Polish cinema according to Andrzej Wajda

Andrzej Wajda, winner of an Oscar for lifetime achievement, talks to Polska.pl about a new golden era of Polish film, the birth of Solidarity portrayed in Man of Iron and the phenomenon of the Polish film school.

Magdalena Majewska, Polska.pl: Which film do you consider the most important, and which the best one in your career?

Andrzej Wajda*: Ashes and Diamonds (1958) describing how we relate to WW2 still seems the most important film to me, since it gave a new opening for the Polish film school; it was a new voice. And as far as my best film is concerned, I would say without a moment’s thought Man of Marble shot in 1976. Never in my whole long life have I had such an interesting and original screenplay at my disposal. Its author, Aleksander Ścibor-Rylski, very successfully combined two themes: a Stakhanovite worker from the 1950s and a girl, played superbly by Krystyna Janda, who wants to make a film about him in the 1970s. So the 1950s which she brings to the screen seem a distant past for her. And here lies the strength of this film—it shows the reality of the 1950s through the eyes of a young girl who lives in the 1970s. There is something in this film that is absent from other films of this kind in socialist states, namely that a Stakhanovite bricklayer from the 1950s speaks in his own voice on behalf of the working class. In reality, it was the workers’ and peasants’ party government that spoke for workers and peasants. And here suddenly comes an individual, a worker who speaks his mind addressing the government and says what he thinks about its actions. It had never happened before in the cinema of the Eastern bloc countries. Political transition in Poland after 1970, following the tragic developments on the coast, made it possible to shoot this film. I had been waiting 13 years to make Man of Marble until Edward Gierek came to power together with other politicians, including Józef Tejchman, who made my project possible.

Was there any film that you wanted to make but missed out on? Which unrealised project do you regret the most?

I made a few dozen films and each one involved three or four projects that were not carried out, for various reasons. Some for political reasons: they weren’t shot at an opportune moment. There were projects I abandoned because they didn’t go the way I wanted. Or the ones for which the time wouldn’t be ripe from the audience’s perspective. In the case of The Promised Land I was absolutely sure the audience was ready to absorb it since Poland of the 1990s was shrouded in grey and The Promised Land shows the infinite potential of success. You will have ups and downs along the way but your initiative is what counts. I was amused when after I finished making the film, around half a year later, I found myself in Paris together with Wojciech Pszoniak, Daniel Olbrychski and Andrzej Seweryn (who played the three main characters – ed. note). They were already looking for their place in EUROPE. Daniel got engaged in projects by Claude Lelouch, Andrzej was learning French intensively to work in the Comédie-Française as a French actor, and Wojciech Pszoniak was looking for a job in a theatre and eventually arranged several interesting theatrical events in France. The film’s message influenced the lives of actors who created it.

It’s a film in a truly American style...

Yes, but when the film was entered for Oscars in 1975, its American spirit was of no use because it was judged to be anti-Semitic. That was why, after it was bought by an American distributor, the film has not been shown in the United States until today. It is one of my most painful experiences because I thought that The Promised Land is a truly American production with its message and topic despite being produced in Europe.

What were the beginnings of the Polish film school acclaimed worldwide?

Polish film from the very beginning, since 1945, was created by filmmakers themselves. The film studio “Czołówka” (Opening Credits) of the Polish Army was established in 1945. Those were our older friends who already before WW2 laid the foundations for an ambitious and artistic cinema. They used to theorise about that cinema more than they could practise it, and here new possibilities opened up. Despite all censorship restrictions and difficulties, Polish cinema emerged right after WW2 because Wanda Jakubowska shot The Last Stage. Nobody had ever seen Oswiecim on the screen even though everybody knew about this Nazi concentration camp. Aleksander Ford made Border Street – everybody knew about the ghetto and the Warsaw ghetto uprising. But the reality was shown only in the film. I also made Canal. The Warsaw Uprising was a well-known fact but nobody had seen the canal scenes. And those three movies proved that we made films not only for the Polish audience, that we had stories that could capture the world’s interest. And they dealt with the war the way we had lived through it. Later on, many films by Andrzej Munk and other friends from the Polish film industry drew on this very subject.

And what is the condition of this cinema today?

