11 Facts on 11.11

In just four years, the Great War “changed the skin of the world.” Previously thought impossible — Poland’s independence — became reality after 123 years of partitions. 11 November, 11.11, marks National Independence Day. What do you need to know about it? Here are 11 facts about 11.11 for the centenary of Independent Poland!

1. 10 November

In the morning of 10 November, Commandant Józef Piłsudski gets off a special train from Berlin arriving at the Vilnius Station in Warsaw. He is returning home after 16 months’ prison in the Magdeburg Fortress. The legend of the fight for Polish independence was welcomed at the platform by representatives of the Regency Council (the supreme body of the Kingdom of Poland established by German and Austro-Hungarian authorities in 1917), the commandant in chief of the Polish Military Organisation, and officers. This very day, delegations from various communities were queuing to see Commandant Piłsudski. Just before his lunch, Piłsudski received as many as 23 of them. In the afternoon, the commandant paid a visit to his life partner Aleksandra Szczerbińska and for the first time saw their 9-month old daughter Wanda. The Regency Council held a meeting at 4:30 p.m. in the Archbishops’ Palace at Miodowa street in Warsaw, which made a decision to hand power to Piłsudski over the forming army and entrust him with the mission of forming a government.

2. 11 November

The decision was announced the following day, after a stormy night during which the commandant received representatives of the German Soldiers’ Council, which was in command of the German garrison in Warsaw. Under the agreement, the army was to give up their equipment, including weapons and ammunition, in exchange for guaranteed safe return. Throughout the night, Polish troops and scouts spontaneously took to demilitarising the Germans.

Interestingly, no further ground-breaking events happened in Poland on this day. Piłsudski assumed the function of commander-in-chief of the Polish army on the next day, and announced universal voluntary enlistment into the army, to which 100,000 volunteers responded within a month. The Regency Council was officially disbanded on 14 November — it was also then when the commandant asked Jędrzej Moraczewski to form a government. On 22 November, the latter issued a decree on the supreme representation authority of the Republic of Poland, under which Piłsudski became provisional Chief of State.

Why 11 November then? The date was originally celebrated by the legionnaires, particularly from the pro-French faction, who were part of the commander-in-chief’s innermost circle. The choice of date was decided by the fact that an armistice was signed on that day in Compiègne, ultimately sealing Germany’s defeat. A number of countries, including France and the Commonwealth, celebrate the date to this day.

Why 11 November then? The date was originally celebrated by the legionnaires, particularly from the pro-French faction, who were part of the commander-in-chief’s innermost circle. The choice of date was decided by the fact that an armistice was signed on that day in Compiègne, ultimately sealing Germany’s defeat. A number of countries, including France and the Commonwealth, celebrate the date to this day.

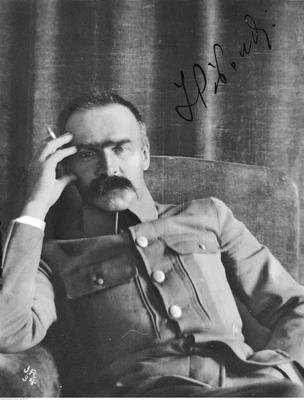

3. Józef Piłsudski

Freedom fighter, martyr of the national cause, Siberian exile, prisoner of the Tsar and the Chancellor, co-founder of the Polish Socialist Party, commandant of the Legions… A legend who was and continues to be the symbol of Poland rising from the ashes. Released in November 1918, he returned home, where from 1922 he was the Chief of State and the supreme commander of the Polish army, among others during the Polish-Soviet war. In May 1926, Piłsudski led an armed coup d’état and took power in Poland, which he ruled until his death in 1935.

He also went down in Poland’s history as a sharp-witted commentator who never spared his adversaries neither harsh words nor his quips.

Here are some of the Marshall’s witticisms:

On means to an end:

“It’s no use banging your head against a brick wall but if other methods have failed you should give this one a try.”

On sometimes difficult relations with his country:

“Even though I sometimes speak about the stupid Poland, call Poland and Poles different names, at the end of the day, it’s only Poland that I serve.”

On the unexpected independence:

“Out of the blue, we have Poland on the first.”

On winning:

“To be defeated and not submit is victory; to be victorious and rest on one’s laurels is defeat.”

On heroes:

“Everyone can cite Kościuszko, bring up his name, admire him and sympathise with his ideals — with impunity and with no consequences or costs. Because Kościuszko is dead. People who sympathise with me must pay with their effort, ordeal, hardship, sacrificed freedom, sacrificed life. Some day when I’m already gone I will also have millions of equally passionate fans who risk nothing.”

A joke to a seriously injured soldier:

“Why are you screaming… What, your leg? That guy over there had his head blown off and he’s not screaming and you, it’s just a scratch.”

4. Fathers of Independence

Restoring the state after 123 years of captivity was not only a breakthrough but a challenge which various circles sought to address. Today, six “Independence Fathers” are regarded as the leaders of this process: Ignacy Daszyński, Roman Dmowski, Wojciech Korfanty, Ignacy Paderewski, Józef Piłsudski, and Wincenty Witos. Representing diverse political views and social and religious backgrounds, they were able to rally around the common cause.

