incredibly inspirational visionary, a character that deserves to be called an Artist with a big "A".

Poland.pl

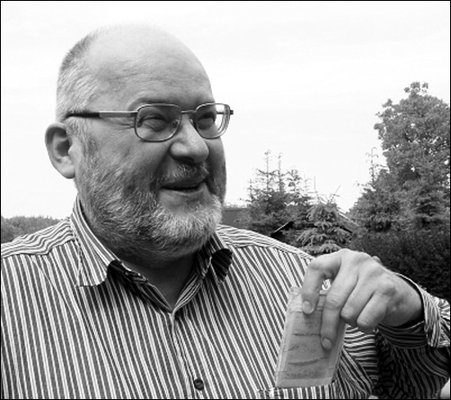

LECHOSŁAW LAMEŃSKI - art historian and critic, professor since 1974, employee of the Institute of Art History of the Catholic University of Lublin, head of the Department of the History of Modern and Contemporary Art of the Catholic University of Lublin, 1999-2005 the director of the Institute between 1995-2005. Contributor to the literary and artistic quarterly "Akcent" (editor of the department of visual arts and art history), president of the Lubelski Branch of the Association of Art Historians.

He primarily deals with Polish art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially sculpture and architecture. He is the author of the following books: Tomasz Oskar Sosnowski 1810-1886. Rzeźbiarz polski w Rzymie (‘Tomasz Oskar Sosnowski 1810-1886. Polish Sculptor in Rome’, 1997), Stach z Warty Szukalski i Szczep Rogate Serce (‘Stach from Warta Szukalski & Horned Heart Tribe’, 2007), Moi artyści, moje galerie. Teksty o sztuce XIX i XX wieku (‘My Artists, My Galleries. Texts about 19th & 20th Century Art’, 2008), Bibliografia historii sztuki dawnego województwa lubelskiego za lata 1965-2000 (‘Bibliography of the History of the Art of the Former Lublin Province in 1965-2000’, 2008), and Zatrzymani w kadrze. Eseje o współczesnych artystach lubelskich (‘Detained in the Cadre. Essays on Contemporary Lublin Artists’, 2016), as well as more than 300 essays, articles, reviews, bibliographies and introductions to exhibition catalogues and dozens of entries to the Catholic Encyclopedia. His texts have appeared in publications such as “Znak", "Tygodnik Powszechny", "Art & Business" and "Biuletyn Historii Sztuki".

19.05.2017