Cinema after 1989, moving from state ownership as it was in the Polish People’s Republic to complete liberty from any financial or topical restrictions, that is to freedom together with our country which had finally won it, must have obviously found itself in a completely new situation. Definitely the situation was very difficult because the first films from the West, much awaited by the audience, especially the American ones, started to cross our borders. So the cinemas were offering foreign productions. At that time, we as the Polish Filmmakers Association thought we were responsible for the Polish film industry. We set up the Committee for the Protection of Cinematography. We got to understand very quickly that without a new law on cinematography just like those that the Western countries had, especially France, there was nothing we could do. The moment the law entered into force over 10 years ago the commercialization idea did not spread over the whole Polish film industry. It made it possible for the Polish Film Institute to provide initial funding for a film to be made, that is for the screenplay and realisation of the film concept. Then it’s the directors that initiate a film venture and not the producers. They create drafts of films they would like to make and only then the project in question is handed over to the producer. So there was far greater potential for quality films and debuts to be produced. They were interesting enough to win many awards at international festivals. Polish cinema again returned to Europe and even further as evidenced by the Oscar for Ida, Paweł Pawlikowski’s great film.

Moreover, first attempts have been made to improve films’ distribution since the number of cinemas has decreased in comparison with times of the Polish People’s Republic when we had 3,000 permanent cinemas. It turns out that they were located in districts where it’s more profitable now to open a restaurant, a shopping mall or build a hotel. There is this great initiative I support – a cinema around the corner. It involves small cinemas for several dozen people where you can watch films. Those cinemas have no service personnel who add to the cost of film distribution. The films are transferred electronically to a group of viewers who watch them together. I’m sure that the film isn’t meant to be watched alone because there is no spirit of interest, joint laughter or dislike among the audience. And these lead to building a genuine relation between a director, a film and an audience. We are on the right track. Importantly, such cinemas emerge in small towns.

Polish documentaries are playing an increasingly important role in all of that. I was very much impressed with Casa Blanca by Aleksandra Maciuszek. The film is set in Havana and tells a story of a 70-year-old mother and her son who has Down syndrome. The second very moving picture is titled Call me Marianna by Karolina Bielawska about a person who wants to change sex. And there is also Joanna by Aneta Kopacz about a relationship between a mother dying of cancer and her son. Those films are a kind of a lodestar for feature films and an answer to the question where to find a new hero. We haven’t seen such characters in Polish film until recently.

At the meeting presenting Joanna by Aneta Kopacz you said that documentaries are somehow ahead of feature films because their topics cannot be entirely translated into dialogues.

There is no such actor that could play the role of Call me Marianna’s main character. It must be a person talking to the camera with his/her own voice and showing what he/she really wants regardless of what our society thinks. An actor wouldn’t manage to render it. Such characters show how remote we are from understanding a world which opens to the freedom of individuals.

Oscar-nominated Joanna was made under the guidance of the Wajda School staff. What sets it apart from other film schools in Poland and abroad?

Our school, run by the director Wojciech Marczewski, filled the void that was left by film groups. They were places to discuss would-be films, concepts, scripts, dialogue lines. Whether I was on Jerzy Kawalerowicz’s or Jerzy Bosak’s team, I was always among friends, who—even when they had critical comments on a film—would always do that disinterestedly, but the atmosphere surrounding those groups has not survived until today. That’s why I reckoned it might be worthwhile to set up a school after the school. Film school graduates come to us and they face the toughest task: how to make a first film? They have no one to talk about such a film, no one to ask for advice. We have such experienced film directors who teach at our school as Wojciech Marczewski, Agnieszka Holland, Jacek Bławut, Volker Schloendorf, and Aleksandr Sokurov. We also have Ida’s director, Paweł Pawlikowski. We help write the scenario and work on the concept of the future film. But that’s not all—we can enable the director to shoot scenes from a film he will be making. He then will be able to show them to a producer and those he wants to get to collaborate with on the film. He will be able to show them his work, instead of just talking about how the film will look like. We run a number of courses. One of them is dedicated to young Polish directors. The other is called the “Screen.” It’s an international training programme for film professionals. It brings together directors from Europe and from around the world to prepare their first movie over a one-year time span. It offers them space to discuss (in English) films they find interesting. If Polish cinema were not growing, the school wouldn’t stand a chance of prospering, either. The school was set up around ten years ago when our cinema found a new lease of life.

We also have a group that deals with documentaries, and it’s run by Marcel Łoziński, a superb director with extensive experience. It saw the birth of a few award-winning films, such as Joanna, which was made under the supervision of Marcel Łoziński, and it has new ones in the making.

Finally, there’s also the “kindergarten,” where a group of secondary school students encounter professional cinema and realise their film ideas.

We also have a course for creative producers, so that they could contribute artistically to the films they produce, instead of just managing finances and doing business estimates. I mean, they have to do that to bring the film to the cinemas, but the most important thing is that the producer supports the director in his effort to make an original picture, unlike any other, one that would stand out from the thousands of films made every year.

