Sociological snapshots

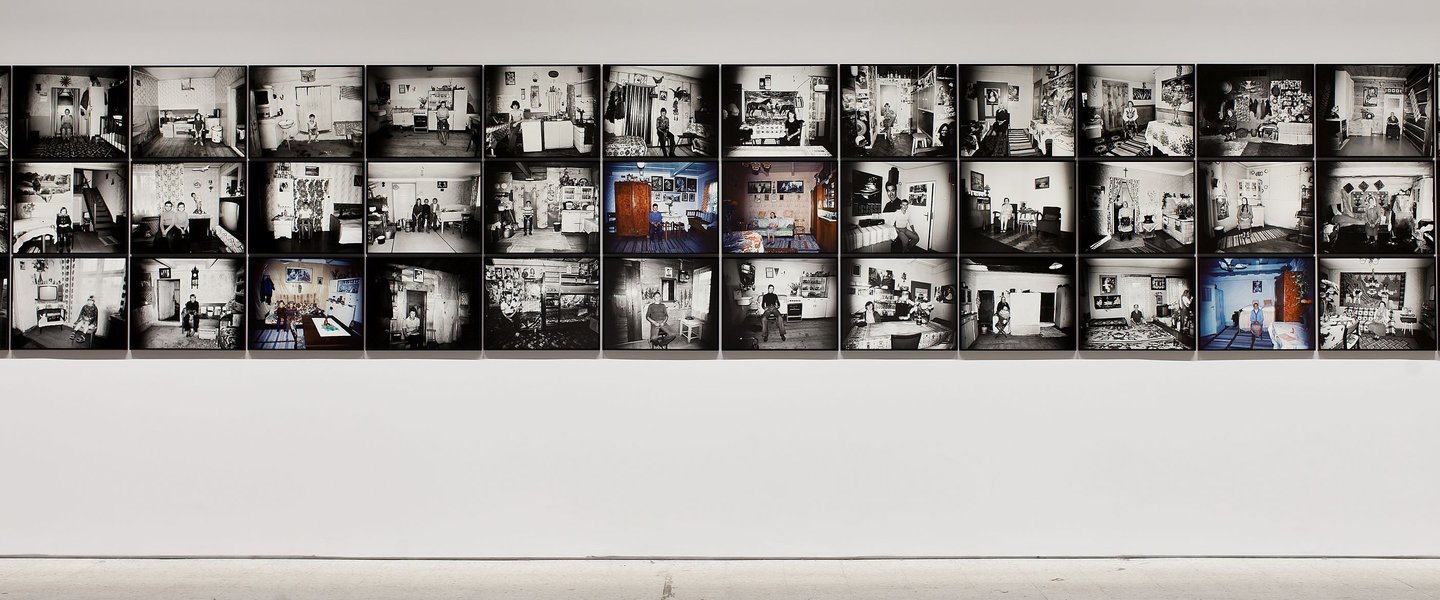

Zofia Rydet’s photographs are unique in the way that they document life in Communist Poland. Over 900 previously unseen photos are now on display at the “Zofia Rydet. Record, 1978-1990” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. Rydet’s photographs can also be found at some of the world’s most prestigious museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

A blacksmith from Wilcze Gardło in Silesia has his right hand planted comfortably in his pocket, while smoking a cigarette with his left hand. Zofia Rydet took a photograph of him in his smithy in 1983, three years after taking a snapshot of a gamekeeper from the Szczecin Voivodeship, who posed for her in an armchair in his own apartment – dressed in a uniform but without a gun. The photograph shows his gun hanging from a tiled stove. Another one of Rydet’s subjects was a woman in a kiosk in Biały Dunajec. Taken in 1984, the photo shows the woman posing with postage stamps behind a counter. In a different photo, a woman selling toasted sandwiches in the Suwalki region had to leave her trailer booth for the photo to be taken, due to space constraints. She stood on the stone threshold wearing a white apron that was popular between 1978-1980, when Rydet took the photo. The latter subjects also posed for Rydet as part of her “Disappearing Professions” series, one of many series that make up her “Sociological Record” collection. Her most famous photos show the interiors of rural cottages that Rydet marched into from the street, taking photos of people in their natural environment – cooking dinner, peeling potatoes, milking cows, putting horseshoes on a horse. She forbade her subjects from smiling, wanting to make the situations she captured as realistic as possible. If those being photographed insisted on smiling, Rydet would tell them that they needed to keep a serious pose as the photos would be shown around the world and would be shown to the Pope. This usually convinced the subjects to follow Rydet’s lead.

