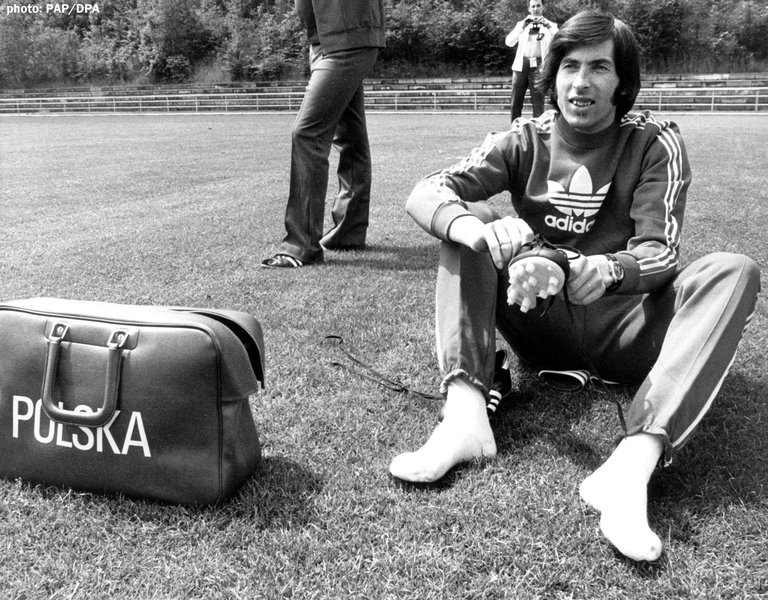

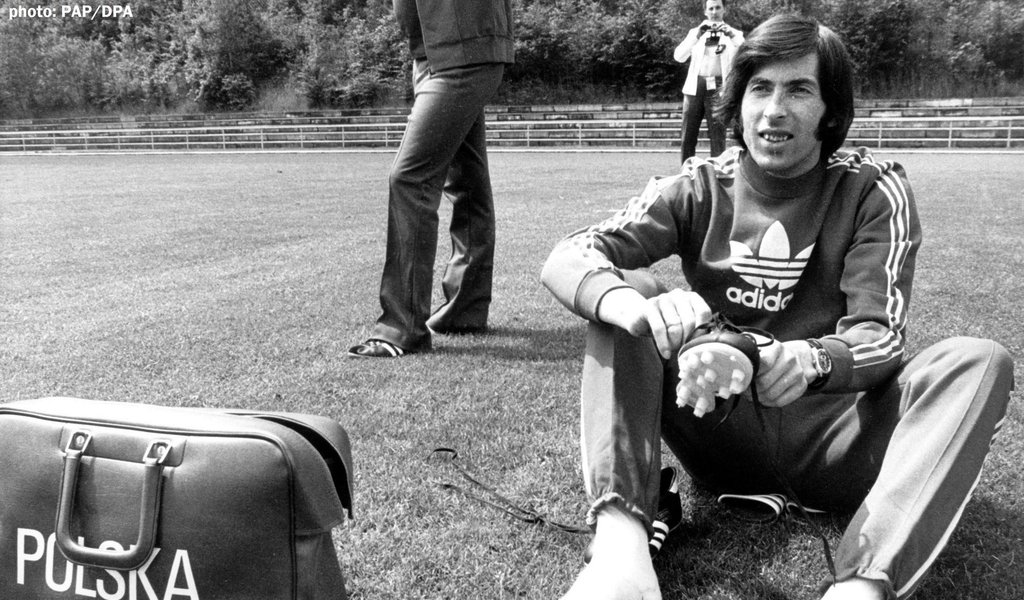

Kazimierz Deyna. If you’re no kamikaze, don’t you touch Kazik!

Without him Poland wouldn’t have won its third place in the World Cup or Legia its major trophies. Loved and booed in his lifetime, he could not cope with his life.

In October 1966, Kazimierz Deyna came to Warsaw. He was 19 but already had a lot of experience. He was the brightest hope of his native Starogard Gdański, Lechia Gdańsk competed with Arka Gdynia to sign him, when he played for ŁKS he would hide from Internal Military Service patrols that hounded him to perform his compulsory military service. It was in Legia that he was to do it.

He was wearing the uniform only for the first month. Then he went on to play for Poland’s top club. He had already learnt the dealings of football officials, the games of politicians, the self-interested behaviour of coaches and teammates. But he had only received secondary education at a basic vocational school of a shoe-making plant in Starogard, while Przegląd Sportowy was his reading staple. It was in the capital that he began to learn what real life looked like. His new friends, the excellent players, made sure about that.

Crescents & ducks

Crescents & ducks

In the late 1960s, Deyna emerged as the biggest revelation at Łazienkowska Street. Legia had failed to win the cup since 1956. Even though they had some very good players, they had to accept the supremacy of Silesian teams. The ambitions of the military and the capital city had to be put off with each season. But from autumn 1966, fans would come to see not only Legia but Deyna specifically, and three years later they finally got what they had been waiting for: the national championship title. Deyna was untouchable, all attempts to foul him triggered the response chanted by the crowds: ”Deyna Kazimierz, if you’re no kamikaze, don’t you touch Kazik!”