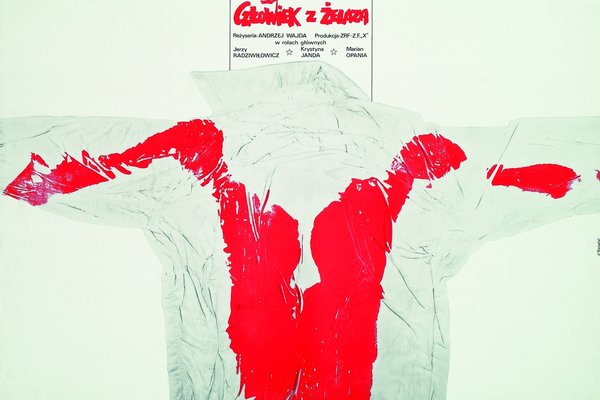

One such original film is your Man of Iron from 1981. It’s unique in that it captures history in the making and portrays it outright.

Yes. Such coincidence seldom happens, and that’s because when new social trends start to appear, it’s very hard to pinpoint them, and even harder to show in films. I must say that the birth of Solidarity [Independent Self-Governing Trade Union “Solidarity”—first legal and independent union organisation in the communist bloc. The establishment of Solidarity on 31 August 1980 gave rise to the transformation of 1989—the overthrow of communism—editor’s note] was so rapid, so dazzling that I understood that it was a film that had be made right away; firstly because I thought Solidarity wouldn’t win at the first attempt. I deeply believed that the communist authorities will curb future democratisation announced by Solidarity and that’s what happened. The martial law proclaimed in Poland on 13 December 1981 did exactly that. That made me set about shooting the film right away, but I managed to do so only because those protagonists appeared earlier in Man of Marble and were its continuation. There were cameras turned on at the Shipyard and the Workers ‘80 documentary was being shot [account of the strike and the August negotiations between the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee and the Government Commission—editor’s note.] Workers ’71 by Krzysztof Kieślowski was made earlier. Polish cinema was ready to embrace a political event such as the birth of Solidarity in the Gdansk Shipyard.

Is it true that shipyard workers themselves helped you in making this film?

Absolutely. They helped me in a number of ways. The film was conceived, as it were, at their request. When I got to the shipyard during the August 1980 strike, it was one of the workers, who was wearing a white and red armband and led me to the negotiation room, said to me: “Please make a film about us.” “What kind of film can I make about you?” I replied. And he says: “Make a film called Man of Iron.” So I made that film to order of a single shipyard worker and I’m happy about that. How did the shipyard workers help us in shooting the film? They told us what the events really looked like before Solidarity was born. For example, Jerzy Borowczak was one of those that started the strike at the shipyard. He put up first posters. He was standing at the one end of the camera, and the camera was facing Jerzy Radziwiłowicz [actor who played the worker]. He was recounting how it happened that he came running to the shipyard, who drew the posters, how he stuck those posters up. As soon as was done talking, I said ‘Camera!’, and Jerzy Radziwiłowicz repeated what he heard and what he remembered. That’s why it came across so lifelike and vivid. Those weren’t memorised lines. That scene depicted a French TV crew that comes and wants to know how it all came about and a worker gives his account of that. That was the most efficient help that I got from the shipyard workers. They told me how Solidarity had been born.

Did the censorship try to interfere in the film? They allegedly wanted to cut 21 scenes, or the exact number of Solidarity’s demands.

Indeed, it was sort of funny. But it turned out that I had the powerful Independent Self-Governing Trade Union “Solidarity” on my side. First, workers from the Gdansk shipyard, then those from Nowa Huta in Krakow, started to send in telegrams to the minister of cinematography in which they demanded that the film should not be censored or cut in any way and that is should be sent to the Cannes festival. That telegram had 16,000 signatures. For the first time in my life I felt that a real force stood behind me and that it would back me up on that film, that I could count on that and so it happened. I didn’t cut either of those 21 fragments, and the film shown at the Cannes festival won the Golden Palm.

How did it go in Cannes? How did the West take the film?

There was astonishment in Cannes that the events had not been fully covered by the press, and there appears a film about them. The Cannes festival is very receptive, maybe the most receptive of all festivals, to the unexpected, fresh, new. You can count on the jury taking interest in such a film and that’s why it won the main award.

From the photographs by Jerzy Kośnik taken of you receiving the Golden Palm I know that the entire film crew walked around Cannes dressed in t-shirts bearing the Man of Iron poster.