A blacksmith from Wilcze Gardło in Silesia has his right hand planted comfortably in his pocket, while smoking a cigarette with his left hand. Zofia Rydet took a photograph of him in his smithy in 1983, three years after taking a snapshot of a gamekeeper from the Szczecin Voivodeship, who posed for her in an armchair in his own apartment – dressed in a uniform but without a gun. The photograph shows his gun hanging from a tiled stove. Another one of Rydet’s subjects was a woman in a kiosk in Biały Dunajec. Taken in 1984, the photo shows the woman posing with postage stamps behind a counter. In a different photo, a woman selling toasted sandwiches in the Suwalki region had to leave her trailer booth for the photo to be taken, due to space constraints. She stood on the stone threshold wearing a white apron that was popular between 1978-1980, when Rydet took the photo. The latter subjects also posed for Rydet as part of her “Disappearing Professions” series, one of many series that make up her “Sociological Record” collection. Her most famous photos show the interiors of rural cottages that Rydet marched into from the street, taking photos of people in their natural environment – cooking dinner, peeling potatoes, milking cows, putting horseshoes on a horse. She forbade her subjects from smiling, wanting to make the situations she captured as realistic as possible. If those being photographed insisted on smiling, Rydet would tell them that they needed to keep a serious pose as the photos would be shown around the world and would be shown to the Pope. This usually convinced the subjects to follow Rydet’s lead.

When entering people’s homes, Rydet would look for “beautiful or unusual objects”, using them as the focal point of subsequent conversations and photographs. Her photos are among the most valuable records of Communist Poland’s last decade. They remain, to this day, unknown to many as the passionate photographer never found time to develop the negatives. The researchers who developed the photographs are only starting to realise the enormous scope of the project.

“Until now, we never knew the full scope of Rydet’s leading masterpiece, “The Sociological Record.” Only a small part of the collection’s 20,000 photos ever saw the light of day. Rydet never found the time to develop the negatives. She felt that she didn’t have much time left and that completing her mission was going to be impossible anyway. After all, it is an impossible feat to photograph every single apartment in Poland, especially given that Rydet had hoped to return to the flats a few years later to document any changes that had been made. Up to now, 200 photographs were on display within the exhibition circuit. The remainder were presented to the public thanks to an alliance between several institutions that came into being over the last three years. These institutions are the Zofia Rydet Foundation, run by her heirs, the Gliwice Museum, the Foundation for Visual Arts, which organises the annual Krakow Photomonth, and the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw,” Sebastian Cichocki, one of the curators of the exhibition, tells Polska.pl.

In her article published in the British newspaper “The Telegraph” at the end of November, Lucy Davies describes Zofia Rydet as “the pensioner who tried to photograph inside every house in Poland.” The article about the famous Polish woman, who took over 20,000 photographs of people in 100 towns and villages, has attracted a very high number of online readers. Persuading her subjects of the global scope of her work, Rydet did not believe that her photos would in fact be shown around the globe and that some of the world’s most famous museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, would exhibit her work.