For reasons unknown, his teammates would call him Kaka. According to an established line of interpretation, it was after the way he performed his free kicks: “crescents” and “ducks.” The way Deyna did them was unlike anything seen in Poland before. He would send the ball spinning so that it bypassed the wall on either side and landed in the net, in the manner of Brazilian geniuses. His greatness was in his ability to predict what was about to happen on the pitch next. Garry Kasparov was said to be able to anticipate 17 of his opponent’s moves. When you watched Deyna play you might have an impression that the opponent didn’t know yet what to do with the ball and when he did Deyna was already in the right spot. The rivals just seemed to give the ball straight away to him. He wasn’t too fast, he avoided headers, his dribbling style wasn’t exactly South American-like. He was criticised for holding the ball and running around in circles. But he knew what he was doing. A simple country lad, once he was on the pitch he transformed into a master. Before he took a pass, he was already feinting a move, something repeated years later by Zinedine Zidane. That made him a few centimetres and fractions of a second quicker than his opponents. He was 180cm tall but seemed taller by keeping upright. He was running freely with the ball around defenders unbalancing them. He could pass the ball precisely over a few dozen metres, and when he was 20 metres away from the box area defenders were already on alert. From that distance, each shot could put the ball in the back of the net. When I asked him how he did that, he would reply: “It’s simple. Everybody tries to aim at the goalie since he attracts the ball. I aim at the posts. When the ball lands at the wrong side no one is upset. When it goes in near the post they say I’m a genius, which I don’t deny. But my actual accuracy is around 50 per cent.” Only once did he fail to score a penalty in an important match: in a World Cup game against Argentina. “Goodness me, what they will do to him now,” sighed Kazi’s mum watching the match on TV at home in Starogard. Allegedly, someone tried to reach with a stone the windows of the Deynas’ sixth-floor flat at the corner of Emilia Plater and Świętokrzyska Streets. A few months earlier in a qualifying game against Portugal in Chorzow, Deyna scored directly from a corner, almost securing Poland’s going through. But some in the “beautiful Silesian audience,” to borrow Jan Ciszewski’s words, booed the scorer. Only because he was a Legia player. Europe recognised Deyna’s talent faster than the Silesians, who were jealous of their Górnik and Włodzimierz Lubański. By sheer luck, in the 1969/1970 European Champion Clubs’ Cup (predecessor of the Champions League) Legia was drawn to play France’s champions Saint Etienne and beat them twice. Deyna scored two of the three goals. The French sport newspapers "L’Equipe", "France Football", and "Mirroir du Football" were popular across all of Europe, so the word spread of the 22-year-old Polish midfielder. The French press dubbed Deyna the General. Fast forward a few months and the General is playing in the Champion Cup semi-finals, with Legia having qualified into Europe’s top four teams only to lose against the ultimate champion Feyenoord.

Puppet theatre

After the little respected Olympic gold it was only the World Cup qualifiers, which culminated with eliminating England, that made foreign football world rub their eyes in disbelief. After the World Cup, they were wide open. Grzegorz Lato was the top scorer, Robert Gadocha the best left winger, Jan Tomaszewski the best goalkeeper, and Deyna the best playmaker. The Polish side lost the fight for the final against Germany, but won fans’ hearts. The German press wrote about Deyna that he was pulling the strings with Lato, Gadocha, and Szarmach attached, as if in a puppet theatre, while match scenarios were written by coach Kazimierz Górski. But this bliss lasted only five years. After the Munich success, the Polish side started to grow too big for their boots. The sheer honour of donning the jersey with the white eagle was no longer enough. They started to be preoccupied with money and dream about transfers to Western clubs. Such transfers were next to impossible at the time. The fact that in spite of the clear lack of commitment Poland managed to win Olympic silver in Montreal spoke of their footballing skills. But the second place was considered a failure at home and manager Kazimierz Górski was sent off. His successor Jacek Gmoch tried to pick up the pieces, only with partial success. At the World Cup in Argentina the Polish side was among the teams ranked 5th-8th. Edward Gierek sent them a congratulatory telegram, yet another sign of the propaganda of success. But we had hoped for more. An era was coming to an end and a new generation came knocking. Deyna’s days in the squad were counted.

