PL First to Break Free [TIMELINE]

“Dear viewers, on 4 June 1989 the communism in Poland came to an end,” said Joanna Szczepkowska, an actress, on Polish TV prime time news after the June elections. The first partially free elections triggered the collapse of the system not only in Poland but also in the whole Eastern Bloc. What was the path that led to the elections like? Let’s go back to the key moments of 1989!

18 January

After a two-day long discussion and despite opposition from some of the members, the 10th Plenary Session of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR) agreed to trade union pluralism, which allows the “Solidarity” to regain its legal status, since trade unions and country-wide organisations were made illegal under an act of 1982. Even though the “Solidarity” ban sparked massive protests both in Poland and abroad, they did not result in the withdrawal of the oppressive law until 1989.

6 February

The Round Table sessions start in the Namiestnikowski Palace (today the Presidential Palace) as 57 participants sit down, representatives of both the government and opposition. After a plenary session, the talks continue in three working groups called “small tables”, which are given the task of working out mutually acceptable rules of social pluralism and economic reform.

5 April

Two months later the Round Table sessions end. The parties sign an agreement to legalise the “Solidarity” and hold partially free elections. The Position on Political Reforms reads: “The freedom of elections to the Sejm of 10th term shall be limited by the distribution of seats as agreed at the Round Table. […] Non-party candidates, proposed by independent citizen groups, shall contend for a total of 35% of the general number of seats.”

7 April

The Sejm of the Polish People’s Republic adopts constitutional amendments to introduce the chamber of Senate and the office of president. A new electoral law for both chambers of the Parliament and a law on associations are passed.

17 April

By the decision of the Voivodship Court in Warsaw the Independent Self-governing Trade Union “Solidarity” is registered again.

28 April

28 April

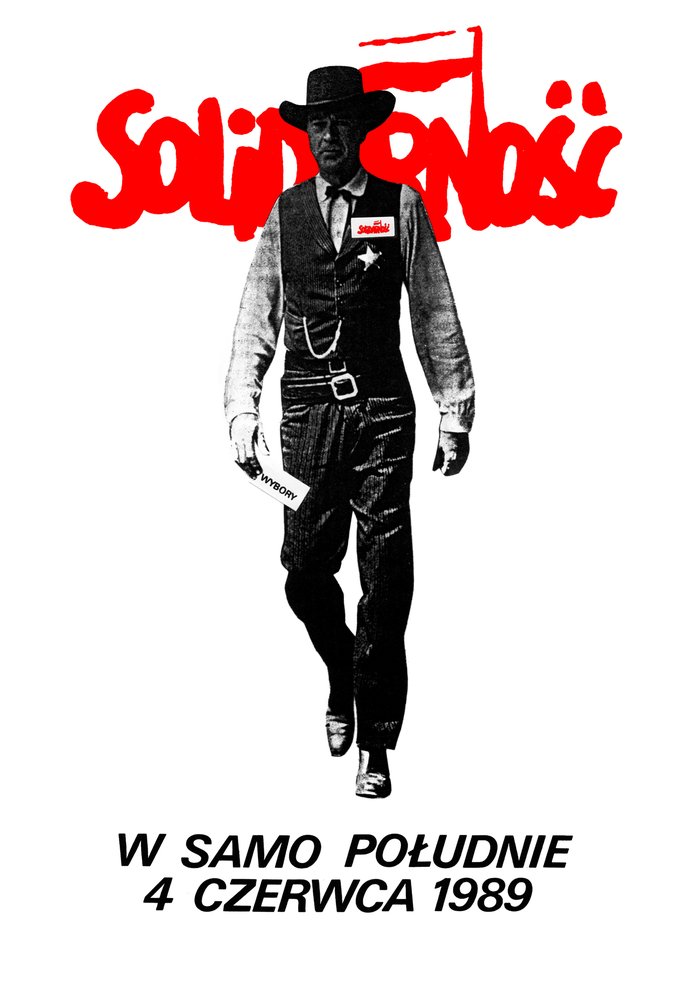

On that day the Polish Radio broadcasts the 1st programme by the “Solidarity” Citizens’ Committee. The parliamentary campaign sets off. The High Noon poster by Tomasz Sarnecki, conceived to increase voter turnout, becomes iconic.

8 May

As decided at the Round Table, the first issue of Gazeta Wyborcza is printed – the 1st independent daily newspaper in Central and Eastern Europe. The issue, with a circulation of 150,000, presents Citizens’ Committee parliamentary candidates.