However, she did sense that her work was of great importance. “When Józef Robakowski asked her in an interview about the significance of “The Sociological Record”, the photographer said that she didn’t know if it counted as art, but the important thing was what would happen to the project in the future. And indeed, with the passing of time her material has in fact gained significance – it has become increasingly relevant, open to interpretation from a fresh angle. In large part due to the knowledge transmitted through these photos. They provide an instrumental source of knowledge on areas such as architecture, industrial design, modernisation of the rural areas, changing trends and even pop culture,” Sebastian Cichocki says. That is why, according to the curators of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Rydet’s work is a canon of Polish art, one which her successors can draw inspiration from. “Alongside her are artists such as Andrzej Wróblewski, the painter, Alina Szapocznikow, the sculptor, as well as the architect Oskar Hansen. These days, many famous photographers seek inspiration in her work and her projects resonate with the younger generation,” Cichocki says.

However, she did sense that her work was of great importance. “When Józef Robakowski asked her in an interview about the significance of “The Sociological Record”, the photographer said that she didn’t know if it counted as art, but the important thing was what would happen to the project in the future. And indeed, with the passing of time her material has in fact gained significance – it has become increasingly relevant, open to interpretation from a fresh angle. In large part due to the knowledge transmitted through these photos. They provide an instrumental source of knowledge on areas such as architecture, industrial design, modernisation of the rural areas, changing trends and even pop culture,” Sebastian Cichocki says. That is why, according to the curators of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Rydet’s work is a canon of Polish art, one which her successors can draw inspiration from. “Alongside her are artists such as Andrzej Wróblewski, the painter, Alina Szapocznikow, the sculptor, as well as the architect Oskar Hansen. These days, many famous photographers seek inspiration in her work and her projects resonate with the younger generation,” Cichocki says.

However, it is not only artists and photographers who are interested in Rydet’s work. Historians and sociologists have also been fascinated by her projects. It is a pity, therefore, that the stories behind so many of Rydet’s photos will remain unknown. Those photos that she did manage to explain, tell us a lot about the state of society and the mood in Poland at the time. For example, the owner of one house in Podhale, in which a picture of the Virgin Mary hangs alongside portraits of Communist politicians Gierek and Brezhnev told Rydet that “I believe in the Holy Mother and I praise her. Gierek and Brezhnev can lick my ass, but they protect me when someone important drops by.”

Rydet only became seriously involved with photography as a forty-year-old. Born in 1911 in Stanisławów, in what is now Western Ukraine, her dream was to one-day study at the Academy of Fine Arts but her parents pushed her to finish her studies at a school for economics for women. After the war she settled first in Kłodzko and later in Bytom, where she ran two shops selling stationary and toys. It was only in 1950 that she returned to her passion of photography. After initially learning the trade independently, she later studied within the framework of the Gliwice Photography Society. In the early 1960s, Rydet moved to Gliwice, where she taught photography at the department of architecture at the Silesian University of Technology.

Rydet only became seriously involved with photography as a forty-year-old. Born in 1911 in Stanisławów, in what is now Western Ukraine, her dream was to one-day study at the Academy of Fine Arts but her parents pushed her to finish her studies at a school for economics for women. After the war she settled first in Kłodzko and later in Bytom, where she ran two shops selling stationary and toys. It was only in 1950 that she returned to her passion of photography. After initially learning the trade independently, she later studied within the framework of the Gliwice Photography Society. In the early 1960s, Rydet moved to Gliwice, where she taught photography at the department of architecture at the Silesian University of Technology.

She first came across socially engaged photography in 1959 when she visited the “The Family of Man” exhibition, in which over 500 photos documented the behaviour and rituals of people from all over the world. This exhibition inspired Rydet’s first high-profile exhibition, “Little Person”, which looked at the daily lives of children. Rydet’s main masterpiece, however, was her “Sociological Record.” It started of as a documentation of Podhale residents in their own homes but soon expanded to several dozen of the 49 voivodeships, including the Lublin and Suwalki Voivodeships as well as other countries – Rydet also took photographs of immigrants in the United States and Lithuania. The “Sociological Record” collection also consists of photographs of artists’ studios and their apartments.

The “Zofia Rydet. Record, 1978-1999” exhibition, co-organised by the Foundation for Visual Arts, is the widest ever collection of photographs from the “Sociological Record”. The exhibition can be visited until 10 January 2016.

KAROLINA KOWALSKA

30.12.2015