Boniek breathing down his neck

Boniek breathing down his neck

A symbolic change came with Zbigniew Boniek’s taking over the role of Kazimierz Deyna. When Włodzimierz Lubański sustained injury in the game against England and it was certain he wouldn’t return to the team any time soon a new captain was needed. It all happened aboard a plane carrying the squad for a tour of North America. Deyna was the best player but he wasn’t much of a talker, while the skipper role called for a more articulate lad that would be focused on the team, not only himself. The team voted for Lesław Ćmikiewicz, but then Kazi opens his mouth: “Hang on a second, but I’m next in line after Włodek.” The mates went silent, Kazimierz Górski just nodded, and that stuck. Deyna captained the team in two World Cups, in 57 matches altogether. That was a record. His position was challenged only by the angry young Zbigniew Boniek, 22 years old at the time, during the World Cup in Argentina. Boniek’s star was just beginning to shine, while Deyna’s career was slowly coming to an end. The young man was impatient and they had a heated squabble at a ping-pong table. Later on, when Deyna was to take a penalty against Argentine, Boniek asked him if he would withstand the pressure and if he wanted to be replaced. In such a situation, Deyna could not show weakness. He walked up to the spot but hit the goalkeeper. Four years later, it was Boniek who was the boss in the team. They were altogether different characters. Deyna – quiet, calm, soft-voiced, but able to get his team mates in order with one charismatic glance. Boniek – impulsive, pressurising other players into obedience by shouting. Some simply feared him because he was not only quick to lose his temper but also prone to blows.

A poet, not a hack

In the mid-1970s Deyna enjoyed an international status comparable to that of Frank Lampard, Andrea Pirlo or Xavi in today’s football. Best clubs wanted him but you just couldn’t leave Poland. All the more so as being an officer of the Polish People’s Army, Deyna for ideological reasons could not work for the capitalists or, heavens forbid, in a NATO country. That was at variance with Poland’s raison d’état. Western clubs tried, though, by contacting Legia or him directly. To no avail. He was even deliberately prevented from learning about some offers that came in for him. Real Madrid, AC Milan, Inter, AS Monaco (prince Rainier loved Deyna) — all signalled their interest. Two months after the Argentinian World Cup, Deyna together with Boniek and Grzegorz Lato was invited to the All-World Team for a game against Cosmos in New York. Cosmos was the richest club at the time. After the game, Pele with the club’s Turkish owner made the Pole an offer: Listen, we got a bunch of decent boys here. Cruyff with Chinaglia at the front; you, Beckenbauer, and Rivelino at midfield. What do you say? Deyna couldn’t agree because he had been already in talks with Manchester City, to which he transferred in autumn 1978 for 100,000 pounds. He could not have chosen worse. When I paid him a visit there several months later, he complained that the English didn’t get his intentions and that the half-witted coach put him on as centre forward, exposing him to the risk of injuries in confrontations with big, brutal defenders. But Deyna was a poet of football, not a hack.

Acting for Huston

He started to drink and had his driving licence revoked by the police for the first time. Then the situation repeated itself. Manager Ted Miodoński arranged his transfer to San Diego Sockers, a club in the American league which is a safe harbour for players with their best years behind them. He was still a star there but big-time football hardly paid any notice. So there he was going downhill all the way, all the more so because Miodoński sucked his bank account dry. Years later, Deyna’s wife won a suit against the manager but she didn’t get their money back as Miodoński had gone bankrupt. They lost over a million dollars. During his stay in the US Deyna was increasingly hitting the bottle and not getting on with his family. He found refuge from the problems in coaching kids and playing for an old boys team called the Legends, which provided a source of additional, yet meagre, income. He didn’t know what to do with his life, even though the American football federation allegedly offered him the role of football ambassador during the World Cup in the US. He played a silent part in John Huston’s Escape to Victory, alongside Michael Caine, Max von Sydow, Sylvester Stallone and the footballers Pele and Bobby Moore. He didn’t want to go back to Poland because he was ashamed that he had made no fortune after ten years in the West. He only came over to meet the Polish team during the World Cup in Mexico, and played with them for the last time at a veterans tournament in Denmark in July 1989.

50 cents in the pocket

50 cents in the pocket

Two months later, he was already dead. He was killed on the night of 1 September on a motorway near San Diego. The 15-year old Dogde Colt he was driving crashed into a lorry parked on the shoulder. The driver probably fell asleep. Blood samples revealed the presence of alcohol. Deyna was going home after a training session with youngsters. He had 22 balls in the car. The pocket of his jeans worn without nothing underneath was hiding 50 cents. The injuries were so massive that he was identified by a signet ring and a driving licence, which he had untypically on him, and he was buried with his head bandaged up. His wife Mariola, from whom he had been separated for a few weeks before, arranged for him to be buried in San Diego. She informed the family back at home, the Polish Football Association, Robert Gadocha, who was living in Chicago, and Grzegorz Lato in Toronto. Nobody came. They probably couldn’t make it. In June 2012, an urn with the ashes of Kazimierz Deyna was buried at the Military Section of Powązki Cemetery.

Author: Stefan Szczepłek

Source: "Rzeczpospolita"

KAZIMIERZ DEYNA

- 97 appearances for the Polish national team, 41 goals

- Played in two World Cups (1974, with third place, and 1978)

- Olympic champion (1972, Munich, top scorer award)

- Silver Olympic champion (1976, Montreal)

- Poland’s two-time champion (1969, 1970)

- US three-time indoor champion

- Third in "France Football" poll for the best European player in 1974

- Played for Włókniarz Starogard Gdański (1960-1966), ŁKS Łódź (1966), Legia Warszawa (1966-1978), Manchester City (1978-1981), San Diego Sockers (1981-1987), and San Diego Legends

29.06.2018