5. The cable

On 16 November, the commander-in-chief of the Polish army signed a cable that notified “the Governments and nations of belligerent and neutral states of the establishment of the Independent Polish State, incorporating all united territories of Poland.” It was broadcast a few days later from the WAR radio station at the Warsaw Citadel, retaken from the Germans. It is worth mentioning that “Poland” was an unfamiliar notion for many — Poland had been just missing from most world maps for 123 years. The telegram was sent to the authorities in France, the USA, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, and Italy.

Later on, the radio station played a very important role during the Battle of Warsaw in 1920. It beamed fragments of the Bible in Morse to jam radio communications of the Red Army.

6. Point 13

On 8 January 1918, US President Thomas Woodrow Wilson in his address to Congress outlined a peace programme that laid the foundations for establishing a lasting and just world order after the Allies’ victory in the First World War. The programme went down in history as Wilson’s 14 points and formed the basis for the armistice signed on 11 November 1918 in Compiègne, which ended WWI hostilities. Point 13 provided for the establishment of an independent Polish state with free access to the sea. In accordance with the plan’s tenets, the restored, politically and economically independent Polish Republic should be erected in “the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations,” and its territorial integrity “should be guaranteed by international covenant.”

In 1918, the victorious states unanimously supported the need for the existence of an independent Polish state.

7. The map

7. The map

For 123 years of being under foreign rule, Poland was not on the map. In 1918, its territory was just starting to form, and the return to borders from 1772 was much hoped for.

The end of the war meant the beginning of uniting the lands of the Second Polish Republic, a process marked by fresh fighting. In December 1918, the Wielkopolska Uprising broke out — the Poles there demanded that the lands under the Prussian rule should be annexed to the nascent state. In line with the provisions of the Versailles Treaty, plebiscites were held in some provinces: in Warmia-Masuria and Silesia. Silesia saw armed struggle in reaction to German repressions against Polish people until 1922 when Polish troops crossed the border and ultimately took over administrative control of the area. There was a conflict festering with Czechoslovakia over Cieszyn Silesia. The eastern border was an open issue, which led to the outbreak of the Polish-Soviet war and the famous Miracle at the Vistula River. The battle, fought from 12 to 25 August 1920 during the Polish-Soviet War, was won by Poland and is considered a major milestone in world history. It not only ensured the Polish independence, but also prevented communism and Soviet totalitarianism from spreading all over Europe.

On the map you can see how the borders of the young state evolved.

8. Poland A + Poland B = Poland

Civilizational progress in the fast-paced 19th century was uneven across the three partitioned lands — the restored state was facing a number of both external and internal challenges. For 123 years, Poland’s territories had been carved up between the three neighbouring powers. They differed in nearly everything: official languages, dominant religions, currencies, legal systems, education systems, disproportions in industrial development, and even patterns of railway tracks. The new authorities had to address these issues, that is why the integration of the so-called Poland A territories, or more developed lands under the former Prussian partition, and Poland B, under the former Russian and Austrian partitions, was one of the major goals of successive governments in 1918-1939.

9. 8 hours

One of the more innovative achievements of the government formed by Piłsudski and led by Jędrzej Moraczewski was the introduction of an eight-hour working day in industry, commerce, and trade. It was still a novelty at that time in Europe. In addition, trade unions and the right to strike were legalised, and health insurance was implemented. It is stressed that the Moraczewski government established political and civic equality for all citizens,  irrespective of their origin, faith or nationality. The citizens could enjoy freedom of conscience, speech, the press, and assembly, and children had access to free universal schooling.

irrespective of their origin, faith or nationality. The citizens could enjoy freedom of conscience, speech, the press, and assembly, and children had access to free universal schooling.

10. Women to the polls!

This atmosphere also made the political empowerment of women possible. A hundred years ago, Polish women were one of the first in Europe to receive suffrage. Interestingly, they were first granted to them by the interim government of Ignacy Daszyński, appointed on 7 November. Ultimately, the right of women to vote and stand in elections was established by a decree of Provisional Chief of State Józef Piłsudski of 28 November 1918. The new law stated that “any citizen of the State irrespective of sex is a voter in elections to the Sejm” and that “all citizens who have the active electoral right are eligible for election to the Sejm.” The first female members of the Sejm were Gabriela Balicka, Jadwiga Dziubińska, Irena Kosmowska, Maria Moczydłowska, Zofia Moraczewska, Anna Piasecka, Zofia Sokolnicka, and Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa — eight highly educated representatives of different political camps. Historians point out that women’s rights were widely accepted in the young Polish state, which reflected, among other things, a common respect for the contribution of women in the long way to the country’s liberation.

11. 11 November revisited

11 November is a symbolic date. In those days, as Piłsudski recalled years later, Poland “was coming into being.”

11 November did not become a national holiday right away. Disputes about an accepted date for the restoration of the Polish state were going on throughout the 20 years of the interwar period, and 11 November was declared a national holiday close to 20 years after these events, in April 1937.

After the end of World War II and the consolidation of the Polish People’s Republic authorities, the holiday was abolished but people have not forgotten. 11 November was an opportunity to demonstrate opposition to the communist system. The first time that the authorities bent to public pressure was on 11 November 1981, by laying wreaths at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Warsaw and entering the date in the calendar of official anniversaries. However, the thaw did not last long and successive demonstrations would be dispersed by the communist police. In 1989, 11 November was again elevated to the status of public holiday. It is celebrated each year as National Independence Day.

Poland.pl

09.11.2018