Yes, indeed. Even Lech Wałęsa was dressed like that.

You devoted the third film of the series, Wałęsa. Man of Hope, from 2013 to its eponymous character.

I watched Wałęsa from the beginning. When I came over to the Shipyard, the talks with the Government Commission had not yet started. I saw a man who was really aware of a bigger picture. Not in the sense of knowledge, but intuition, seeing with his mind’s eye, like an artist looking at the world. The whole thing could have ended in mere pay rises, money. Of course, the Committee for Social Self-defence KOR played a huge role; the presence of intellectuals: Bronisław Geremek, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Jacek Kuroń, Adam Michnik and others, who understood that only workers could change Polish reality, that no other social group could play such a role. Those workers not only stood up for their wages but for freedom, for the abolishment of censorship. For they didn’t want to make a film or write a novel, but they demanded the abolishment of censorship. What made Solidarity so powerful was that everybody joined in. It was our great common cause. That cause only could win and it did. What I could show, I showed in Man of Marble, but I thought years later that I had some kind of debt to Wałęsa. Especially so as Wałęsa after 1989 was treated extremely meanly and unjustly. After all, politicians are not out there with each season. A politician has a role that no one else can play. Lech Wałęsa played a pivotal role. He understood that any confrontation with the communist authorities at that moment would have led to a bloodbath and harsh repressive measures. That Lech performed that feat in a non-violent way is something without precedent. Obviously, he was surrounded by people who advised him to pursue exactly that course, but there were others who could have persuaded him otherwise. One more thing must be said here: Wałęsa had a bigger following in Europe and worldwide, where everyone wanted to have a labour leader like that. The world looked at Wałęsa as a phenomenon. Which is all the more reason why I should make a film like that: not only to restore him the trust he lost, but also to recall, years after, that such a movement as Solidarity took place in Poland. I thought it had to be done. I’m satisfied that Wałęsa approved of the film.

2016 will mark the 75th anniversary of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s birth. How would you explain the phenomenal popularity of his films worldwide?

The strength of the Polish film school and subsequently Polish cinema was that the Polish People’s Republic was nearest to the Berlin Wall, and everybody was curious to find out what lay behind that wall. News from our country met with interest in Europe. And we were able to say a lot, because we managed to secure the greatest extent of freedom for our films. But those films in the first place were about the war, about our situation in communist Poland. We were trying to open up to the world, which wasn’t easy because of censorship. Kieślowski was a unique Polish director who found bits and pieces in his times that were understandable to the Western audience and people on the other side of the Berlin War. What’s more, his Three Colours showed that he could equally easily tell stories about life there: how people in the West are like, what they strive for and want. Kieślowski had a universal vision of man, which was a gift that not everyone had. Thanks to him, Polish cinema after many years turned to the world again.

Interview by Magdalena Majewska

*Andrzej Wajda – film and theatre director, laureate of the Oscar for lifetime achievement in 2000. His films: Canal and Ashes and Diamonds, which examined the WWII times, brought him international recognition. They also ushered in the so-called Polish film school, a movement that lasted in Polish cinema between 1955 and 1965 and was inspired by Italian neorealism.

He was born in 1926 in Suwalki in eastern Poland. In 1946 he started to study painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow without completing the course. In 1953 he graduated from the Leon Schiller State Theatre and Film School in Lodz.

His Man of Marble from 1976 won him international renown: a film about a young female journalist who discovers a dark past of a forgotten Stakhanovite worker. The picture was hailed as a manifesto of the cinema of moral anxiety which revealed pathologies of the communist system. Its continuation, Man of Iron from 1981, was awarded the Golden Palm at the Cannes festival. The trilogy’s third part, Wałęsa. Man of Hope, was produced in 2013 and is a fictionalised biopic of Solidarity’s leader, Lech Wałęsa.

Wajda received four Oscar nominations, most recently in 2008 for Katyń, which tells a story of the Soviet murder of almost 22,000 Poles, including 10,000 Polish officers, committed in the spring of 1940. Earlier Oscar nominations included: the Young Girls of Wilko, Promised Land and Man of Iron.

Wajda adapted for the screen the majority of Poland’s literary canons, such as Pan Tadeusz, a Romantic epic poem by Adam Mickiewicz; Promised Land by Władysław Reymont and Revenge by Aleksander Fredro.

The director has received numerous awards, among them the Venice Festival’s Golden Lion, the Berlin Festival’s Golden Bear for lifetime achievement, the Cesar Award, the Felix Award, and the Japanese Kyoto Prize.

KK

28.08.2015