16-18 May

The Soviet consulate in Krakow witnesses violent demonstrations as the public demands free elections and withdrawal of Soviet troops from Poland. In response, the communist police use water cannons and tear gas. There are over a dozen people wounded in the unrests. A few days later, the refusal to register the Independent Students Association triggers a series of strikes at universities.

4 June

The turnout in the first round of the partially free parliamentary elections was 62% of the registered electors. Much to the government’s surprise, “Solidarity” candidates win 160 seats in the Sejm out of 161 agreed on at the Round Table and 92 out of 100 in the Senate. Prominent Communist Party representatives from the so called general state list do not make it to the parliament. The result is the coming change in the political balance in Poland as well as the whole of Central and Eastern Europe.

18 June

The second round brings the opposition’s repeated success. “Solidarity” wins the last free seats in the Sejm and 7 seats in the Senate, which gives them a majority of 99 to 1.

23 June

A Civic Parliamentary Club, presided over by Bronisław Geremek, is founded in both chambers of the parliament. Despite being a minority under the Round Table agreement, the “Solidarity” opposition is heading for transition from communism to democracy.

Five days later, General Wojciech Jaruzelski admits that the time of PZPR monopoly is over.

19 July

In its first session of the joint chambers of Sejm and Senate, the National Assembly elects General Wojciech Jaruzelski president by a majority of one vote. It is a part of the deal, under which the PZPR representative takes the presidential office and the opposition gets the prime minister’s seat. Earlier, in a conversation with Archbishop Bronisław Dąbrowski, General Czesław Kiszczak warned that if general Jaruzelski is not elected president “we will face further destabilisation and the whole process of political change would have to stop. No other president would earn the respect of the security services and the army.”

24 August

The Sejm accepts the first non-communist prime minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, who headed a coalition government of all parliamentary forces. The Sejm unanimously approves the new government on 12 September. “The final blow was the appointment of a non-communist PM and a coalition government […]. And it turned out that the Soviet Union […] allows it. This impulse triggered the events in other countries, assured them that if there was no intervention in Poland, there will be no intervention elsewhere,” said Ireneusz Sekuła, deputy prime minister, as he stepped down. László Bruszt, a member of Hungarian democratic opposition, said: “The establishment of the government around Mazowiecki is a signal for Eastern Europe that the appointment of the first non-communist PM in the region is possible. Since now, the options include not only political liberalisation or sharing power but also hope for a peaceful change of regime. Until 1989, even in conversations, the only options were to change the model, or rather to make changes to the model. […] Those were extremely important signals for the opposition in this part of Europe and for the citizens as such that it’s only up to the local authorities and that they can achieve the same in their countries.

Poland.pl

The domino effect

Thirty years ago, on 4 June, the first partially free elections in Poland were held, which led to the demise of communism. The domino effect swept across Central and Eastern Europe and the Iron Curtain, which split Europe for nearly half a century, was blown away by the wind of change.

The transition tide travelled from Poland to Hungary, where the representatives of the system, the opposition and the so called third power, that is social organisations loyal to the authorities, sat at a trilateral Round Table to talk about the changes.

In August, about two million citizens of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia made an uninterrupted 600 kilometre long human chain in protest against the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact which took their freedom for 50 years.

Autumn was hot in Germany that year as the process of change culminated in the fall of the Berlin Wall, a symbol of the nation divided since the end of war.

The system also yielded to protesters in Czechoslovakia, which soon split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

The waves of protest also made it to Bulgaria, and in Romania the local dictator, Nicolae Ceauşescu, was shot in the aftermath of the anticommunist revolution.

In the early 1990s, as a result of disintegration of the Eastern Bloc several countries re-emerged on the maps of Europe and Asia. They were: Lithuania, Georgia, Latvia, Estonia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan as well as Russia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro.

03.06.2019

![PL First to Break Free [TIMELINE]](/media/public/56/3d/93d8112457b81e40f5ed7f7ff81.jpg__1440x600_q85_crop-smart_subject_location-400%2C196_subsampling-2.jpg)

![PL First to Break Free [TIMELINE]](/media/public/56/3d/93d8112457b81e40f5ed7f7ff81.jpg__768x600_q85_crop-smart_subject_location-400%2C196_subsampling-2_upscale.jpg)

![PL First to Break Free [TIMELINE]](/media/public/56/3d/93d8112457b81e40f5ed7f7ff81.jpg__1024x600_q85_crop-smart_subject_location-400%2C196_subsampling-2_upscale.jpg)